Browse the full Times Higher Education World Reputation Rankings 2017 results

Leading universities in Asia are now considered more prestigious among top academics than many distinguished Western institutions, according to the Times Higher Education World Reputation Rankings 2017.

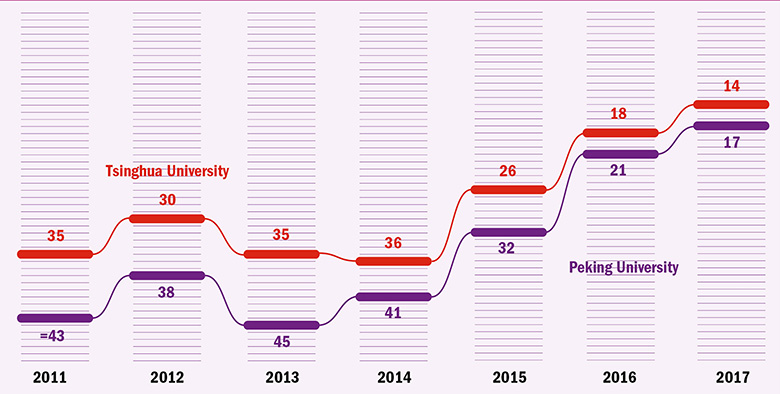

China is one of the standout performers: Tsinghua University enters the top 15 for the first time, jumping four places to 14th, while Peking University makes its debut in the top 20, climbing four places to 17th.

They overtake leading universities in the US and the UK including Imperial College London, the University of Pennsylvania and Cornell University.

Meanwhile, the University of Hong Kong features in the top 40 for the first time in five years after climbing six places to 39th, ahead of King’s College London, the University of British Columbia and LMU Munich.

Elsewhere in Asia, the University of Tokyo now has a stronger reputation than Columbia University, according to the table, while Seoul National University is considered more prestigious than the University of California, Davis.

Top universities in Belgium, France and the Netherlands have also lost ground as universities in Asia have become more prominent brands on the global stage.

The World Reputation Rankings are based on an invitation-only opinion survey of senior, published academics, who were asked to name no more than 15 universities that they believe are the best for research and teaching in their field, based on their own experience.

- How to get the best out of your PR objectives

- Brand: that’s you, in a word

- How the experts voted for the most prestigious universities

- Our people are our brand incarnate

- To stand out, master the three Rs

However, the results of the latest THE World University Rankings, which largely measures research performance, suggest that there is a gap between the perceived and actual performance of the continent’s top universities. Asia’s universities do not feature as highly in this list, despite recent improvements.

Simon Marginson, director of the Centre for Global Higher Education at the UCL Institute of Education, said that there is “no doubt that the reputation of China’s top two universities has run ahead of their actual achievements”.

“The achievements are remarkable but uneven. In terms of high citation research in mathematics and complex computing, Tsinghua is now number one in the world, ahead of MIT [Massachusetts Institute of Technology], and it is fourth in physical sciences and engineering. Yet Tsinghua is much less strong in research in medicine, [the] social sciences and humanities,” he said.

But Professor Marginson rejected the notion that China’s universities have been overhyped and predicted that the performance of the country’s top institutions will soon catch up with their growing prestige.

“Such is the rate of improvement that their reputation today is likely to be chased down by their real performance tomorrow,” he said.

Zhou Zhong, associate professor in comparative and international education at Tsinghua University, said that China’s determination to develop world-class universities through a number of excellence initiatives since the 1980s is a key factor in its success.

He added that Tsinghua’s rising reputation was partly due to several major “scientific and technological breakthroughs in recent years”, which have “drawn wide attention across the world to some of Tsinghua’s core strengths in big science”.

“Improved research infrastructure and, very strategically, the newly developed tenure system have all helped to both pull and push the academics to develop a publish or perish culture,” he said.

THE World Reputation Rankings 2017: top 10

| Reputation rank 2017 | Reputation rank 2016 | World rank 2016-17 | University | Country |

| 1 | 1 | 6 | Harvard University | United States |

| 2 | 2 | 5 | Massachusetts Institute of Technology | United States |

| 3 | 3 | 3 | Stanford University | United States |

| =4 | 4 | 4 | University of Cambridge | United Kingdom |

| =4 | 5 | 1 | University of Oxford | United Kingdom |

| 6 | 6 | =10 | University of California, Berkeley | United States |

| 7 | 7 | 7 | Princeton University | United States |

| 8 | 8 | 12 | Yale University | United States |

| 9 | 11 | =10 | University of Chicago | United States |

| 10 | 10 | 2 | California Institute of Technology | United States |

Keep it real: your name’s on the line

Even universities renowned for excellence have been challenged by a tide of public disdain for experts. This is how they are responding

When former University of Michigan president Harold Shapiro returned to the institution earlier this year to celebrate the university’s bicentennial, he said that the US now faces an environment characterised by high levels of “cultural, social, economic and political anxiety”.

“It is disheartening to witness the growing prominence of the notion that institutions of all kinds are not to be trusted – that there is little to separate truth from fiction,” he said.

Universities, some would argue, are facing an identity crisis in which the core values for which they stand – truth, evidence, freedom of speech – are being challenged.

But Emma Leech, director of marketing and advancement at the UK’s Loughborough University, says that this climate can be seen as an opportunity for higher education institutions.

Loughborough now increasingly interacts with bloggers and other opinion influencers, as well as students and alumni, to encourage new groups of people to tell stories about the university, she explains.

View this year's World Reputation Rankings methodology in full

“In terms of communications strategies, [the] post-truth [era] has made us really think about how we share and disseminate news, and we don’t just use traditional channels any more,” Leech says, adding that many members of the public now see people who are similar to themselves as a credible source of information, equal to a technical or academic expert.

But she notes that while Loughborough has taken steps to adjust its communication strategy to address the worrying trend towards the mistrust of experts, it has found it difficult to assuage academics’ “fear of being dumbed down”.

There is also still a “snobbery” in the academy and a disdain attached to scholars who communicate their research findings to the media, Leech says.

“I’ve worked in higher education for 28 years, and [this problem] has not gone away,” she says.

“The world that we live in now means that everybody has instant access to knowledge, information and the latest thinking at the touch of a button. There isn’t time to write a standard press release five times as we would have done in times of old to stop academics feeling uncomfortable that somehow their research was going to be dumbed down if disseminated publicly.”

The question of how institutions can navigate a “post-truth” world has relevance for the majority of universities in the Times Higher Education World Reputation Rankings 2017.

More than two-fifths of the 101 universities in the table (42) are based in the US, while one in 10 is situated in the UK. The spread of “fake news”, the rise of “alternative facts” and the dismissal of experts were features of the campaigns that led to both the UK’s vote to leave the European Union and Donald Trump’s election as US president in 2016.

This ranking is characterised by its stability, owing in part to the nature of reputation as a lagging indicator. But there are some noticeable changes since last year.

China has improved its standing, with six institutions in the top 100 (the same number as Germany and Japan), up from five last year. Tsinghua University enters the top 15 for the first time in 14th place (up from 18th), while Peking University makes its debut in the top 20 at 17th position (up from 21st). All the other Chinese institutions in the ranking have also either maintained or improved their positions.

Meanwhile, the University of Copenhagen is back in the list in the 81-90 band after having fallen out last year following budget cuts that led to the laying-off of more than 500 staff – or 7 per cent of its workforce – and the removal of some of its degree programmes.

And the University of Chicago climbs into the top 10 for the first time, claiming ninth place, on the back of an increase in the esteem of its research and teaching. The university has steadily improved its position since the rankings began in 2011, when it featured at 15th place.

The Free University of Berlin is another riser, jumping from the 71-80 band into the 61-70 band this year.

Peter-André Alt, the university’s president, says that the institution lost half its budget, half its aca demic staff and half its students after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

But a reorganisation of the institution that began in the mid-1990s has resulted in a steady improvement of the university’s research prowess, he adds.

Search our database for the latest global university jobs

The changes featured the introduction of new incentives for the promotion of academics; targets for individual scholars and departments; and a performance-based allocation of funding for research.

“We are now the most successful German university when it comes to [securing] funds from public foundations,” Alt adds.

Funding is certainly critical to institutional success, but many of today’s challenges around reputation have little to do with cash.

James Hilton, dean of libraries and vice-provost for academic innovation at the University of Michigan, ranked 15th, says that universities historically have tended to “withdraw” from conversations around the differences between facts and opinion “because we don’t want to look political”.

Higher education institutions have also been “reticent”, reluctant to make a public case for their value in society, he says, citing the debate around the “escalating cost” of degree study as an example of a topic where universities “lost the framing of the conversation”.

But Hilton says that the current climate is leading more institutions to be “less ivory tower on the hill and more engaged in public discourse”.

“Research universities are communities bound together with a shared commitment to analysis and the creation of things the world has never known before. We live in the world of facts and analysis. So that’s a part we’re going to absolutely have to engage in,” he says.

One way in which Michigan is achieving this is by running a series of free online “teach-outs” that allow the public to interact with students and academics on campus to learn about and discuss pressing national and international issues. Topics discussed so far have included the future of the Affordable Care Act (better known as Obamacare); how to communicate science; and fake news, facts and alternative facts.

Browse Times Higher Education’s full portfolio of university rankings

Earlier this year, the university created a course aimed at teaching students how to identify fake news.

Similar moves have been made elsewhere. Last year, the University of Cambridge, which shares fourth position in the Reputation Rankings, established the Winton Centre for Risk and Evidence Communication to ensure that facts on important issues are presented in ways that are accurate, transparent and relevant.

Alan Pinon, communication and marketing director at the University of Michigan Library, argues that the “fundamental” strategy for how universities manage their reputations has not changed. It still boils down to “good content, appealing to emotions, using the right channels at the right time, and sticking to solid ethics”, he says.

However, he notes that while social media channels have become more important, many universities “make missteps” by giving responsibility for digital activity to students or staff with no communications background.

“If a fake news story starts to pick up steam, a professional communication staff will catch wind of it early and be able to get in front of it. If they happen to miss it or it propagates too fast, the established communication network and skills of a good team that has a plan in place for issue management will be vital to mitigating the damage it can do,” Pinon says.

For Jeremy Lucas, head of corporate at Ogilvy PR, the key way that universities can regain trust is to ditch the traditional silos of business-to-business and business-to-consumer campaigns and to invest in “business-to-human communications”.

“Business-to-human is a way of putting emotions and humanity at the heart of your corporate brand in a way that unites all audiences,” he says.

For universities, “it’s very much about how do you take a cold, grey research endeavour and make it appropriate and applicable and interesting at a human level…That is now how their reputation is being moulded and shaped.”

Pedal to the metal: China’s continued rise in the reputation rankings

A striking feature of the Times Higher Education World Reputation Rankings is the continued rise of China. Tsinghua University has climbed 21 places in the table since the ranking began in 2011 to reach 14th place this year, while Peking University has jumped 26 spots during this period to 17th. They overtake distinguished institutions across the globe including Imperial College London, the University of Pennsylvania and Cornell University.

The results suggest that 22 years’ worth of “Excellence Initiatives” – large injections of additional government funding aimed at accelerating universities’ performance – has paid off. China’s latest project, dubbed World Class 2.0, was announced in 2015. It aims to establish six of its universities in the leading group of global institutions by 2020, and for some of those to reach top 15 status by 2030.

It seems to be on track to achieving this goal. Peking University has already entered the global top 30, claiming 29th place in the latest THE World University Rankings. China also came second in last year’s Nature Index, which tracks the number of articles published in leading natural science journals by nationality of researcher. However, it is worth noting that while the country has a handful of well-known higher education institutions, the bulk of its research universities have yet to become household names on the world stage.

Nevertheless, if the country continues to pump billions of yuan into its institutions and focuses on boosting the quantity and quality of its research output, then there is no doubt that its leading universities’ overall performances will catch up with their growing prestige.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?