UK universities could lose leading research talent to rival European institutions in the wake of Brexit, senior figures believe, with Germany, the Netherlands and the Republic of Ireland among potential beneficiaries.

There is still no certainty as to whether the UK will remain inside the European Union’s research programmes post-Brexit by securing associated country status for research.

That raises the prospect that UK-based researchers could in future be unable to take part in the EU’s international research collaborations on societal challenges or its prestigious European Research Council grants for outstanding individual researchers, sometimes likened to “mini-Nobel prizes” or the “Champions League of research”.

Helga Nowotny, a former president of the ERC, said: “UK nationals, especially the younger ones, may seek employment elsewhere, especially in Germany. Language barriers on the Continent in academia are [being] rapidly lowered, and German research institutions and universities are keen to welcome the best younger researchers.”

She also warned: “I very much doubt that the UK will be able in the future to participate in the ERC competition, as it is tied to the principle of free movement of labour.”

Orla Feeley, vice-president for research, innovation and impact at University College Dublin, said: “We’ve had enquiries from UK-based academics post the referendum who are interested in relocating to University College Dublin. Obviously, we are entering into those discussions.”

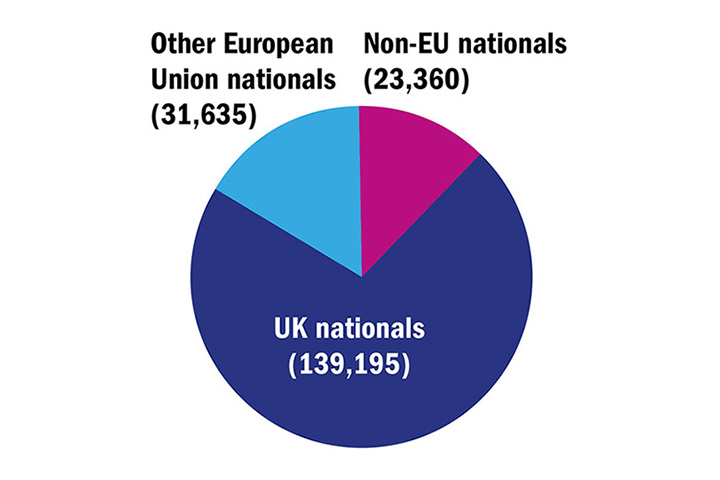

Number of academic staff in UK

Source: Hesa, 2014-15

The ERC, part of the EU’s current research programme, Horizon 2020, provided grants totalling about €12 million (£9.5 million) to Sir Andre Geim and Sir Konstantin Novoselov in their work developing graphene, according to the University of Manchester, where the Russian-born pair won a Nobel prize for their research.

ERC grant holders are required to spend at least 50 per cent of their working time in an EU member state or associated country.

Lord Rees, former president of the Royal Society, said: “I can certainly think of people who wouldn't be in UK universities were it not for the near unique benefits that these awards confer.”

He argues that it is “urgent” that the UK seek to remain inside Horizon 2020, the ERC and the EU’s Erasmus+ student and staff mobility programme.

Kurt Deketelaere, secretary general of the League of European Research Universities (Leru), said that “it is obvious that nobody with an ERC grant is going to stay in the UK” if the nation leaves EU research programmes.

Germany, whose leading institutions rank alongside UK counterparts in scoring the highest success rates in ERC grants (see table, below) and whose government-funded Excellence Initiative aims to make it a more attractive research location, would be one potential competitor for UK-based talent.

Top institutions for European Research Council funding by success rate

| Nation | Institution | Success rate % |

| Switzerland | ETH Zurich – Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich | 31.3 |

| Switzerland | École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne | 30.3 |

| Israel | Hebrew University of Jerusalem | 25.2 |

| UK | University of Cambridge | 25.0 |

| Switzerland | University of Geneva | 22.0 |

| UK | University of Oxford | 20.5 |

| Germany | LMU Munich | 19.0 |

| Germany | Heidelberg University | 17.9 |

| Switzerland | University of Zurich | 17.9 |

| UK | University College London | 17.6 |

| Germany | Technical University of Munich | 17.1 |

| UK | Imperial College London | 17.0 |

Source: European Research Council, 2007-13 figures, Framework Programme 7. Excluding research institutes, excluding universities with fewer than 100 bids evaluated

Georg Krawietz, London director of the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), an organisation funded by the federal government, said: “I think Germany, of course, could be a target country where Brits could look.”

But Dr Krawietz added that “neither the DAAD nor any other institution in Germany is looking at a kind of strategy…to attract, deliberately, Brits to come to Germany.” Instead, it was working with UK partners “to ensure the high level of research cooperation [between UK and German universities] is maintained”, he said.

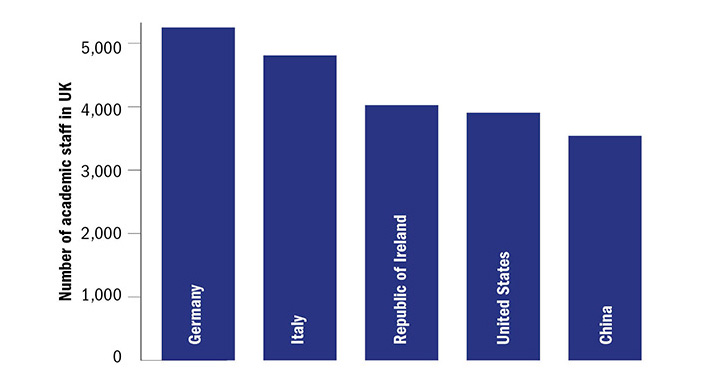

German nationals are the largest single non-British group among UK academic staff (see graph, below), accounting for 10 per cent of all foreign academics.

Dr Krawietz said that his office had received a small number of enquiries about relocation from German academics in the UK who were “concerned about their future” after the referendum vote.

“Particularly in the first weeks after the referendum, there was a feeling of not being welcomed any more, but this is not only applying to Germans but also to other EU scientists or researchers,” he added.

Jurgen Rienks, director of international relations at the Association of Universities in the Netherlands (VSNU), said that Dutch rectors are “very keen to continue working with UK universities – they are important partners for us”.

Top five nationalities for academics working in the UK

Source: Hesa, 2014-15 figures

He added that “Brexit aside…positioning yourself as universities in the wider international arena as an attractive working place for researchers takes a lot of effort”.

Any potential recruitment of international researchers in the wake of Brexit was “not something that our universities are aiming for right now – on the contrary,” he said. “But it will happen when it’s about individual researchers making a decision on where they want to go and where they want to work.”

Alistair Jarvis, Universities UK deputy chief executive, previously told Times Higher Education that it was a “distinct possibility” that the EU might seek to tie associated country status in research for the UK to the issue of free movement of people, as it has done with Switzerland.

Thomas Jorgensen, senior policy director at the European University Association (EUA), said: “There’s no legal link between single market access, the four freedoms and participation in Horizon 2020 or framework programmes.

“You could imagine a hard Brexit and [UK] association in the next framework programme. That’s not legally impossible. Is it politically possible? We have no idea.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?