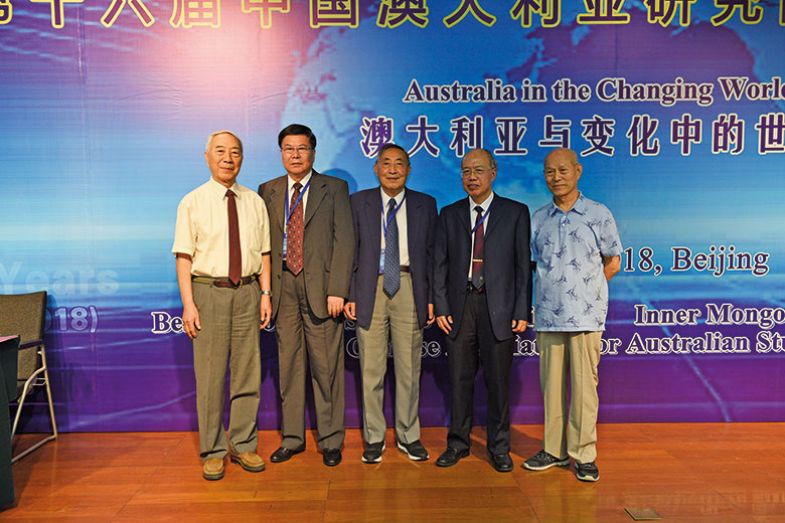

There is a tinge of sadness in the air as scholars young and old congregate in a sprawling industrial park on the outskirts of the ancient Chinese canal city of Suzhou for the seventh annual conference of the Foundation for Australian Studies in China (FASIC).

Du Ruiqing, a founding father of Australian studies in China and one of the first Chinese to leave the country’s shores under paramount leader Deng Xiaoping’s open door policy, had died just two days before. He was the youngest of the “Gang of Nine”, a group of middle-aged scholars who arrived at the University of Sydney in 1979, mere months after Deng announced the new policy, to study postgraduate literature and linguistics. When they returned home two years later, the group ignited a passion for Australian writing and culture throughout the Chinese academic community: they or their Chinese students were responsible for founding most of the 37 Australian studies centres that exist in China’s universities today.

The eulogies for Du expressed at the November conference reflect a deeply personal side to a bilateral relationship that is more usually viewed through a geopolitical lens. As the emergent superpower, China is front of mind in Australia – as elsewhere – and nowhere more than in the university sector.

Although there are only just over a third of the number of Confucius Institutes in Australia as there are Australian studies centres in China, the 13 university-based, Beijing-funded centres (a schools-based institute was recently axed by the New South Wales government) have become a particular source for concern. Critics claim that they are a front for Chinese spies and give Beijing a direct say in Australian university curricula.

Commentators also worry that the sheer numbers of Chinese students, whose tuition fees constitute more than one-quarter of some universities’ earnings, pose a direct threat to academic freedom. Media stories portray Chinese students flexing their muscles on a range of issues, including the positioning of China’s border with India, Beijing’s treatment of the Falun Gong spiritual movement and, most recently, autonomy for Hong Kong.

The alarm bells over Chinese-Australian research ties ring even more loudly. Sceptics say that Australia is subverting its own national and economic security by failing to safeguard its intellectual property or to ensure that joint research is not used for nefarious purposes, such as strengthening China’s military technology or its surveillance of Uighurs in Xinjiang province.

China has been implicated in major cyberattacks on Australian institutions, including the Australian National University (ANU) in Canberra, apparently in a bid to access defence research, and some commentators advocate that Australian universities should avoid dealing with Chinese universities or companies linked to the military or surveillance, such as technology giant Huawei. They also urge Australian academics to steer clear of collaborative research in fields with potential military applications, such as quantum computing, hypersonics and unmanned systems.

Others say that such fields are too broad to meaningfully enforce a ban on joint research, and that any restrictions should be confined to subfields where specific concerns have been raised. Meanwhile, advocates of engagement with China insist that Australia has more to gain than to lose from research partnerships in areas such as artificial intelligence and 5G communications, where Chinese universities and companies are acknowledged world leaders.

Advocates also highlight Australia’s research dependence on China, which is a vital fount of doctoral students and is rapidly overhauling the US as the top source country for international co-authors of Australia’s scientific papers. Any blanket ban on research collaborations with China risks crippling research Down Under, they warn.

Similar conflicts are playing out in the UK and the US. As part of an FBI crackdown on campus-based espionage, the National Institutes of Health is investigating almost 200 scientists – mostly Chinese – for violations such as not reporting external research affiliations. Former presidential aspirant Marco Rubio has led a campaign of investigations against the country’s 100-odd Confucius Institutes, while the government has reportedly cancelled or obstructed visas for hundreds of Chinese scholars.

The existence in China of 37 Australian studies centres – partly funded by the Australian government (see box) – suggests that the direction of influence between Australia and China is not all one way, however. And the mood at the centres’ annual conference suggests that notwithstanding the desire among some politicians and intelligence analysts to water down Sino-Australian academic ties, this will be no easy task.

For Li Jianjun, secretary general of the Chinese Association for Australian Studies, the year he spent at Queensland’s Griffith University in 2002 – his first overseas sojourn – was made memorable by the local academics who supported him and kept in touch after his return. That “emotional attachment” intensifies with every trip back and is immune to geopolitical squabbles, Li says: “This kind of contact is steel-capped.”

Li is also director of the Australian Studies Centre at the Beijing Foreign Studies University (BFSU), which he joined as an English teacher in 1998 after completing his master’s thesis on Paradise Lost. He initially aimed to continue researching British literature, but his plans changed when he was tapped on the shoulder by Hu Wenzhong, the Gang of Nine’s acknowledged leader, who had founded the centre in 1983.

“He was going to retire,” Li says. “The centre needed a person to take over.” Ever since, Li has taught courses including “Australian great books” and “the history of Australian literature”, while his current research focuses on Australian authors who were translated into Chinese during the 1950s and 1960s.

In his view, there is a simple reason why considerable numbers of Chinese scholars have gravitated to the works of Australia’s Peter Carey, Thomas Keneally, David Williamson and the like. “It’s mainly because of the influence of the Gang of Nine.” The Australian studies centres that they established were maintained by students who “stayed on after graduation and continued to teach, even after their teachers retired”.

This viral appetite for Australian literature – something rarely on display back home in Australia – was evident in the famously chilly north-eastern city of Harbin in May 2017. Of the four or five Australian authors invited for Australian Writers Week, Schindler’s Ark author Keneally was the only one to accept. However, more than 500 locals came to hear the author of the source work for Steven Spielberg’s Oscar-winning Schindler’s List, according to Li Jingyan, executive director of the Australian Studies Centre at Harbin Institute of Technology. “He was fascinated by the size of the audience and our thirst for knowledge,” she says. “We were impressed by his courage and eloquence. I overheard a student say: ‘A short, loving man from the other end of the globe suddenly became a giant in my mind.’”

Some Chinese knew nothing of the great southern land – beyond kangaroos, koalas and black swans – before becoming converts to Australian literature. Budding translator Li Yao, who graduated from Inner Mongolia Normal University during the Cultural Revolution, struggled to find anything to translate until a visiting University of Western Australia academic chanced upon him in 1978. She gave him a pile of Australian books, including Patrick White’s The Tree of Man and a selection of short stories by the bush poet Henry Lawson. It was the start of an illustrious career that has seen Li Yao, now a visiting professor at BFSU, translate books by dozens of Australian authors.

China’s early interest in Australian literature focused on post-war communist writers and left-leaning luminaries such as Lawson, seen as a voice of the working people. But Li Yao says it is now fuelled by a local fascination with Aboriginal Australia, particularly among Chinese minority groups, and a desire to learn more about the experiences of Chinese immigrants in colonial Australia (White’s great-grandfather came from Guangdong).

Australia has also supplied its share of elder statesmen for the literature love-in embodied in the Australian studies centres. They include historians David Walker and Colin Mackerras, both of whom are in attendance at FASIC 7.

Mackerras first visited China in 1964, a friend having alerted him to teaching opportunities there after he had completed a master’s degree on Chinese history. “It was purely accidental,” he says. “It wasn’t planned at all.”

He returned in 1973, shortly after Canberra established diplomatic relations with Beijing, and again with a group from Griffith in 1977. He has been back almost every year since, teaching at BFSU and nearby Renmin University since his retirement from Griffith in 2005.

“I think I’ve helped in improving Sino-Australian relations, but my story is mainly personal,” he says. But he laments the decline in bilateral relations caused by the “poisonous” debate about China that Australia is currently having.

“China wants to increase its influence in Australia,” he concedes. “It wants to increase its influence in a lot of places. Whether it’s a strategic threat, I really doubt. It’s certainly no more a threat than the US.”

Kee Pookong, convener of FASIC 7 by virtue of his role as BHP chair of Australian studies at Peking University, is keen to “try something different” by including more political discussion in the event and broadening its focus beyond humanities to science and technology. And the increasing attention on Australia’s scientific and technological relationships with China, highlighted in November’s release of guidelines to combat foreign influence on Australian campuses, makes this new focus “all the more relevant”, he says.

Paul Burrows, vice-president of the Jiangsu Industrial Technology Research Institute in Nanjing, describes a drug inhaling device and a system for driverless vehicles developed in collaboration with Melbourne’s Monash University. “At a national level, politics comes into play and countries get into arguments,” he says. “But at the…organisation level, my experience is that you almost always find people that just want to work together to solve problems.”

Ben Aldham, the country coordinator for China at Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), says China was the agency’s sixth biggest collaboration partner a decade ago in terms of internationally co-authored publications. Now, on that measure, it has just overtaken the US to claim top spot.

Aldham outlines the six research “challenges” attracting an increasing proportion of the CSIRO’s budget: the environment, food security, health, future industries, sustainable energy and regional security. “We are focusing on the issues that matter most to quality of life, the economy and the environment. As an organisation, we can’t grow our people count, but we can certainly collaborate more. Addressing these challenges will be a networked solution,” he says.

And, for all the political tensions, China seems likely to continue to play an important role in that network. Gu Min, executive chancellor of the University of Shanghai for Science and Technology, spent 31 years in Australia at five Sydney and Melbourne universities before returning to his native China in 2018. Now his research unites Australia’s research strength in photonics with Shanghai’s prowess in AI. The goal is to drastically reduce the enormous energy consumption involved in controlling autonomous vehicles, for example, by harnessing the “interface between AI and nano-optics. I believe that we can provide much better AI,” Gu tells the conference. “Much greener. Safer.”

Meanwhile, Edward Bertram, executive officer of the ANU’s China-Australia Centre for Personalised Immunology, says China’s huge population “gives us access to patients that we just couldn’t find in Australia”. The centre is studying rare diseases, looking for opportunities to develop new drugs or repurpose existing ones. Its partner, Shanghai’s Renji Hospital, has access to 60 families with paediatric lupus – a sample that would be “almost impossible to get in Australia”, Bertram says. “When you’ve got a rare disease, and every patient may have a different mutation in a different gene, it’s good to have at least two separate families that have the affected gene so that you can prove causation…If you want to help as many patients as you can, you need to get as many people involved as possible. It’s about sharing that knowledge.”

The discussion in Suzhou shifts back to literature as the conference reconvenes to launch two new books. One is Walker’s Stranded Nation: White Australia in an Asian Region, which explores the evolution of Australia's engagement with Asia in the 20th century; the other is Li Yao’s Australia’s China, a series of translations, featuring works about China by Australian authors.

Master of ceremonies David Carter, an emeritus professor at the University of Queensland, says the two books prove that Australia and China’s shared history is “far more complex than many Australians realise – and than many Chinese people, even within the Australian studies community, realise”.

But Chen Hong, director of the Australian Studies Centre at East China Normal University in Shanghai, tells the conference that the two countries are currently in “some kind of stranded relationship, which we cannot let continue”.

Chen has a complicated relationship with Australia. On the one hand, he is an aficionado, having reportedly been introduced to Australian studies by Gang of Niner Huang Yuanshen. Chen did his PhD on White, visited Australia in 1991 at the invitation of former prime minister Gough Whitlam and was on hand to do the translating when later prime minister Bob Hawke visited China in 1994.

On the other hand, Chen is one of Australia’s most trenchant critics, regularly castigating the country in the Global Times – a daily tabloid published by the state-owned People’s Daily – for its “obsessive paranoia” about China. He tells the conference that New South Wales’ recent decision to close its Confucius Classrooms programme was “disappointing and deplorable”. Observing that Confucius Institutes only teach language, calligraphy and dancing, as well as organising language festivals and public speaking contests, he asks: “How could anyone be afraid of Confucius Institutes? No one in China is afraid of FASIC. I wonder if the Adelaide Zoo will one day banish the pandas as agents of cultural intrusion.”

He attributes Australia’s current concerns about China to US-derived “political prejudices” rather than racial motives, and dismisses “the anti-China camp in Australia” as “a small cluster of extremists…who work closely with elements, especially in Washington, attempting to block China’s peaceful development”.

Australian China critics often accuse the Australia-China Relations Institute at the University of Technology Sydney of being in the pocket of Beijing and pursuing an excessively uncritical line on China. The centre’s director, James Laurenceson, compliments the conference for promoting “upbeat examples” of scientific collaboration between the two countries. But he warns delegates against ignoring the “complicated” political and media environment.

“Folks, you’ve got to grapple with these headlines,” he says. “You can’t pretend they don’t exist and just talk about positive case studies. If you do that, we will be steamrolled as a sector and that collaboration – that wonderful increase in joint knowledge creation we’ve seen over the last decade – is going to take a hit.”

Laurenceson cites newspaper articles linking Australian research on surveillance with the repression of Turkic-speaking minorities in Xinjiang. “I can tell you, no Australian university wants anything to do with what’s happening in a place like Xinjiang today. It’s absolutely contrary to core Australian academic values, and Australian universities don’t want their research contributing to it.”

But if Australia were to follow the US in “a technological decoupling from China”, he adds, it would risk not having access to the world’s best technology for the first time in its history. “While it’s absolutely legitimate that we have concerns over specific research collaborations, that’s a big-picture question that Australia has to grapple with. I’m concerned [that] because the geopolitics has shifted, universities may almost self-censor and not engage, in part because of treatment in the media [that] often misses the big context.”

As the conference closes, three stories about the Australia-China relationship are doing the rounds of Australian media. One concerns allegations that a Chinese agency unsuccessfully attempted to plant in the federal parliament a Chinese-Australian car dealer, who was subsequently found dead in mysterious circumstances.

Meanwhile, a self-proclaimed spy and asylum seeker appears on television claiming that Beijing ordered overseas assassinations, including in Australia, while a consortium of investigative journalists unearths documents demonstrating that Chinese authorities “red-flagged” 23 Australian citizens for detention in Xinjiang.

A fourth story, directly concerning universities in both countries, is about to break. An Australian security thinktank has developed a “tracker” database outlining the covert military links of some 160 Chinese institutions, including many of the country’s top-ranked universities. Thirteen of them host Australian studies centres.

Will the Sino-Australian emotional ties that spawned those centres be enough to sustain the vibrant academic interchange they embody amid such a geopolitical battering? Only time will tell. But one thing is clear: there is a gang of many more than nine that will do everything they can to ensure that the links endure.

john.ross@timeshighereducation.com

Windows on another world: Australian studies centres and Confucius Institutes

Unlike the Confucius Institutes, which are part of China’s soft power drive, the Australian studies centres in Chinese universities were developed spontaneously by returned scholars.

The centres offer courses on Australian culture, society and history at the undergraduate and postgraduate level. Their subject matter ranges from Australian literature, language and cinema to politics, foreign policy, economy, trade, women’s issues, Indigenous Australian studies and China-Australia relations.

The centres have helped to sustain a thriving translation effort, with dozens of works of contemporary and historical fiction and non-fiction from both countries rendered in each other’s tongues. Most of the centres are located in their universities’ schools of English or literature, but some reside in education, journalism or international economics and business departments.

While the centres are administered and financed by their host institutions, they have been receiving some Australian government funding through the Australia-China Council – an arm of Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade – for more than two decades. The council is being replaced this year by a new National Foundation for Australia-China Relations.

Support for the centres also comes from the Foundation for Australian Studies in China (FASIC), an independent non-profit body established in 2011 by the Australia-China Council, Australian mining giant BHP, the Australian Department of Education and Universities Australia.

Through the Australian Studies in China programme, which it has managed since 2016, FASIC funds scholarships for both Australian and Chinese students. It also supports Australia-focused research projects and the dissemination of their findings through publications and conferences.

Similarly, Confucius Institutes are not-for-profit bodies focused on promoting Chinese language and culture in Australia and around the world. But they differ from Australian studies centres in both structure and funding.

They operate as three-way partnerships between the local host institution, a supporting Chinese university or education agency and the Confucius Institute Headquarters at Hanban, a Beijing-based offshoot of China’s Education Ministry, responsible for promoting the teaching and learning of Chinese language internationally. The institutes are overseen by boards with representation from both the host institution and the Chinese partner, sometimes also including other local academics or community figures.

While Hanban does not directly manage the institutes, it usually provides about half their funding, along with financial oversight and some administrative support, staff and teaching resources. Many institutes also source staff and teaching materials locally.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Never mind the political weather

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?