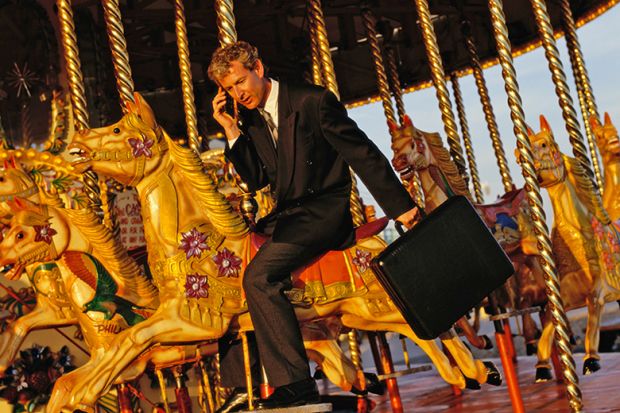

The high rate of turnover of UK university vice-chancellors has been compared to the “managerial merry-go-round” of top football clubs amid warnings that some leadership positions are becoming increasingly unattractive.

Analysis by Times Higher Education has found that more than a quarter of Universities UK members changed vice-chancellors in 2025 or are set to do so in 2026. This intensifies a trend seen in 2024, when about a fifth of the sector made a change.

Of the 38 leadership changeovers, almost half (17) are retiring and a quarter (nine) are moving to lead another UK university.

Richard Watermeyer, professor of higher education at the University of Bristol, said leaders moving from one institution to another could reflect the “limited talent pool” within the UK, as well as top positions becoming increasingly unattractive.

“We just don’t have within the UK system those leaders that are perhaps best positioned to respond to what seem to be pretty intractable challenges that the sector faces.”

Some leaders have now led several institutions. Karen Stanton was promoted to the top job at the University of the Arts London after a spell as interim leader. She had previously been interim vice-chancellor at Lincoln Bishop University, and vice-chancellor of York St John University and Solent University.

“It’s a similar merry-go-round that you see within the top tiers of football with managers being parachuted in in the hope that they provide quick-fix solutions to problems that are incredibly baked in,” added Watermeyer of the sector trend.

The decision of one vice-chancellor to move on, as Anton Muscatelli did, can have knock-on effects. His position at the University of Glasgow was filled by Andy Schofield of Lancaster University, who was replaced in turn as vice-chancellor by Glasgow Caledonian University’s Steve Decent.

Kim Peters, professor of management at the University of Exeter, said the need for financial management skills, which might be hard for someone on the academic track to acquire, could be contributing to the poaching of other vice-chancellors.

“The tertiary sector is entering a period of contraction and consolidation. Given that organisations are especially likely to pursue change when faced with external challenges, the churn is likely to continue.”

Several leaders stepped down amid financial challenges – Frances Corner at Goldsmiths, University of London and Ian Gillespie at the University of Dundee. Both positions have been temporarily filled, with searches for permanent leaders ongoing.

Richard Bolden, professor of leadership and management at the University of the West of England, said fiscal challenges have caused “significant turbulence” in leadership – but other factors such as artificial intelligence might soon start to have an impact.

“At the moment, it may seem that financial management skills are particularly significant, however, an ability to navigate massive digital disruption and also social change is going to be a really significant skill set for the future.”

About 35 per cent of the filled vacancies were promotions from within the same university, and 38 per cent were replaced by a senior leader from another UK institution.

Churn at the top therefore causes disruption throughout a university. Bolden said universities have a great capacity for continuing to function relatively effectively despite gaps in senior leadership, but it does limit their ability to be strategic and forward-looking.

Peters said appointing a new leader is often an indicator of large-scale organisational upheaval, with frequent change linked to reduced productivity, higher stress, lower morale, and increased staff turnover.

Some universities were forced to replace their leaders unexpectedly. James Tooley unsuccessfully reapplied for his own job after he was suspended by the University of Buckingham over allegations relating to a past relationship. And George Holmes was suspended by the University of Greater Manchester with the institution being investigated over fraud allegations.

Analysis of accounts shows that departures can sometimes be costly. Jane Roscoe left by “mutual agreement” after just over a year at the University for the Creative Arts, and received over £120,000 in compensation for loss of office. Similarly, Nick Braisby received an ex gratia compensation payment of £76,000 after stepping down at Buckinghamshire New University – along with £144,000 in deferred salary. He then subsequently became interim vice-chancellor at the University of Bradford.

Aleks Subic of Aston University is leaving for Australia in April, taking over at Torrens University. He follows Max Lu, previously of the University of Surrey, who has taken over at the University of Wollongong.

But none of the new appointees of UK universities have come from overseas, which could suggest a preference among search committees for people familiar with the UK context and its challenges, according to Peters.

While some in the sector will be crying out for “real transformational leadership”, Watermeyer said the innate conservatism of the sector may be contributing to the desire for a “safe pair of hands” in charge.

But he warned that international applicants might also be put off by “a sector in dire straits”, where the top jobs are paid significantly less than US peers but receive plenty of scrutiny over their pay.

The most left-field appointment was perhaps Paul Kett at London South Bank University, who was previously a consultant and high-ranking civil servant.

Before his tenure, LSBU was briefly led by interim co-vice-chancellors, which Bolden said should be a model that some institutions consider in the long term.

“Increasingly the size of our organisations, the complexity, the challenges, may begin to raise questions as to whether this is a job that’s maybe too big or too complex for a single person.”

patrick.jack@timeshighereducation.com

Universities with new leaders

- Aston University: Search under way for Aleks Subic’s successor. He has taken up a post in Australia

- Bath Spa University: Georgina Andrews succeeded Sue Rigby, who became leader at Edinburgh Napier University

- Buckinghamshire New University: Damien Page succeeded Nick Braisby in February last year. Braisby then became interim vice-chancellor at Bradford

- Canterbury Christ Church University: Claire Ozanne will succeed Rama Thirunamachandran, who is retiring after 13 years in post, in April

- Edge Hill University: Michael Yong replaced acting vice-chancellor Lynda Brady

- Edinburgh Napier University: Sue Rigby was previously vice-chancellor at Bath Spa

- Glasgow Caledonian University: After Steve Decent left, Mairi Watson was appointed

- Goldsmiths, University of London: David Oswell serving in interim charge while replacement to Frances Corner is found

- Keele University: Kevin Shakesheff replaced the retiring Trevor McMillan

- Lancaster University: Steve Decent succeeded departing Andy Schofield

- Lincoln Bishop University: Andrew Gower took over from interim leader Karen Stanton

- Liverpool Hope University: Penny Haughan replaced Claire Ozanne, who left for Canterbury Christ Church

- London South Bank University: Paul Kett joined from PwC

- Norwich University of the Arts: Ben Stopher was promoted from deputy vice-chancellor

- Nottingham Trent University: Hull’s Dave Petley succeeded Edward Peck who now chairs the OfS

- Oxford Brookes University: Helen Laville succeeded Alistair Fitt, who retired

- St Mary’s University, Twickenham: Looking for a successor to the retiring Anthony McClaran

- Teesside University: Mark Simpson will replace retiring Paul Croney in September

- The Open University: LSBU’s leader Dave Phoenix took over from interim vice-chancellor

- The University of Buckingham: David Cole became interim vice-chancellor after James Tooley's term ended

- University for the Creative Arts: Jane Roscoe stepped down by “mutual agreement” after just over a year in charge

- University of Aberdeen: Internal appointment Pete Edwards replaced George Boyne

- University of Bedfordshire: LSBU’s interim co-vice-chancellor Deborah Johnston will take over after Rebecca Bunting retired

- University of Bradford: Gillian Murray will take over from interim Nick Braisby

- University of Brighton: Donna Whitehead succeeded the retiring Debra Humphris

- University of Dundee: Nigel Seaton serving as interim leader after Ian Gillespie quit over financial crisis

- University of Essex: Frances Bowen will take over from interim leader Maria Fasli

- University of Glasgow: Andy Schofield joined from Lancaster after Anton Muscatelli left

- University of Greater Manchester: George Holmes suspended over fraud allegations

- University of Hertfordshire: Quintin McKellar retired, replaced by Anthony Woodman

- University of Hull: Tom Lawson will take over from Dave Petley

- University of Nottingham: Jane Norman appointed to succeed departing Shearer West

- University of South Wales: Osama Khan will join in May after interim role filled by James Gravelle

- University of Southampton: Mark Smith leaving to become pro vice-chancellor at Oxford

- University of Stirling: Search for a successor to Gerry McCormac is under way, who is retiring after 16 years in charge

- University of Strathclyde: Stephen McArthur, formerly associate principal, took the top job

- University of Surrey: Stephen Jarvis appointed after Max Lu left for the University of Wollongong

- University of the Arts London: Karen Stanton, formerly interim vice-chancellor, took over permanently – she was also previously interim leader of Lincoln Bishop University

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?