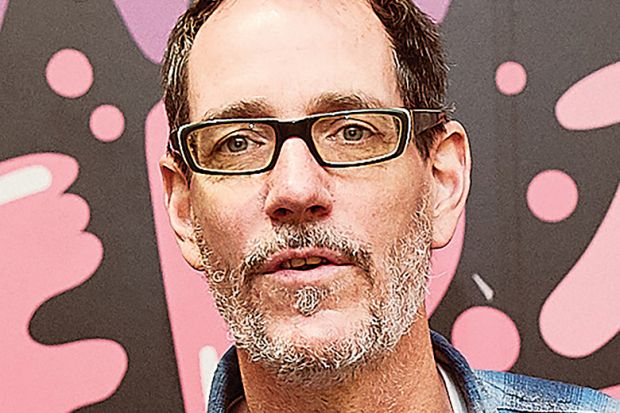

Caspar Melville, lecturer in global creative and cultural industries at SOAS University of London, is a former music journalist, radio presenter, club promoter and editor of New Humanist. His book, It’s a London Thing: How Rare Groove, Acid House and Jungle Remapped the City, was published by Manchester University Press in November.

When and where were you born?

In my parents’ flat in Highbury, near the old Arsenal ground in north London, in 1966.

How has this shaped you?

I’m a Londoner through and through. London has shaped every aspect of my life; although I have lived in the US, I never feel at home anywhere else. It’s a frustrating, sometimes ugly, mess, but this means that everyone in the city – rich and poor, every ethnicity, hipster and geezer – has a shared experience of crowds, noise, dirt and roadworks, which bonds us together. London also has one of the world’s best music cultures, which makes it all worthwhile.

How did you end up as an academic?

I started out as a music journalist for small, independent black music magazines like Blues & Soul and Touch. In 1992, I moved to the US when the country failed to kick the Tories out (sigh). I lived in San Francisco, where I started a jazz magazine with some friends, called On the One. There was not a lot of money in it, but we put out a really good magazine for a few years until it became economically unsustainable. In 1997, I moved back to London and made the decision to find another way to write about music. I had come across the work of Paul Gilroy, particularly The Black Atlantic, and found it inspiring because he writes about black popular music in a serious way. I went to Goldsmiths, University of London to do an MA in media and communications because that was where Gilroy was teaching at the time. My main purpose for going to university was to write a book on London club culture, the music that had formed me and that I felt was seriously underestimated or ignored in the academy. I managed to convince the British Academy to fund my PhD, which was supervised by Angela McRobbie at Goldsmiths. By 2012 [after spells as executive editor at the political website openDemocracy and then at New Humanist], I was getting restless: I enjoyed being a magazine editor, but I was itching to get back to music. I saw a job at SOAS to run a new MA in global creative and cultural industries. It took me a few years to figure out what “creative and cultural industries” were and how to teach a group of postgraduate students from all across the world, but after a few years I settled in and revisited the idea of the book.

It’s a London Thing is about black musical cultures of the 1980s and 1990s. Why haven’t these cultures been much studied by academics, and why should they be?

In black music studies, jazz and hip hop have received the lion’s share of the attention. Dance music has been largely ignored as it is assumed to be trivial and apolitical. The club scenes of London that fascinate me – from reggae sound systems to rare groove, house and jungle – have been crucial sites where black Londoners have built their own semi-autonomous moral economies, providing employment and training, security and access to a “counterculture to modernity” against the backdrop of brutal forms of racism and urban deindustrialisation. Every now and then, the cheerleaders of UK plc take notice, folding club culture into their narrative of London as the vibrant heart of the UK’s creative economy, but they rarely engage with the real moral, economic or social impact of this form of every-night culture.

Do you ever encounter snobbishness from academics about the areas you study?

No one has ever said to me that this area is not worthy of study. Instead, academics often say that my work sounds “cool”, but because I’m talking about things they have never heard of or thought about, they don’t really engage with it as a contribution to knowledge or an academic area that deserves the kind of critical engagement that, say, politics or philosophy commands. I want to have arguments, but in order to do that it’s necessary to lay the history out, which is what my book tries to do. Most people outside academia I’ve spoken to seem thrilled that these things are finally getting the academic attention they merit.

What are the most valuable things about SOAS?

SOAS is a unique institution, with a very distinct history as an imperial training college and then a centre for decolonial thought. It is in a continual struggle with its own history, which makes it an exciting, if sometimes frustrating, place to be. Its real strength lies in its diversity. On my MA, the vast majority of students are not from the UK; last year, I had 22 students from 20 countries. For those of us trained in the UK system alongside people from the same country, this can be a real challenge; you can’t fall back on a shared set of cultural assumptions or references.

What keeps you awake at night?

I usually sleep soundly, but while I was finishing the book I was beset by anxiety and frequently woke in the middle of the night panicking that the book was terrible and I would be humiliated. I think this is an inevitable part of the creative process, which shows that you are taking it seriously. Writing takes you to the very limits of yourself; you can’t improvise or blag it – as I tend to do in other arenas of my life – so you just have to live with it. It feels great when it’s over.

john.morgan@timeshighereducation.com

Appointments

Amanda Coffey has been appointed deputy vice-chancellor at the University of the West of England. She will move to Bristol in April, leaving her post as pro vice-chancellor for student experience and academic standards at Cardiff University, where she has worked since 1990. The sociologist, who led efforts to tackle the ethnic minority attainment gap at Cardiff, said one of her priorities would be “to ensure that all students realise their potential while they are studying at UWE and are enabled to succeed”.

Mark Hoffman is joining Australia’s University of Newcastle as deputy vice-chancellor (academic). Professor Hoffman, who has been dean of engineering at UNSW Sydney for the past five years, will join Newcastle in March. “Professor Hoffman’s commitment to serving the community through cross-disciplinary education and research, along with his achievements in work-integrated learning programmes, will be an enormous asset as we move forward with our strategic plan for the next five years,” said Alex Zelinsky, Newcastle’s vice-chancellor.

Jacqueline Lo has been appointed pro vice-chancellor (international) at the University of Adelaide. She is currently associate dean, international, in the College of Arts and Social Sciences at the Australian National University.

Stephen Riley has been named the new head of Cardiff University’s School of Medicine. He is currently the school’s dean of medical education.

The Chinese University of Hong Kong has named Raymond Chan Kwok-hong as the university dean of students. Professor Chan is currently an associate professor in the department of social and behavioural sciences at City University of Hong Kong. The Chinese University of Hong Kong has also named Lin Zhou, currently university chair professor at Shanghai Jiao Tong University, as dean of its Faculty of Business Administration.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?