The recent attacks by Islamic terrorists in Paris and San Bernadino, California have once again focused feverish political attention on measures to prevent radicalisation.

The attacks came shortly after UK universities became subject to the Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015, which controversially obliges academics to monitor students for signs of radicalisation. Universities are also required to deny a platform to radical speakers unless the risk of audience members being drawn into terrorism can be “fully mitigated”. By 22 January, English universities must submit a self-assessment of their level of preparedness to comply with their new duties to the Higher Education Funding Council for England. Last week, the Daily Mail ran a front-page exposé claiming that up to 19 universities “could face” investigation after giving an “unchallenged platform” to an organisation that allegedly sympathises with Islamic terrorists.

But are universities really incubators of radicalism? And are the Prevent requirements proportionate and workable? Will they have the desired effect? And how do they compare with the approaches of other countries? We ask a range of experts to give us their views.

A legal scholar’s view of the Prevent obligations

Precisely what are ‘British values’? This lack of certainty would likely be fatal to the legality of the measures under European law. It might also fail the separate test of proportionality

I recently spoke in support of free speech at a meeting of a student atheism society in London. In hindsight, I wonder how I was ever permitted to be let loose upon impressionable young minds.

For some time now, the UK government has felt that universities and colleges are not doing enough to disrupt attempts to radicalise students. In 2011, the previous independent reviewer of terrorism legislation, Lord Carlile of Berriew, claimed in his Report to the Home Secretary of Independent Oversight of Prevent Review and Strategy that “universities have been slow or even reluctant to recognise their full responsibilities”.

The Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015 places a legal duty on listed authorities, including universities, to have “due regard to the need to prevent people being drawn into terrorism”. Failure to comply could render vice-chancellors in contempt of court. The government’s guidance on implementing the act also mentions “non-violent extremism”, this being thought responsible for the creation of “an atmosphere conducive to terrorism”. “Extremism” is defined as “vocal or active opposition to fundamental British values, including democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty and mutual respect and tolerance of different faiths and beliefs”.

It should also be said that the act instructs the home secretary, when she issues such guidance, to have “particular regard” to “freedom of speech” and “academic freedom”. Before the general election in May 2015, internal divisions within the coalition government halted a version of the guidance that would have expected universities to carry out stringent checks on visiting speakers, and obliged students’ unions to give universities 14 days’ notice to allow for background checks and, if necessary, cancellation of speaking events. But the revised guidance, issued in September 2015, stipulates that meetings to which “non-violent extremists” have been invited are now to be allowed to go ahead only if they are also addressed by another speaker who challenges the “extremist”. The meeting should be banned if there is any concern that the risk of “drawing people into terrorism” cannot be “fully mitigated”.

While this approach is less objectionable in principle than an outright ban on controversial speakers, the uncertainty around the notion of a “non-violent extremist” may prompt student societies to select anodyne speakers who do not require a challenger.

Even Sir Peter Fahy, the chief constable of Greater Manchester Police, is on record as saying that the phrasing of the guidance gives the police too much discretion to decide, in the heat of the moment, what counts as extremism. Precisely what are “British values”, for example? Should a visiting speaker talking about Plato’s views on the desirability of rule by elite guardians be banned?

This lack of certainty would also, in all likelihood, be fatal to the legality of the measures under European Convention law, which requires that domestic restrictions on the right to freedom of expression be framed sufficiently clearly to allow people to regulate their conduct accordingly. It might also fail the separate test of proportionality; under the Human Rights Act 1998, a court in the UK could find that the new rules caught a range of speech forms (such as criticism of UK foreign policy) that did not threaten public order or public safety. In July 2014, no less a person than the current independent reviewer of terrorism legislation, David Anderson, said that the powers were too widely drawn and would catch people who have no intention of threatening or intimidating others.

Moreover, there already exists a range of legal controls on speakers, including laws on terrorism, public order and incitement to racial and religious hatred. By unnecessarily closing down free speech in universities, the government is handing the enemies of democracy a huge victory.

Ian Cram is professor of comparative constitutional law at the University of Leeds.

A terrorism researcher’s perspective

Allowing radical ideas to be aired freely and openly, so that they can be organically challenged and critiqued, is essential

Whenever terrorist attacks take place on the streets of a European city, one question is always asked: what drove them? The recent attacks in Paris are no exception. Before the total number of people killed had even been established, media pundits, “experts” and politicians quickly began asserting that the attacks had occurred because the terrorists, motivated by an irrational and evil ideology, hate “our” values and “our” way of life.

Such statements make for snappy soundbites and provide the West with a sense of its own superiority. However, they also dehistoricise the West’s own actions in the Global South and whitewash the contemporary role it has played in creating conditions that have given rise to groups such as Islamic State and al-Qaeda, and that has prompted a small number of European nationals to undertake armed attacks at home and abroad.

Understanding and representing the political Islamic opponent in such a way is not without consequence. It dictates the nature and types of policies that are introduced to deal with terrorism and political violence. In the UK’s Prevent “deradicalisation” strategy, “extremist ideology” is claimed to be the main driver of terrorism. Since the Conservatives came to power in 2010, this idea has gained significant traction because of the influence of neoconservative thinktanks and self-styled former extremists, who argue that politicised interpretations of Islamic theology (“Islamism”) are causing terrorism.

Prevent has therefore been structured to disrupt the ability of institutions such as universities to provide a platform to alleged terrorist sympathisers and extremist ideologues. In practice, “disruption” means questioning and interrogating postgraduate students such as Mohammed Umar Farooq, who was recently investigated by Staffordshire University for reading a textbook on terrorism for his master’s programme in counterterrorism, and the unnamed student at the University of East Anglia who was recently questioned by Special Branch officers after accessing course reading on IS that had been uploaded to the online portal Blackboard by his lecturer.

Ideology does not cause terrorism. Academics and counterterrorism practitioners across the board seem to accept that terrorism is caused, instead, by a series of socio-economic and political factors that intersect with one another. In essence, the existence of unjust and unfair socio-economic and political realities gives sanctity and legitimacy to an ideology that seeks to organise society in an alternative way – sometimes, but not always, through violence.

The creation of a legal duty on universities (and other public sector workers) to report extremists or “potential terrorists” therefore has a deeply damaging impact in so far as it creates a climate of fear and self-censorship. This undermines students’ ability to critically engage with contemporary and historical issues, especially within the social sciences.

Repressing a particular idea or viewpoint does not eradicate it. Instead, it drives it off radar, into spaces that are largely ungoverned and impenetrable to everybody except the intelligence services. These spaces serve as echo chambers, in which views and ideas are reinforced and strengthened, not challenged or questioned. So while the “disruption” of individuals and the closing-down of spaces at universities in which “extremists” are said to operate may seem like an appropriate approach to the general public, such a policy, in reality, will perpetuate the problem and reinforce the claim that Islam is under attack from a hypocritical government that suspends or selectively applies due process, human rights and “British values” when it comes to Muslims.

Authoritarian and repressive policies create an environment in which terrorism is viewed as being the only plausible way of bringing about a political or social change. The way to reduce the desire within individuals to engage in armed action is to deal with the socio-economic and political problems, both on the ground and structurally, and to stop the erosion of free speech and expression. Allowing radical ideas to be aired freely and openly, so that they can be organically challenged and critiqued, is essential. Rather than standing idly by while the government threatens legal penalty if they refuse to service the jingoistic policy that is Prevent, universities and academics should resist the policy and challenge the government’s attempts to securitise our campuses and muzzle free speech and expression.

Rizwaan Sabir is lecturer in criminology at Liverpool John Moores University and a researcher of counterterrorism and the UK “War on Terror”. His research was motivated by his false arrest and detention in 2008 under the Terrorism Act for possessing the al-Qaeda training manual that he was using for his postgraduate research on terrorism. In 2011, he secured damages totalling £20,000. He tweets at @RizwaanSabir.

The secularists’ view

British universities are censoring secularist and humanist intellectuals who express concern about the dangers of Islamism

In late September 2015, about 1,000 people packed Logan Hall on the campus of University College London for a panel discussion on “preventing Prevent”, organised by the students’ union at Soas, University of London.

The panel moderator was an advocate from the Islamic Human Rights Commission, a group that co-organises an annual march, “Day of Al Quds”, or “Day of Jerusalem”, which one year featured several marchers carrying signs reading “We are all Hezbollah”, in support of the militant Islamist group in Lebanon. The panel included former Guantanamo Bay detainee Moazzam Begg, the outreach director of the controversial organisation Cage, a group campaigning for the release of alleged and actual terrorist prisoners. Last year, Cage’s director Asim Qureshi expressed sympathy for Mohammed Emwazi, or “Jihadi John”, the Islamic State executioner reportedly killed by an American air strike in the days before the Paris attacks, claiming that the “kind” and “gentle” man had been radicalised by the “harassment” of the security services. In November, Begg returned to Soas to give a plenary speech at a conference, Policing the Crisis, amid the new legal requirements for universities to curb extremism on campus.

In a murky world of identity politics, the uncompromising fringes of ultraconservative, reactionary Muslim communities in the West are finding friends on the Left who, wittingly or unwittingly, help to promote a form of political Islam that seeks to establish a totalitarian state in which public policy is set by divine law, undermining the very nature of Western governance.

Such people exploit reasonable demands from alienated Muslims to try to silence the debate about Islam and its political variants. Working in tandem with efforts in the US, France and other countries, they act to defend the perceived honour of Islam, promoting a brand of their faith that is highly politicised and uncompromising, silencing debate on the religion through bullying, intimidation and claims of “Islamophobia”.

As Islamists rile vulnerable, disenfranchised Muslims against the West, the UK’s hands-off approach paves the way to a future of unbridled radicalism. Universities have played a key role in the spread of an ideology of active resistance to Western democracy and values by giving a platform to such speakers.

Compounding the problem, British universities are censoring secularist and humanist intellectuals who express concern about the dangers of Islamism. In late September, the students’ union at the University of Warwick cancelled a talk by Maryam Namazie, a secular Iranian-British former Muslim and human rights activist, alleging that she “could” incite violence with her criticism of Islamists. Appropriately, the union later reversed its decision and apologised, citing administrative errors, but only after a fierce social media backlash.

Squashing the right to publicly criticise reactionary Islamists and the pro-Islamist Left represents an institutional and societal failure to defend the very values that made the UK the cradle of the Enlightenment: democracy, liberalism, autonomy and human rights. It is a soft racism of lower expectations that excludes minority ethnic and religious groups from reasonable criticism.

We are facing a crisis on British campuses. Recent newspaper reporting reveals that the Islamic Student Society of the University of Westminster is dominated by ultraconservatives, some of whom are accused of discriminating against lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender students and refusing to talk to female Muslim university staff. In 2011, anti-extremism experts warned of the students’ union’s close affiliation with the Islamist group Hizb ut-Tahrir, which advocates for an Islamic caliphate, but their concerns have largely gone unheeded amid claims that the group continues to be active on UK campuses.

The involvement of Cage in university circles encapsulates the abject failure of laissez-faire university strategies. The organisation reputedly campaigns against the “War on Terror”, but the reality looks much murkier. Cage staff and volunteers have publicly endorsed violent jihad and associated with terrorists. Last year, Amnesty International finally severed ties with the organisation.

Still, in October, representatives of the National Union of Students toured five major UK universities with a nationwide campaign, “Students Not Suspects”, to oppose the Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015. While Megan Dunn, the NUS president, said that she had cut ties with Cage, about 100 student leaders protested the decision, and, at key rallies in London, Birmingham, Bradford and Manchester, NUS leaders and members spoke alongside Begg. Their aim is to resist security measures and to "counter ... the presence of the police on our campuses".

All this demonstrates that clear rules on campus are needed more than ever. Reactionary Islamists should not be empowered. Instead, they must be challenged with the same weapons normally used to deal with far-right groups.

Whether by ignorance or careful political planning, the NUS and its partners, the University and College Union and the Federation of Student Islamic Societies (which, according to newspaper reporting, has a history of giving a platform to Islamist extremists), have fed legitimate rights to criticise government policy into the mouths of Islamist propagandists who attempt to intimidate and silence critics.

In June, the University of Bath gave a platform to Begg and other controversial speakers, such as Deepa Kumar, a professor at Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, and Max Blumenthal, a bombastic anti-Israel writer, during a four-day academic conference. Academics from Bath later mounted an unconvincing defence of Cage on the Open Democracy website, declaring the organisation to be a defender of human rights.

According to data cited by the government, British universities gave a platform to hate preachers on at least 70 occasions in 2014. Although some universities have quibbled over that figure, it is clear from our own experience that that number is not unreasonable: highly divisive Islamists and Islamist supporters are slowly being mainstreamed at the expense of moderate Muslims. Aside from occasional debates between prominent Muslim speakers and secularists, which for the most part are theatrical and rhetorical artifices with little space for real dialogue, incendiary Islamist speakers take the stage at one-sided, large events with a clear ideological orientation and no space for moderate, contradictory views.

No matter what restrictions the government imposes on universities, as long as university and student leaders remain unwilling to combat anti-Muslim bigots and intolerant Islamists with the same weapons, British universities will continue to be a fertile ground for political ideologies that challenge the long-held liberties shared by the majority of society. We need to end these unholy alliances before it is too late.

Stefano Bonino is a lecturer in criminology at Northumbria University. Chris Moos is a teaching assistant at the London School of Economics and was a nominee for the Secularist of the Year 2014 award. Asra Q. Nomani is an investigative reporter and a former professor in the practice of journalism at Georgetown University in the US.

International comparisons

Expansions of anti-terrorism laws mean that it is easier than it used to be to run afoul of terrorism offences on campuses, but the focus should be on preventing violence, not extremism

The UK often sets the standard with counterterrorism laws and strategies. The new Prevent rules, introduced in September, are intensely and rightly controversial, and make the challenge of drawing lines between freedoms and counterterrorism duties particularly acute in UK universities.

Nevertheless, it would be a mistake to think that universities outside the UK do not face similar challenges. Post-9/11 expansions of anti-terrorism laws throughout the world mean that it is easier than it used to be to run afoul of terrorism offences on campuses.

Australia and Canada, for instance, instituted new offences in 2015 relating to the advocacy of terrorism. In Canada, this has already been challenged under the constitutional bill of rights, and the new Trudeau government is seriously considering its repeal. But even if the repeal happens, universities and students should recognise that campuses are not immune from the law. Hate speech laws apply on Canadian campuses. Even in the US, the First Amendment’s protection of freedom of speech does not shield campus activities from the scope of offences that target the material support of terrorism.

At the other extreme of the debate, however, governments should refrain from holding universities responsible for every student who commits terrorist crimes. This is not done for other offences and it does not recognise that university students are adults. The UK government’s claim to know that “at least 70 events took place featuring extremist speakers” sounds to my North American ears unnervingly akin to statements from Senator Joseph McCarthy in the 1950s about communists.

The UK’s increasing focus on extremism per se, as opposed to violent extremism, is problematic. The broad and vague requirement for universities to risk-assess non-violent extremism “which can create an atmosphere conducive to terrorism and can popularise views which terrorists can exploit” bites too deeply into the legitimate realm of free speech and academic freedom. It might, for instance, prevent presidential candidate Donald Trump from speaking at UK universities. We should have more confidence in the ability of university students to debate extremism.

Still, governments would be negligent if they did not have multidisciplinary programmes to target violent extremism. These can address causes of terrorism that were often ignored after 9/11. But this poses real challenges for federations such as Australia and Canada (where education and healthcare are within provincial or state jurisdiction) given that schoolteachers, childcare workers and health professionals are better placed than police, security officials or university officials to respond to violent extremism.

The focus of such programmes should be on preventing violence, not extremism. Moreover, the results of such new programmes should be subject to independent research because of the dangers that they may be poorly implemented, discriminatory and even counterproductive.

Academic freedom is a valuable resource and not a counterterrorism liability. Given the very real threat presented by Islamic State, university researchers need the freedom to conduct research. They need access to Islamic State websites and social media. Within the confines of ethics review and informed consent, they need access to those who may be attracted to IS’ abhorrent and violent ideology. Unfortunately, such important and socially useful research can be thwarted because of overbroad terrorism laws and programmes.

Kent Roach is a professor of law and Prichard-Wilson chair in law and public policy at the University of Toronto. His books include Comparative Counter-Terrorism Law and The 9/11 Effect, both published by Cambridge University Press. His latest book, co-written with Craig Forcese, is False Security: The Radicalization of Canadian Anti-Terrorism.

The academic freedom advocate

The real tragedy is not that there is too much in the way of clashing views on campuses but rather that there is too little

I have never experienced such an illiberal and censorious climate on campuses in the 50 years that I have spent in universities as a student and teacher. It seems that everybody wants to curb freedom of expression and exchange it for some alleged benefit. Many student activists call for trading off free speech for the right not to be offended. From their perspective, banning speakers is a small price to pay for immunising campuses from harmful speech. Now the government wants to trade off traditional freedoms, this time in exchange for defending national security.

Among the duties imposed on universities by the Prevent guidelines is a requirement to spot and report any student who may be “vulnerable to radicalisation”. At a time when the security services are struggling to comprehend what a home-grown terrorist looks like, the demand that university staff should be able to recognise them has the status of a fantasy. The further demand that behaviour associated with “non-violent extremism” should be curbed is particularly troubling. Students have always been drawn towards ideas that some consider extreme. Intellectual experimentation often leads towards radical ideas, and a tolerant and open society does not need to resort to repression to deal with it. The attempt to turn academics into amateur spies will have little consequence other than to undermine the trust between them and their students that is integral to an academic relationship.

The idea that a loss of freedom makes society more secure implicitly communicates a loss of conviction in the values of an open society. Yet these are precisely the values – freedom, tolerance, democracy – that provide the moral and political resources for mobilising opposition to the violent zealots who want to destroy a secular, enlightened society.

The policing of campus culture undermines the capacity of universities to provide students with the opportunity to gain clarity through the free exchange of opinion. Perversely, it also diminishes the moral authority of those who uphold the values of Enlightenment democracy against intolerant radical jihadist dogma.

The real tragedy is not that there is too much in the way of clashing views on campuses but rather that there is too little. Most people prefer to ignore radical Islamist sentiments. In an article in The Washington Post, Avinash Tharoor – a fellow student of Mohammed Emwazi, “Jihadi John”, at the University of Westminster – offered a far from rare example of the reluctance to challenge anti-democratic Islamist views. He recalled a seminar discussion in which a student wearing a niqab dismissed Kant’s democratic peace theory, arguing that “as a Muslim I don’t believe in democracy”. According to Tharoor, the seminar leader looked astonished, but “simply moved on”. It appears that it is easier to ban “hate preachers” than it is to confront the everyday arguments advanced against a democratic way of life.

This is the real danger facing campus life and wider society. When people feel that they cannot express themselves freely, it is the enemies of democracy who triumph. The ease with which the students’ union at University College London recently banned an anti-Islamic State speaker invited by its Kurdish Society exposes the casual way that freedom of speech is regarded on many campuses. Prevent guidance simply reinforces this dreadful trend. Exchanging freedom for security doesn’t make society more secure, but it diminishes the moral authority of democratic ideals.

Frank Furedi is emeritus professor of sociology at the University of Kent. His latest book, Power of Reading: From Socrates to Twitter, is published by Bloomsbury Press.

A historical perspective

Over 40 years the UK has adopted many counterterrorism measures, but the restrictions in the Prevent strategy are different from all prior measures

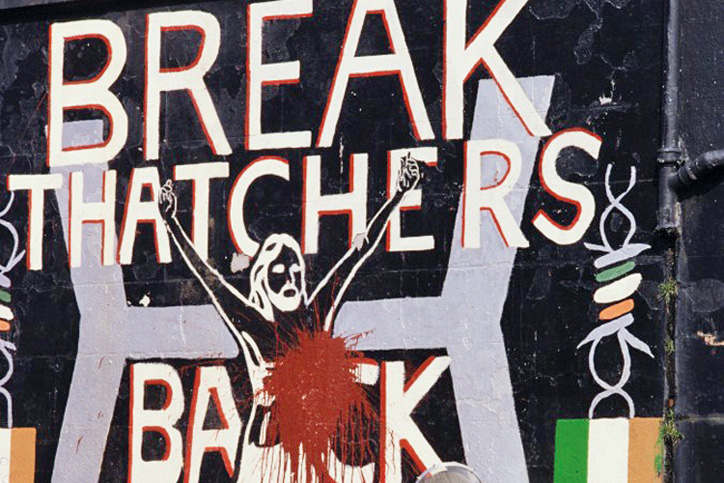

For more than four decades, the UK government has been dealing with a variety of terrorist threats, from Republican and Loyalist paramilitaries in Northern Ireland since the early 1970s, to international terrorists such as the Palestinian Liberation Organisation in the 1980s and 1990s, to the contemporary threat from Islamic terrorism. Hence, the Prevent strategy, first introduced in 2003 and placed on a statutory footing in February 2015, is just one in a long line of counterterrorism measures that the UK has adopted over the past 40 years.

In the early 1970s, legislation enabled the secretary of state to proscribe terrorist organisations in Northern Ireland. The effect of proscription was to make it a criminal offence to be a member of, associate with or address a meeting of that organisation. These restrictions were considered an essential, if primarily symbolic, means of curbing terrorist behaviour at a time when terrorism was killing more than 200 people a year in Northern Ireland.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the so-called Broadcasting Ban barred television and radio stations from airing interviews or statements from representatives of proscribed organisations or their affiliated – legal – political parties in Northern Ireland. Explicit censorship of this kind had not existed since the end of the Second World War.

The Broadcasting Ban was brought to an end in the mid-1990s, but the proscription regime has been retained into the 21st century. Its measures now apply to all types of terrorist organisation, including al-Qaeda and Islamic State. Other laws have made further inroads into the right to free speech and association. The Terrorism Act 2006 criminalised statements that encouraged terrorism, and the Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures Act (which replaced control orders in 2011) places restrictions on terrorist suspects’ freedom to associate or communicate with specified persons.

There is not much evaluation of how effective any of these measures were. Evidence about the value of proscription in Northern Ireland is mostly anecdotal, and the more recent laws have not been used enough to build up a body of evidence. But the restrictions on free speech and free association in the Prevent strategy are different from all these prior measures, which have all specifically targeted terrorist suspects. Prevent targets those whose behaviour is simply suspect.

The goal of preventing students from being drawn into terrorism is commendable, and some restrictions on free speech are justified in exchange for increased security. But the Prevent duty is drawn too broadly; it diverts into Channel, the UK’s deradicalisation programme, students who may have no intention of engaging in or inciting others to engage in violent, criminal or terrorist behaviour. In effect, the government is instituting a type of thoughtcrime, penalising people for what they believe, not the actions they take. This runs counter to the fundamental values of free expression that lie at the heart of the government’s counter-extremism agenda. In the wake of the recent terrorist attacks in Paris, therefore, we need more, not less, free speech on campus if we are to defeat extremism in all its forms.

Jessie Blackbourn is lecturer in politics at Kingston University.

Counterterrorism in Australia

The lack of formal requirements on unive rsities to prevent people being drawn into terrorism is one of the few admirable qualities of Australian counterterrorism efforts

The recent expansion of the Prevent strategy into UK universities reveals a worrying trend in counterterrorism, in which institutions and organisations outside the government are required to help identify young individuals who show signs of radicalisation.

Australia is yet to take such an approach to preventing terrorism, although it has taken just about every other approach available. Between 2002 and 2007, under the Howard government, the Australian parliament enacted more than 50 pieces of anti-terrorism legislation. This prolific lawmaking slowed under the Labor governments between 2007 and 2013, but has since been revived by the Liberal-National coalition.

Throughout 2014 and 2015, five tranches of national security legislation were introduced in response to the threat of terrorism from individuals connected with or inspired by Islamic State. Just one example of these new laws is an offence, punishable by 10 years’ imprisonment, for merely entering or remaining in an area of a foreign country declared by the foreign minister to be a “no-go zone”.

Australia came relatively late to the idea of supplementing coercive anti-terrorism laws with a national strategy for countering terrorist ideology and radicalisation. Indeed, these approaches still remain something of an afterthought in Australian counterterrorism. Because of this, there are as yet no formal requirements on Australian universities to prevent people from being drawn into terrorism.

This is one of the few admirable qualities of Australian counterterrorism. University lecturers are not trained counterterrorism officers, and it should not be part of their job description to help spot potential terrorists in their classrooms. In any case, the idea that it is possible to pick a terrorist out of a crowd based on a single profile – even by the most highly trained officers – has been proven by numerous studies to be false.

Any sensible university lecturer would rightly be concerned if one of their students began espousing radicalised views during classroom discussion. Such conduct would be discussed with supervisors and, if it continued, with the university administration and ultimately the police.

Undoubtedly there is a real risk of young individuals being inspired by IS and engaging in acts of terrorism on home soil. This was tragically demonstrated in Australia with the recent shooting of an accountant who worked for New South Wales police by a radicalised 15-year-old. Other teenagers as young as 12 remain the subjects of ongoing surveillance and investigation.

But turning this into a formal requirement of university teaching is likely only to generate the kind of suspicion and resentment that contributes to the ongoing threat of terrorism. It suggests a high level of fear and distrust, not only of Muslim communities but also of university lecturers, in terms of their ability to do their jobs while remaining aware of threats to security. We are not so distracted by philosophical questions that we cannot see when a student or event is likely to generate racial hatred or contribute to a risk of terrorism.

Higher education is in a worrying state when lecturers feel the need continually to emphasise that universities are places of learning and critical thought, not businesses and bureaucracies. It is of the highest concern when lecturers feel compelled to emphasise that they are facilitators of such learning, and not de facto officers of a national security service.

Keiran Hardy is lecturer in criminology and criminal justice at Griffith University, Australia.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: State of alert

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?