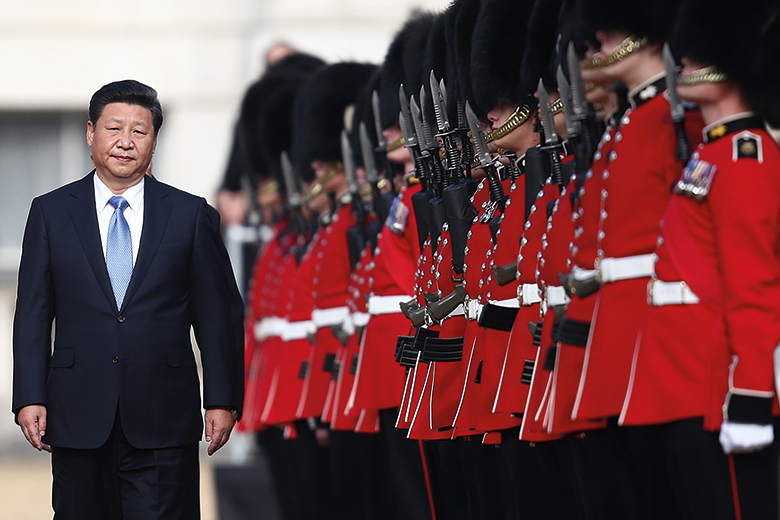

The extraordinary rise of Xi Jinping was, understandably, the main talking point of the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC) in October. Thanks to the president’s relentless consolidation of his personal power base within the party and the official encouragement of something approaching a cult of personality, comparisons with Mao were inevitably made by Western media outlets.

The symbolic culmination of Xi’s ever-tightening grip on power was the unprecedented incorporation of his personal political theory, known as his “Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era”, into the party’s constitution. Xi’s 14-point plan to turn China into a “great modern socialist country” that is “prosperous, strong, democratic, culturally advanced, harmonious and beautiful” has been accompanied by equally strong ambitions on the international stage. At the 2017 World Economic Forum annual meeting in Davos, he cast himself as the leading champion of free trade and the fight against climate change, sensing the vacancy created by Donald Trump’s America First foreign policy and a European Union increasingly looking inward as it grapples with Brexit. Trump’s extravagant courting of Xi during his recent Asian tour and his refusal even to broach the issue of human rights only underscored China’s rising global standing.

Amid all of this, it was easy to overlook some comments made during a press conference at the 19th Congress by Chen Baosheng, the minister and party secretary of the Department of Education. When asked to outline the blueprint for the future of Chinese education, Chen predicted that, by 2049, the centenary of the People’s Republic of China, the country will have become the centre and leader of the world’s educational development. He also foresaw that, by the same date, China will have become the most popular destination for international students. As reported by Chinese radio, these comments clearly reflect the global ambitions of Xi’s “China Dream” of national rejuvenation.

Although obviously part of the propaganda offensive to be expected during the congress, the minister’s comments find some justification in the remarkable pace of internationalisation in China’s educational sector during the past three decades. Chen was able to cite numerous indicators of this. For instance, China has established educational collaboration projects with more than 180 countries and regions and completed mutual validation of academic degrees and diplomas with 47. At the same time, it has founded 516 Confucius Institutes in more than 140 countries and provided Mandarin Chinese teaching in 1,000 secondary and primary schools overseas. As Chen observed, China has become home to the world’s third-largest community of international students and is the number-one destination for international students in Asia.

Of course, these trends must be set against the growing number of Chinese students who have left China to study abroad, who now constitute the biggest international student cohort by some distance in US and UK universities (where 330,000 and 91,000 Chinese students are based, respectively). According to figures from China Daily, there were 544,500 Chinese studying abroad (including primary, secondary and higher education) in 2016, more than three times the 179,800 recorded in 2008. And the billionaire Chinese education entrepreneur Yu Minhong, whose wealth primarily stems from training Chinese students in English, predicts that China will send even more of its young people to study abroad in the future, with between 400,000 and 500,000 attending colleges and universities alone. The perceived premium of a US or UK degree among the Chinese population does not look like diminishing in the immediate future.

There is, however, a further context for the minister’s ambition to dominate global higher education. This is the steady increase in political regulation of academic life during Xi’s presidency. The sacking of two academics prior to the 19th Congress received little attention. But the silencing of Tan Song, a committed researcher on the sensitive subject of land reform during the 1950s at Chongqing Normal University, and Shi Jiepeng, assistant professor in ancient Chinese language at Beijing Normal University, who was reportedly ousted for unpatriotic comments on the Chinese social media site Weibo, are just the most recent in a series of such measures designed to discourage any criticism of the regime from the academy. In a special commentary on this issue prior to the 19th Congress for Deutsche Welle, Germany’s international broadcaster, former academic Wu Qiang explained how scholars are being ordered to submit their social media accounts for monitoring and their passports for screening before overseas academic visits.

This assault on academic freedom under Xi may bring more echoes of the Mao era but it has not been sufficient to galvanise a strong response in the West. While the long-standing suppression of human rights and freedom of expression in China is deplored, it is not allowed to interfere with diplomatic or, crucially, trade relations.

In August, however, the issue of academic freedom was brought inescapably back to home ground when it emerged that Cambridge University Press (CUP) had bowed to Chinese pressure and censored more than 300 online-access articles in its prestigious journal The China Quarterly.

Although the publisher reversed the move within days, after widespread criticism and threats of boycott, the story has not ended there. In November, the Financial Times revealed that Springer Nature, one of the world’s largest academic publishers, had, at the behest of Beijing, blocked access on its Chinese website to more than 1,000 academic articles containing key terms such as “Tibet”, “Taiwan” or “Hong Kong”, which China deems politically sensitive. The publishing giant defended its action, denying charges of censorship and claiming that it was merely complying with China’s “regulatory requirements”.

Other signs of publishers bowing to pressure from Beijing that have since emerged bring the issue of censorship even more firmly into the Western academic sphere. Allen & Unwin, it emerged in mid-November, has suspended publication of a book intended for the Western market, Silent invasion: How China is turning Australia into a puppet state, by Clive Hamilton, a professor at Charles Sturt University in Canberra. The publisher claims that the decision was the result of “extensive legal advice” over the possibility of defamation action. Hamilton, however, argues that Australians should not be bullied into silence by an autocratic foreign power (see Hamilton, page 36).

Some academic publishers, admittedly, are taking a firmer stance against any Chinese interference, but the fear must be that, without a concerted response, a core principle of academic integrity might simply fall by the wayside. As Kevin Carrico, lecturer in Chinese studies at Macquarie University, put it in a recent essay , “these types of attacks on academic freedom for access to the China market could gradually become the new normal for all of us: shocking the first time, but gradually something to which we will all grow accustomed”.

China’s strategy, moreover, may be extending beyond academic publishing. The censorship methods employed by the party are “much more pervasive and subtle than the widely recognised explicit demands”, observes Christopher Balding, associate professor of business and economics at the Peking University HSBC Business School in Shenzhen. In a recent piece on Chinese “soft power” for the China Policy Institute’s online journal, he argues that Chinese government-funded research centres at prestigious universities in the US and Europe will be unlikely “to accept research critical of government policy”, and he notes that Confucius Institutes have already used their “influence to censor discussion abroad of sensitive topics like Tiananmen Square, Tibet, Taiwan and human rights”.

The hesitancy across many of the key institutions of Western higher education – from publishers and universities to governments themselves – about confronting the new assertiveness of China perhaps signals a failure to comprehend the full extent of the challenge that it poses. The “New Era” of global expansion that President Xi and Minister Chen envision is one in which the subservience of freedom of expression to the demands of the state is a fundamental ideological tenet. If this ideology is no longer to be contained within the borders of China, the game is dramatically changing. As Jonathan Sullivan, director of the China Policy Institute at the University of Nottingham, recently tweeted: “I’m afraid we [in the West] are totally unprepared for the export of Chinese government ways and means”.

What, then, could prepare us? First, a wider and deeper understanding of both the Chinese government’s global ambitions and the strategies to achieve them is urgently needed. This must acknowledge that China now sees itself – and represents itself to its population – as a key global player with its own legitimate agenda for shaping global affairs. This agenda does not accept the terms and conditions of liberal democracy.

Second, Western institutions – and particularly academia – need to reflect on how the assertion of the academy’s core values can appear so half-hearted when put to the test. This is not just a question of economic interests and the pragmatic acquiescence that they beget. It is perhaps a problem with the trajectory of Western liberal democracy itself: that having held sway over the globalisation process for so long it has become complacent. Unaccustomed to serious challenge, its ideological armour has become rusty. But now the challenge is coming, and we need to confront the consequences of not rising to it.

Tao Zhang is a senior lecturer at Nottingham Trent University’s School of Arts and Humanities.

Springer Nature responds: ‘we are required to take account of local rules’

In a statement to Times Higher Education, Springer Nature says: “As a global publisher, we are required to take account of the local rules and regulations in the countries in which we distribute our published content. China’s regulatory requirements oblige us to operate our SpringerLink platform in compliance with their local distribution laws. These local regulations, which are enforced by our distributors, who are the officially appointed guardians of all content, only apply to local access to content.

“This does mean that access to a small percentage of our content (less than 1 per cent) is limited in mainland China but remains accessible in the 180-plus other markets in which our content is distributed, and in China itself via other means. This action is deeply regrettable but has been taken to prevent a much greater impact on our customers and authors and is in compliance with our published policy. This is not editorial censorship and does not affect the content we publish or make accessible elsewhere in the world. It is a local content access decision in China done to comply with specific local regulations.

“In not taking action, we run the very real risk of customers not being able to access any of our content. We do not believe that it is in the interests of our authors, customers or the wider scientific and academic community, or to the advancement of research, for us to be banned from distributing our content in China. Access to 99 per cent of Springer Nature content is therefore safeguarded for all our customers in China and we will continue to work with the regulator and other Chinese authorities to minimise the content affected, [and to] reduce and ideally eliminate these restrictions on behalf of the global research community and wider society. We remain absolutely committed to safeguarding the integrity of the scientific record by publishing robust and insightful research across the world, supporting the development of new areas of knowledge.”

Cambridge University Press and Allen & Unwin did not respond to invitations to comment.

Scholarly intimidation is being imported into Australia under official Communist Party licence in the guise of patriotism

It’s a truism that we take our freedoms for granted until they are taken away, but recent events have really driven that home to me. In November, my imminent book exposing the subversive activities of the CPC in Australia was dropped by its publisher because it feared retaliation from Beijing.

I never imagined that such a thing could happen. Allen & Unwin has been my publisher for many years and its enthusiastic backing for my new book gave me the sense that we were taking on the powerful Chinese state together. Then, suddenly, it abandoned the battlefield, leaving me out there on my own, looking over my shoulder.

The reason that I was given had the merit of honesty – “threats to the book and the company from possible action by Beijing” and, especially, the possibility of vexatious legal actions against me and the publisher by Beijing’s “agents of influence” in Australia. Beijing-linked Chinese billionaires have in recent times launched defamation actions against major news outlets in Australia, with cases winding their way through the courts.

Cyber-attacks against the company were also mentioned. And the likelihood of being denied access to cheap printing works in China. No threats were actually made; the shadow now cast by Beijing over Australia was enough. The publisher did a last-minute assessment of the risks of publishing, decided that it was not worth it and asked me to come back with my manuscript in a year or so when it would reassess.

The book describes an orchestrated campaign by CPC agencies to influence Australia and silence China’s critics. One element of the campaign is the massaging of senior Australian journalists with all-expenses-paid junkets to China in the hope (fully realised) that they write articles more sympathetic to the country and its leader. It details an extensive network of research collaborations and personal links between Australian scientists and researchers at Chinese military universities, part of China’s programme of sucking advanced knowledge from the West to boost its industrial and military capabilities.

One of the big questions that I felt I had to answer is how it came to pass that the most influential members of Australia’s policy and intellectual elite were won over to Beijing’s view of the world to such an extent that they now advocate for China’s interests over Australia’s. Who are these agents of influence and how do they manage to dominate the debate?

Using defamation laws to suppress criticism of China in a Western country seems to be an entirely new tactic. Yet hints can be found in manuals for Communist Party operatives. An internal document that details the ways in which the party is subduing Taiwan calls on cadres to “utilise legal warfare and public opinion warfare”. In mid-December, a People’s Daily editorial in effect endorsed use of “the weapons of law” to punish those in the West making “incorrect reports about Chinese”.

I don’t know whether my publisher carried out an assessment of the risks of not publishing the book. Judging by the flood of support that I have received, and the worldwide media interest in the story, the downside of reputational damage and sagging staff morale may be bigger than the publisher had guessed. I worry about the message that has been sent to other publishers. Will they find excuses to reject proposals for books that might offend Beijing? Will other scholars decide to stay on safe ground for fear that their manuscripts may end up gathering dust on their bookshelves?

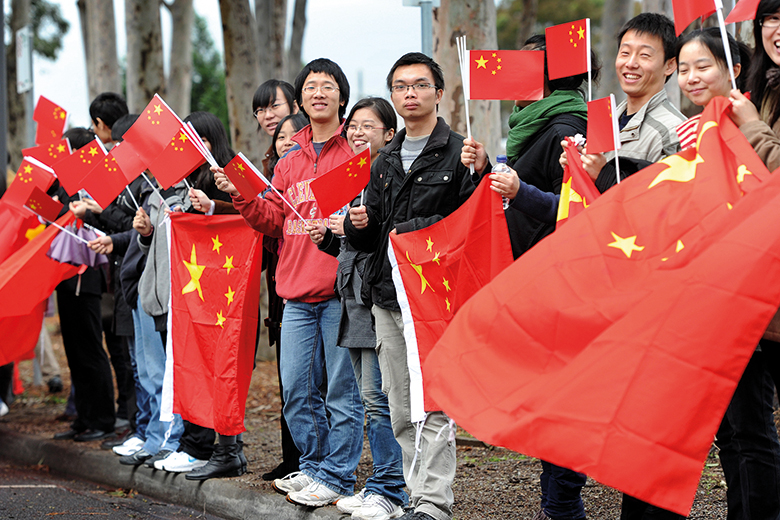

Already, academics in Australia work under a subtle silencing regime. Emboldened by China’s economic might and President Xi’s muscular nationalism, Chinese students at Australian universities are on the alert for any offence by their teachers. A lecturer who used a map that, if you looked carefully enough, showed Indian rather than Chinese lines in a disputed Himalayan border region was denounced on social media. The lecturer was forced to apologise.

Memo to all staff: In your classes, please acknowledge the validity of any and all Chinese territorial claims.

Reflecting on this new culture of denunciation, Australia’s leading sinologist, Swinburne University’s John Fitzgerald, had argued that “scholarly intimidation” is being imported into Australia under official Communist Party licence in the guise of Chinese patriotism. These trends are eroding the foundational principles of the university, those of free and open inquiry and the contest of ideas. Yet Xi has publicly declared that the CPC is waging a war against Western values, including academic freedom. Until now, we thought that the war was being fought against the spread of Western values in China. Now, the primacy of Western values in the West is being challenged.

Although they deny it, the money that pours into Australian universities from China has an insidious silencing effect. It’s not just the income from student fees (as much as 15-20 per cent of total revenue at some of the leading universities) but cash for Confucius Institutes, multimillion-dollar gifts from Chinese benefactors and scores of lucrative joint research agreements with Chinese universities.

And so, under pressure from Chinese diplomats, the University of Sydney banished the Dalai Lama to an off-campus venue and banned use of the university’s logo at his lecture in 2013. At the prestigious Australian National University, the head of the Chinese students’ association allegedly walked into a busy campus pharmacy in 2016 and angrily pointed to the Epoch Times, the Falun Gong newspaper. He began shouting at the pharmacist, demanding “Who authorised you to distribute this?” Intimidated, the pharmacist removed the offending newspapers. University authorities did nothing.

Among those most dismayed at the dumping of my book are those Chinese-Australians who settled in this country to escape the strictures of the Communist Party yet feel increasingly alarmed as they see its growing influence here. Over the past 15 to 20 years they have been outnumbered and outspent by pro-Beijing immigrants arriving in Australia, including billionaires with links to the CPC.

In the course of researching my book I spoke to many of those Chinese-Australians. As I formed a picture of their lives, I became offended at the fact that large numbers of Australian citizens live in fear of being pressured and penalised by an autocratic foreign government if they express their political opinions. Anonymous phone callers issue dark warnings to those who step out of line. I heard of a visa being refused to a man wanting to visit his dying mother, and of a brother’s business in China being closed down to punish his relative in Australia.

But never for a moment did I think that the reach of the Chinese government would be used to penalise me. Yet as one of my Chinese-Australian friends reminded me: “We are in the same boat.”

In a coda to this story, my manuscript has now been rejected by an initially enthusiastic university press, ostensibly for the same reason as Allen & Unwin. However, the grapevine tells me that the university became anxious about the river of gold from its Chinese students drying up if it were to publish a book critical of the CPC. To have one’s central thesis vindicated in this way is cold comfort.

Clive Hamilton is professor of public ethics at Charles Sturt University in Canberra. He is seeking a publisher for his book.

Partnerships need to be carefully constructed by all those involved to guard against disguised motivations with the capacity to trump the seeking of truth

The emergence in the West of the “neoliberal university”, with its market forces and its corporate power structures, has hardly encouraged the research, publication, teaching and debating of what Chomsky calls “unwanted truths”. But nor is it true that undaunted truth-seeking was previously the consistent default position of Western academic institutions. The eminent University of Chicago political scientist Hans Morgenthau complained in the mid-20th century of the scholarly habit of “conformist subservience to those in power”. The reality is that academic freedom must be fought for, won and defended – and sometimes lost. As well as founding the realism school in international relations, Morgenthau also envisioned the phenomenon that for many is emerging as another major threat to academic freedom: China’s rise.

Despite legal reforms to the governance of higher education, the absence of effective university autonomy – the institutional counterpart of academic freedom – has a direct but not uniform impact on the teaching and research undertaken by Chinese scholars, especially in the social sciences and humanities. The overriding concern of the CPC with social stability, and its concomitant preoccupation with the historical and actual existing legitimacy of its own rule, undermines academic freedom in universities. Measures include surveillance and restrictions on the content of courses and the research deployed to support it. Some scholars have referred to the “deactivation” of the student population. Autonomous student demonstrations were a common feature of university life in the early years of the post-1978 reform era. They have all but disappeared since the repression of the student-led Democracy Movement in 1989.

In spite of these restrictions, Chinese universities feature in the top 100 of university rankings and have nurtured partnerships with leading universities all over the world. These are welcome developments. But such partnerships need to be carefully constructed by all those involved – including student and academic unions – to guard against mission creep or disguised motivations with the capacity to trump the seeking of truth. Research by the University of Lincoln’s Terence Karran has shown that levels of academic freedom vary across Europe too, in the face of different political, economic and legal contexts. Academic freedom is a multilayered rather than absolute ideal, which requires multiple inputs to remove myriad obstacles.

State-organised censorship is part of the context in China. Chinese scholars have become skilled at writing up fieldwork in language that does not alert the censors – or, if it does, leaves room for mediation. Of course, this does not always work out well, but it is preferable to the alternatives, which range from detention and dismissal to self-censorship and moral or actual resignation. Despite the well-documented increase in censorial measures, high-quality research remains eminently possible in China. As I have argued elsewhere, it is often generated via institutional academic cooperation at all levels – from university partnerships to networks of scholars. Imagine what could be achieved if the CPC relaxed censorship and permitted a more open approach to research that revealed “unwanted truths” without fear of the consequences.

Evidence to date, however, suggests that the opposite is happening. In the case of the Soas-owned journal The China Quarterly, where I serve as editor, our publisher, CUP, unilaterally blocked content deemed too sensitive for domestic consumption following an “instruction” from import agents through whom CUP publications are distributed in China. The usual themes were involved: Tibet and Xinjiang, Taiwan, the Cultural Revolution and the famine years following the Great Leap Forward. A more recent addition to the censor’s list is critical research on the absence of progress towards universal suffrage in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. The future of Deng Xiaoping’s formulation of “one country, two systems” has come under the scholarly spotlight since 2014’s large-scale protests in Hong Kong and the subsequent emergence of various strands of “localism” that deny – more or less – Beijing’s authority. To its credit, CUP responded rapidly to pressure from the global academic community in general and those associated with The China Quarterly in particular. It reversed its decision and made the 300-plus articles available again. One step forward.

In contrast, Springer Nature has complied with similar instructions to block more than 1,000 articles published in its scholarly journals but deemed unacceptable by the authorities in China. Many of these are peer-reviewed papers grounded in theory and carefully conceived methodologies. Like The China Quarterly articles that – at the time of writing – remain accessible in China, they contribute to our understanding of China and China’s place in the world. Access to this scholarship is now restricted to academics outside China, and Springer Nature’s decision undermines the potential for a common response to censorship wherever it may occur. Two steps back.

Springer Nature’s defence of its position is grounded in notions of safeguarding access in general, and I won’t rehearse it here. It seems to fly in the face of the views of the president of the International Publishers Association, Elsevier’s Michiel Kolman, who told a session on Chinese publishing at last year’s London Book Fair that publishing is a “motor of human progress first and a noble commercial endeavour second…an intellectual amber – capturing information and displaying it in its original form to the eternal benefit of humanity” (emphasis added).

In his famous Theses on Feuerbach, Marx argued that philosophers have interpreted the world, but the point is to change it. Either way, the universal – rather than absolute – ideal of academic freedom is worth upholding and defending as a vehicle for both ends. The point is, how?

First, we acknowledge that the threats to academic freedom are complex and change across time and space. Casual generalisations will not help to overcome them. Second, higher education institutions need to develop guidelines for partnership that at the very least do not undermine existing academic freedom and preferably uphold it. Third, journal editors need to be on the same page with regard to censorship of their published output: in short, reject it, and go on record as doing so – as many have done. Fourth, the detention and imprisoning of scholars is well documented by organisations such as Scholars at Risk and the Council for At-Risk Academics. Whether we are scholars, editors or indeed publishers, the people whom these organisations protect need our support and solidarity.

Obviously, these measures are not a magic bullet and are far from comprehensive. They are culled from my experience as editor of The China Quarterly, as well as from participation in public fora and conversations with colleagues since the “China Quarterly Incident” last August. I hope that these reflections contribute to the continuing debates and struggles against censorship and for academic freedom.

Tim Pringle is senior lecturer in labour, social movements and development at Soas, University of London, and editor of The China Quarterly.

An international academic publisher should not be helping the Chinese government to impose its view of the world

I regularly work in the Far East, visiting mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Macao. When working there I frequently conduct research projects, and publish with people in all of these places.

As the editor-in-chief of a major publication in my field, the Journal of Advanced Nursing, I also provide advice and training on how to write for publication. Censorship has never been a problem – until now. When I recently submitted a manuscript co-authored with Taiwanese colleagues to a journal published by Elsevier and edited in China, the editorial office instructed me to desist from using the term “Taiwanese” in the body of the text and to use “China” instead of “Taiwan” in providing contact details for the authors. This was done in the name of “relevant government regulations”. The manuscript was withdrawn because my Taiwanese co-authors refused to comply: they submitted elsewhere.

There has always been tension between mainland China and Taiwan and it is evident in both places. On a visit to Taiwan, in the process of explaining the publishing figures for my journal, I used the expression “greater China” to describe mainland China, Taiwan and Hong Kong collectively. This was in Kaohsiung, deep in the heart of Taiwanese Green Party territory, and the former minister of health was in the audience. She was soon on her feet berating me for using the term “greater”, asserting that Taiwan was not part of China. Compare that with a very recent visit to mainland China, where I was similarly berated from the floor for describing “greater China” as including Taiwan. I should have said “Chinese Taiwan” to indicate that it was not an independent country.

Frankly, the above exchanges are merely banter, because the protagonists are invariably friendly and an embarrassment to their colleagues; they simply have a point to make. This new twist to the story, being actively promoted by Elsevier, is more serious. There may be a case regarding the contact details of the Taiwanese co-authors; some Taiwanese would be perfectly happy with adding “China” to their address. However, to be told to stop describing an identifiable group of people as “Taiwanese” is inaccurate. Even the Chinese refer to the island land mass as “Taiwan”. The study involved a questionnaire translated into Chinese specifically for use with Taiwanese respondents. In Taiwan the classical Chinese characters are used, as opposed to the simplified form used in mainland China. It was not enough to use the Hong Kong “special administrative region” version written in classical Chinese characters because these are used slightly differently in both places. The questionnaire is labelled the “Taiwanese version” and is already known as such.

The censors were not only trying to force us to use their preferred style – this was an attack on academic freedom. It would have required, at the least, being inaccurate and, at worst, rewriting a piece of history, however small.

I have no issue with the Chinese government trying to impose its view of the world. We can all decide which view we wish to accept. I do, utterly, object to an international academic publisher complying and helping it to reinforce it.

A spokesman for Elsevier says that the journal in question is “a Chinese-owned publication and they and the editor make all the editorial decisions”.

Roger Watson is professor of nursing at the University of Hull.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Censors and sensitivities

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?