The growth of international collaboration in the past decade has undeniably been an important driver of research progress in many nations and is likely to continue to be vital as the world emerges from the pandemic.

But the upper reaches of global university rankings are also littered with examples of pairs of institutions that are in close geographic proximity, suggesting that local collaboration continues to play a part too.

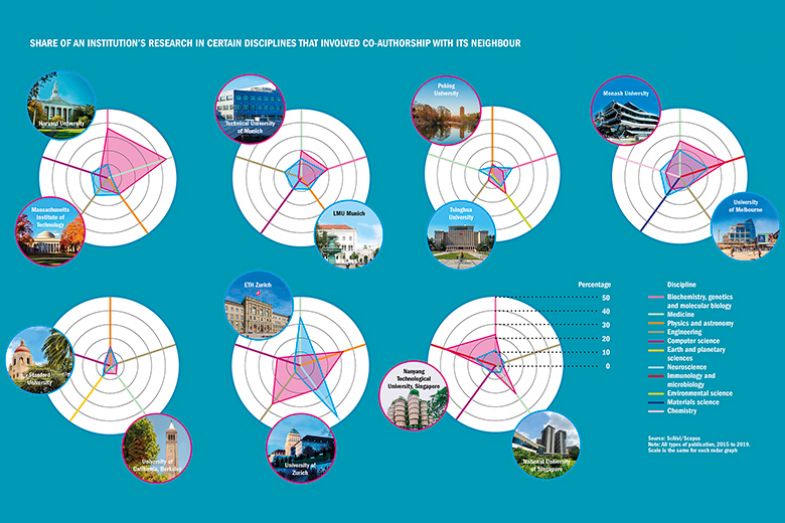

In the top 10 of the Times Higher Education World University Rankings, the most obvious example is Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which are little more than a stone’s throw from each other in the Boston suburb of Cambridge. Many other pairs in the top 100 share a city, and stretching the geographic proximity definition a little further to include city regions captures even more examples.

But to what extent do these institutions make a deliberate effort to work together in mutually beneficial ways, or is their cooperation simply based on their being part of ongoing global scientific collaboration in certain disciplines?

The broad data on inter-institutional collaboration for some of these universities – while not identifying specific bilateral tie-ups – appear to give some indication of which university pairings have stronger links, and in which disciplines.

For MIT, co-authorships that also include Harvard represent up to 45 per cent of its research output in some medical or life science disciplines, for example. On the flip side, Harvard collaborates relatively more as a proportion of its total output with MIT when it comes to computer science or engineering.

Similar patterns of collaboration can also be seen in some European pairings, such as ETH Zurich and the University of Zurich in Switzerland; and LMU Munich and the Technical University of Munich in Germany.

In Zurich, the trend is very clear with ETH seeing a high level of collaboration with its neighbour in areas such as medicine and neuroscience, while there seems to be a flow in the opposite direction for the physical sciences and computing.

Sybille Reichert, a consultant on higher education strategy who was head of strategic planning at ETH in the early 2000s, said that the universities had a close relationship, with regular leadership meetings and joint appointments in some research areas.

She said an example of such collaboration was ETH’s expertise in medical technology, such as imaging, combining with the clinical health expertise of the University of Zurich, something that led to growth at both institutions.

“If you have two good institutions that are internationally visible and look for fields where they have complementary strengths then you can build up something much more substantial,” she said.

Collaboration was also easier due to each institution “fishing in different ponds” when it came to research funding, with ETH being federally funded and Zurich being primarily funded by the local state, or canton.

Meanwhile, in Germany, she said that the “clusters” stream of the country’s excellence initiative meant there was an incentive for regional collaboration that often involved institutions in the same city.

Like Dr Reichert, Tatiana Fumasoli, director of the Centre for Higher Education Studies at UCL, said that the federal systems of government in both Switzerland and Germany helped such “functional diversity” to occur.

She added that both nations also shared a political culture that was more steeped in consultation and negotiation so that “competition never becomes life-threatening” for an institution.

“This means that higher education is conceived as an ecosystem where both competition and cooperation exist and contribute to overall system efficiency and effectiveness,” she said.

“This is quite different from countries with a more pronounced market economy, where higher education institutions have become primarily atomised competing actors that do not have a national/country sector-level perspective in their operations.”

Dr Reichert made similar points, adding that in a country like the UK, programmes such as the research excellence framework could sometimes lead to fierce competition for staff that might breed mistrust among universities.

However, she said that close collaboration between neighbours did have potential disadvantages, such as making them less nimble due to the lengthy communication and red tape that might need to be negotiated.

Some of the other university pairings in the rankings top 100 appear to have slightly different patterns of collaboration.

The two most successful Chinese universities, Tsinghua and Peking, both based in Beijing, broadly have lower levels of collaboration as a proportion of their research output but with some distinct areas – such as life sciences or environmental science – where one institution seems more reliant on cooperation than the other.

In Australia, collaboration between the University of Melbourne and Monash University is higher across the board but with areas of specialism at each institution standing out.

Singapore’s data, meanwhile, suggest that Nanyang Technological University collaborates more with its neighbour, the National University of Singapore, than vice versa.

One more curious case is the other two top 10 US universities that lie in geographic proximity, Stanford University and the University of California, Berkeley, although they are not nearly as closely located as their Boston counterparts.

The data do not offer such clear patterns here and overall co-authored publications are at a lower level.

Two US professors of economics with expertise on technology transfer – Al Link of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro and John Scott at Dartmouth College – said that inter-university collaboration in the US tended to be more discipline- or department-specific, rather than being organised at an institutional level.

More detailed analyses of bilateral co-authorship between institutions or co-owned patents might be needed to unearth whether stronger ties existed in some cases, they suggested.

A “serendipitous meeting at a conference that sparks a lifelong collaboration” was often more important than “geographic closeness”, said Professor Scott, although he added that “surely that often helps facilitate collaborations when interests are shared”.

Similarly, Bjørn Stensaker, director of the Centre for Learning, Innovation and Academic Development at the University of Oslo, said the links that could sometimes be seen between universities in many parts of the world often reflected the “close personal ties” of leaders and academics.

This made forcing institutions to work together from above a challenge because the partnerships then “run the risk of being ‘empty barrels’ – they are big, noisy, but empty” with academics unwilling to cooperate.

“To be successful here, you need to offer academics real advantages, for example, with respect to research opportunities,” he said.

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?