View data: UK vice-chancellors' remuneration, 2014-15

View data: UK university salaries for academic and non-academic staff, 2014-15

Anger over pay rises awarded to the so-called academic “fat cats” leading UK universities has bubbled up once again in recent months.

The bumper salary hikes enjoyed by some vice-chancellors were inevitably invoked by the University and College Union as it called a two-day strike over an “insulting” 1.1 per cent pay offer to rank-and-file staff for 2016‑17. Meanwhile, last November, the Daily Mail dedicated its front page to an exposé of what it termed the “shameless greed” and “exorbitant pay packages” of higher education’s top brass.

Even ministers have got in on the act. In the annual grant letter sent in March to the Higher Education Funding Council for England, the business secretary, Sajid Javid, and the minister for universities and science, Jo Johnson, said that they were “concerned about the upward drift in salaries of some top management” and they called for “much greater restraint”.

Almost one in five universities in this year’s Times Higher Education pay survey – the most comprehensive round-up of executive compensation in the sector – paid their leaders 10 per cent more in 2014‑15 than they did in the previous year. Overall, at roughly two-thirds of UK higher education institutions – 98 of the 159 surveyed by the accountancy firm Grant Thornton – the cost of the vice-chancellor’s office rose by more than the 2 per cent national increase handed to rank-and-file staff that year.

The average salary and benefits package paid to university heads rose by £14,595 to £252,745 in 2014-15, a rise of 6.1 per cent. When pension contributions are included, average remuneration was £274,405, which is 5.4 per cent higher than in 2013‑14. The median total payout was £268,500.

One of the highest increases last year went to Anne Carlisle, vice-chancellor of Falmouth University, which, with about 4,200 students, is one of the country’s smallest universities. Her overall remuneration rose by £57,391 to £285,900 in 2014-15, a 25.1 per cent rise, which takes her pay close to that of those running much larger and more prestigious institutions. For instance, it was more than the £271,000 paid to Sir Timothy O’Shea, principal and vice-chancellor of the University of Edinburgh (which has 35,500 students), and close to the total remuneration of £296,000 paid to Dame Nancy Rothwell, vice-chancellor of the University of Manchester (which has 38,600 students).

A Falmouth spokesman says that Carlisle’s remuneration was a “reflection of the continued growth and success of the university”, whose student numbers have grown by 30 per cent in the past two years. Student satisfaction and graduate employment have also risen steadily over the past four years, and Falmouth was judged by The Sunday Times to be the UK’s top arts university in 2015 and 2016, he adds.

Another university head to pick up a substantial pay rise was Geoff Layer, vice-chancellor of the University of Wolverhampton (which has 21,700 students). His total remuneration increased by 19.6 per cent to £268,000. Simon Walford, chair of Wolverhampton’s board of governors, says Layer’s remuneration reflects “the size, complexity and performance of our university”, as well as Layer’s “exceptional leadership” since joining in 2011, during which time he has consistently met “challenging targets and performance indicators”.

Enter your university’s name in the box to see how your v-c’s salary compares to institutional performance

More universities are now using performance-related pay or bonuses to form part of their vice-chancellor’s remuneration compared with just a few years ago, according to Richard Shaw, head of education at Grant Thornton. And he predicts a further rise, adding that it is important for remuneration committees to “make sure they are setting the right targets” to incentivise good performance. “If someone can help an institution achieve financial sustainability and growth, improve its research record, keep academics happy and produce good student satisfaction scores, why shouldn’t they be remunerated appropriately?” he says.

Sally Hunt, the UCU’s general secretary, says that it is “unacceptable for university leaders to continue enjoying bumper pay rises while failing to address issues around workforce casualisation, the gender pay gap and a real-terms drop in staff salaries of 15 per cent since 2009”. The gap between staff and vice-chancellor salaries has grown “embarrassingly large” and is “growing year-on-year” despite the “clear call from the government for pay restraint at the top”, Hunt adds. According to THE’s analysis, the average vice-chancellor now earns 5.1 times the salary of the average academic, excluding pension contributions.

Some of the largest year-on-year pay rises reflect large one-off payments to departing vice-chancellors. For instance, Michael Driscoll collected pay, benefits and pension worth almost £600,000 in his final year as vice-chancellor of Middlesex University in June, having led the institution for almost two decades. In addition to a £286,000 basic salary and £54,000 in benefits in kind, Driscoll received an extra £229,000 in cash and an additional estimated £24,000 in non-cash benefits as compensation for loss of office after he agreed to retire four months earlier than planned. That early departure enabled a “smooth transition” in leadership that was “essential for both the university and the students” and allowed Tim Blackman to take over as vice-chancellor in July, a Middlesex spokeswoman says. The payment was unanimously agreed by the remuneration committee and reflected Driscoll’s earlier-than-planned retirement and “long service to Middlesex”.

Such payments were fairly common last year, with 18 heads of institutions leaving at some point in 2014-15, often with a hefty sum in their pockets, our survey indicates. Martin Hall, for instance, was paid £110,000 in “compensation for loss of office” after his sudden departure in December 2014 as vice-chancellor of the University of Salford, as well as £30,000 in “relocation costs” for his return to his native South Africa and £121,000 in salary while he was on sabbatical for the first six months of 2015. All that took his total emoluments to £394,000, compared with £252,000 in 2013‑14. Costs for his replacement, Helen Marshall, lifted the overall bill for the vice-chancellor’s office to £516,000 in 2014‑15.

At Glyndwr University, the cost of the vice-chancellor’s office also doubled in 2014-15, to £490,983, after Michael Scott took leave of absence “to pursue research and other academic activities” in January 2015 and then stepped down as vice-chancellor at the end of March. Some £301,548 was paid to Scott that year, including £155,802 provided in lieu of notice, while the interim vice-chancellor, Graham Upton, cost an additional £189,435.

The changing of the guard at Durham University was also expensive, with outgoing vice-chancellor Christopher Higgins receiving his full salary up to June 2015, as well as £82,000 “at the conclusion of his role as an ambassador for the university”, despite his having moved to a pro-chancellor’s role in October 2014. This meant that his total package was £350,000, compared with £287,000 the previous year. With interim vice-chancellor Ray Hudson also paid £243,000, the total cost of office came to £593,000 in 2014‑15.

Overall, average salaries and benefits rose by 6.1 per cent between 2013‑14 and 2014‑15, according to Grant Thornton’s analysis, while the average total cost of office, including pensions, rose by 5.4 per cent. If analysis is restricted to the 117 institutions that have had no change in vice-chancellor over the previous two years, thus removing the effect of large one-off payouts, the rise in cost of office was 5.1 per cent before pensions and 4.3 per cent including them. That is significantly higher than the 3 per cent average rise calculated by a UCU report in February, which did not have complete figures for the sector.

Durham, Middlesex, Salford and Glyndwr account for the top four places in a ranking of the largest total payment on vice-chancellors in 2014‑15. The highest payment to a single leader was the £462,000 that the University of Oxford paid to its former vice-chancellor Andrew Hamilton.

Top 10 UK vice-chancellors by total remuneration

| Institution | Incumbent v-c | Total cost of office 2014-15 (£) | |

| 1 | Durham University | C. Higgins/R. Hudson | 593,000 |

| 2 | Middlesex University | M. Driscoll/T. Blackman | 591,000 |

| 3 | University of Salford | M. Hall/H. Marshall | 516,000 |

| 4 | Glyndwr University | M. Scott/G. Upton | 490,983 |

| 5 | University of Oxford | A. Hamilton | 462,000 |

| 6 | Plymouth University | W. Purcell/D. Coslett | 459,667 |

| 7 | King’s College London | E. Byrne | 458,000 |

| 8 | London Business School | A. Likierman | 431,000 |

| 9 | Imperial College London | K. O’Nions/A. Gast | 430,000 |

| 10 | University of Birmingham | D. Eastwood | 416,000 |

The sizeable cost of vice-chancellor departures is, to some extent, inevitable, according to David Palfreyman, director of the Oxford Centre for Higher Education Policy Studies. “Dumping vice-chancellors, chief executives or even football club managers will always see pay-offs happen – no chief executive simply leaves suddenly without a golden parachute. Governors simply behave as they would when moving on a chief executive in a business environment,” he says.

But the latest Hefce grant letter says that the sector should “review its guidance on severance payments”, and the use of “quasi-public money” to fund generous pay-offs may now invite more scrutiny, perhaps via the National Audit Office in extreme cases, Palfreyman believes.

“The days of paying people off so freely are probably over,” predicts Michael Shattock, visiting professor at the UCL Institute of Education. “That sentence in the grant letter [on severance payments] signals to governing bodies that they are now restricted in how they deal with these situations.”

John Rushforth, executive secretary of the Committee of University Chairs, says that the “most important” criterion of any severance package is that it is “in the best interests of the institution”. Universities must be “mindful both of their contractual obligations and of other advice”, notably from Hefce.

On setting vice-chancellors’ pay, Rushforth says: “Decisions are made by independent remuneration committees established by the governing body of each individual institution,” adding that institutions are becoming “more transparent about the principles and guidelines for setting remuneration”. Year-on-year comparisons of pay awarded to vice-chancellors were likely to be “distorted by many factors, including staff turnover”, with the committee’s internal data on pay rises to institutional heads suggesting a sub-3 per cent rise, Rushforth adds.

The average pay rise awarded to institutional heads in 2014-15 was actually slightly lower than the pay increase handed to rank-and-file staff, the Universities and Colleges Employers Association contends in a statement. That is because, in addition to the 2 per cent national pay increase, many staff also received progression and merit pay worth 1.5 per cent on average, adding up to a 3.5 per cent boost overall: “comparable” to the 3.3 per cent rise, as measured by the Higher Education Statistics Agency, awarded to vice-chancellors.

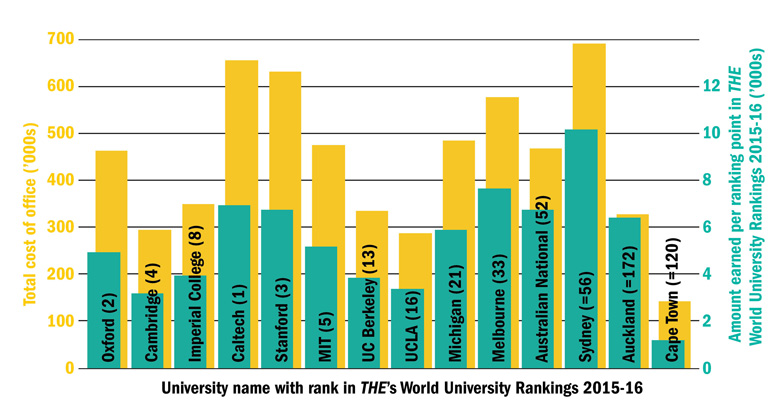

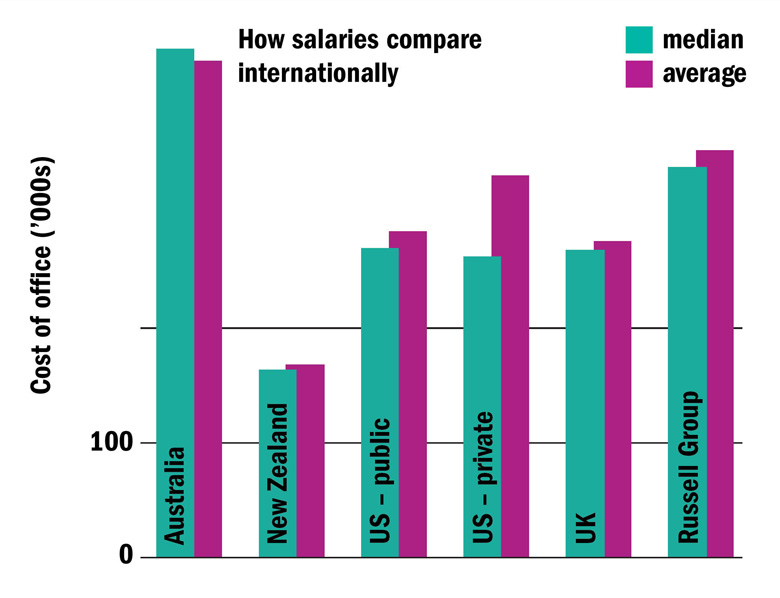

Despite such rebuttals, questions about executive pay in higher education refuse to go away. So are UK vicechancellors really overpaid? One way to answer this question is to compare their pay with that of university leaders in comparable countries, such as the US, Australia and New Zealand, where salary information is commonly disclosed. Making the right point of comparison is, of course, tricky, but our analysis suggests that UK vice-chancellors are not overpaid by international standards. Their salaries considerably outstrip those of their peers in New Zealand and South Africa, but are considerably below those of Australian vice-chancellors – who look particularly overpaid when their salaries are set against the performance of their institutions in THE’s World University Rankings.

UK salaries are also comparable to those of most presidents of US universities (see graph). However, top earners in the US can earn considerably more than their peers in the UK. A case in point is Andrew Hamilton. He was the highest-earning UK vice-chancellor in 2014‑15, collecting a total of £462,000, before he left Oxford to take over at New York University at the beginning of this year. But, according to The Chronicle of Higher Education, his predecessor in that post, John Sexton, earned a total of $1,452,992 (£994,800) in 2013. Even that placed him only 11th in a ranking of top earners at private US universities: leading that list was Lee Bollinger of Columbia University, who took home $4,615,230.

The top quartile by pay of private university leaders in the US received a total of at least $549,054 (£378,850) in 2012. However, that is not a vast deal more than the average paid to the leaders of the 24 members of the Russell Group, whose average remuneration, including pension and benefits, was £356,317 in 2014-15. When salaries alone are considered, the average paid to Russell Group members was £328,302 – about £29,000 higher than the previous year. This compares with an average salary of A$1,020,000 (£540,000) at Australia’s elite Group of Eight research-intensives in 2014.

Salaries paid by top-ranked institutions internationally

Note: this graph lists the leader’s salary at the relative country’s top-ranked institutions in Times Higher Education’s World University Rankings

Wendy Piatt, the director general of the Russell Group, says that remuneration committees are “acutely aware that to continue the global success of [Russell Group] institutions, world-class leadership and academic talent are required” – a nod to the trend of recruiting internationally and offering globally competitive rates of pay. Indeed, a quarter of the group’s heads are now foreign-born, and several universities – including some outside the Russell Group – have turned to Australia (Surrey, Anglia Ruskin, Ulster University) or the US (the London School of Economics, Imperial College London) to recruit their vice-chancellors in recent years.

Ed Byrne, who took over as president and principal of King’s College London in September 2014, is an example of how the race for global academic talent has fuelled pay inflation. His basic salary of £350,000 was £80,000 higher than that paid to his predecessor, Sir Rick Trainor, the previous year. When his £45,000 relocation package and £56,000 in pension contributions are included, Byrne’s £458,000 total remuneration deal is 41.1 per cent higher than Trainor’s was in 2013‑14. It takes him close to the A$1.045 million (£533,000) paid to him as head of Monash University, Australia’s largest higher education institution, in 2014.

Byrne’s remuneration reflects his leadership of a “large and complex organisation, with 26,500 students and nearly 6,900 staff…offices in Brazil, China, India and the US and an annual turnover in excess of £680 million”, says a King’s spokeswoman.

Bemoaning the large salaries commanded by university leaders reflects an outdated view of them as civil servants, believes Timothy Devinney, professor of university leadership at the University of Leeds. “These are very demanding jobs, running institutions of great complexity,” he says, adding that it is time to accept that there is a market for university leadership talent with certain salary expectations.

“If a mid-level marketing manager role in the City of London can be paid £200,000, why wouldn’t you pay the vice-chancellor of the University of Oxford a much larger amount?” he asks. Senior academics entering leadership roles generally have to give up their research careers and move institutions – sacrifices that are built into the cost of recruiting top people, he adds. “Finding a good scientist to lead your institution is a lot harder and more expensive than finding a good manager to lead it.”

But Devinney, who worked in the US, Australia and Hong Kong before coming to Leeds, is sceptical about the idea that UK universities need to keep pace with US or Australian executive salaries because mobility between university systems remains fairly limited.

“It’s a completely different way of working in US universities, which is why you don’t see many British academics becoming presidents or even deans in America,” he explains. “At my old university, the University of California, Los Angeles, there was a joke that if you saw the dean then they weren’t doing their job – they had to go out raising money because if they didn’t raise a couple of million dollars a year, the place didn’t run,” he says.

Some UK universities now want that type of externally facing president – hence a small number of US appointments. But Hamilton’s move Stateside is unlikely to herald a new trend given the lack of demand for UK-style academic leadership skills, Devinney predicts.

Philip Altbach, founding director of the Center for International Higher Education at Boston College, also believes that the “internationalisation” of university management is often overstated. “Top jobs in universities, in general, go to natives of the country,” he says. “There is only a very limited global market for top leadership. Unlike top professors, vice-chancellors in general cannot easily decamp to other countries.”

He suggests that higher salaries in the UK might be justified given the “growing corporatisation of British universities [and] the need to manage ever more complex financial arrangements” – but adds that many people in both the UK and the US feel that compensation is “getting out of hand”.

“It might be worth keeping in mind that the highest-paid employees of American universities are often the football and basketball coaches, earning double or more the salaries of presidents,” Altbach notes. “At least British universities do not have to look forward to that.”

Is UK pay too low to attract global talent?

Notes: US data are for 2012. Source: The Chronicle of Higher Education. Australian data are for 2014. Source: The Australian. New Zealand data are for 2014-15. Source: New Zealand State Services Commission. South African data are for 2014. Source: BusinessTech magazine

Does UK academia pay enough to attract and retain the brightest and best graduates?

While the 2 per cent pay rise awarded nationally in 2014‑15 was the highest salary hike enjoyed by university staff in five years, some within the sector are concerned that years of below-inflation rises and, from this April, the end of gold-plated pension schemes are making it hard to bring the nation’s brightest minds into higher education.

According to data commissioned from the Higher Education Statistics Agency by Times Higher Education, average salaries for full-time academic staff in 2014‑15 rose by just £622, up to an average of £49,082, a 1.3 per cent increase. (Hesa’s average pay rise figures differ from those published by the Universities and Colleges Employers Association because they include all staff, whereas Ucea focuses on those in post for at least 12 months.)

That was slightly less than the 1.8 per cent rise in average earnings seen in the UK in the year ended April 2015 – with take-home pay climbing by its biggest margin since the financial crash.

Timothy Devinney, university leadership chair and professor of international business at Leeds University Business School, believes that it is not enough, and describes the salary and benefits on offer to prospective academics as “mediocre”.

“You can make more money driving for Uber than you can being a lecturer,” Devinney says. He believes there should be a “rethink” of the structures that set academic pay.

“People like to think of academics as a bunch of nerds with bad clothes who look at their shoes when talking to you,” he says. “They’re not – these are really very talented people. You cannot keep indexing pay to the price index otherwise the top academic talent will go elsewhere.”

The UK’s higher education system was propped up by its ability to recruit top young academics from across the world, with less of the cream of the domestic crop considering a career in academia, Devinney says.

“Virtually every job candidate we interview is a foreigner, and hardly any PhD candidates are local – people are wondering if this is the 40-year career they want,” he says. “The only thing that makes the UK system able to work is its success in sucking in talent from countries with less mature higher education systems.”

At the higher end of the academic job market, things are a bit rosier. The average pay of a university professor in the UK rose by £1,795 to £78,190 in 2013‑14 – a 2.3 per cent uplift. For other senior academics, such as pro vice-chancellors and heads of school, there was a £3,091 increase to £82,321 – a 3.9 per cent increase.

“You have a whole range of pro vicechancellors whose salaries are ratcheted against vice-chancellors’ pay, so the gap between executive pay and general salaries has grown massively,” says Michael Shattock, visiting professor at the UCL Institute of Education. This is because vice-chancellors’ pay has “rocketed” while “everyone else is clamped in strict salary structures”.

A Ucea spokesman says that the latest Office for National Statistics figures show that higher education professionals earn a median salary of £48,709, which is £10,000 more on average than the national median for professionals.

“Out of the 71 professional occupations tracked by the ONS, higher education teaching professionals had the fifth highest median earnings in 2015.”

Ucea’s own workforce surveys confirmed that “the sector benefits from very few recruitment and retention difficulties, with the total reward package offered by higher education institutions competing well with packages in the private and public sectors,” he adds.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Princely sums

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?