As students in England finish up their exams, and start to wonder how well they have done, the campuses in America have already become ghost towns. The academic caps and gowns have been put away for another year, and the new graduates are planning (or even starting) the next phase of their lives. Lives to be lived in Trump's America.

I wonder how they must feel? Many, I know, feel betrayed. Denied a life and jobs in a greener future.

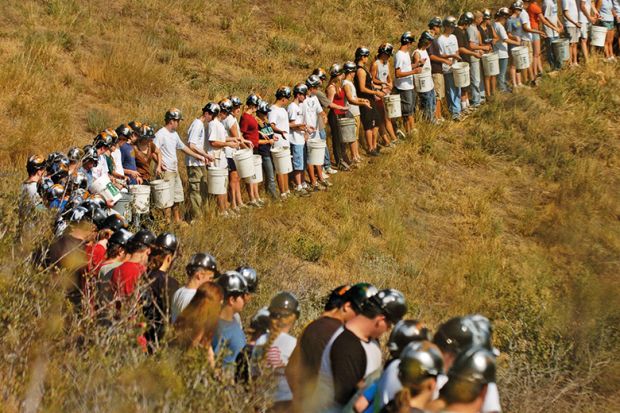

I actually went to a commencement (what Americans call a graduation ceremony) just a few weeks ago in Golden, Colorado. The sun was shining through the sweet clear air of the foothills of the Rocky Mountains as I watched the grandson of the man (a dear friend of mine) who invented the first portable respirator walk across the stage to accept his degree from the Colorado School of Mines.

The School was founded in 1874 in a state where the mining of all sorts has been crucial to the economy. This small but important university is a class act: the faculty of the CSM (known themselves as "Mines") has just won a Wall Street Journal award for utilising their research to the benefit of their students' education. And it undertakes a lot more than mining-related research and teaching.

Now you may think that a name like the Colorado School of Mines signifies a focus on coal, gas and oil. And you'd be right. In Golden, the mines are second only as a source of employment to Coors beer, and the "Ore diggers" can get pretty much anything out of the ground. But this award also recognised riches in science and engineering, from the geology of tar sands to the operation of fuel cells.

And this is where the CSM has a few surprises in store. Colorado has undertaken leading research on sustainable energy. In fact, Golden was the site of the foundation of the Solar Energy Research Institute, now the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, by President Carter, and was doing frontier work on solar energy in the 1970s.

I knew about these pioneering efforts because I had been asked to supervise the work of a graduate student at the University of Colorado, just down the road in Boulder, when I was on the physics faculty. The institute suffered a 90 per cent cut in its budget under the administration of President Reagan who did not accept the need for renewable sources of energy. This action meant research on solar was then developed in other parts of the world, but credit belongs to Golden for being present in the first chapter of this globally important work.

Today, CSM focuses more powerfully on multiple areas of sustainability. It has an impressive research effort in areas that affect the environment and energy production from nuclear reactors to wind power. Many graduates go on to work in the renewables industry, which now employs a lot more people than the coal industry.

Commencement celebrates the next generation of graduates ready to go out into the world and apply what they have learned. Sitting in the audience were three generations. I wondered what the speaker would have to say to the grandson of my former colleague and friend. Would he live up to this momentous occasion?

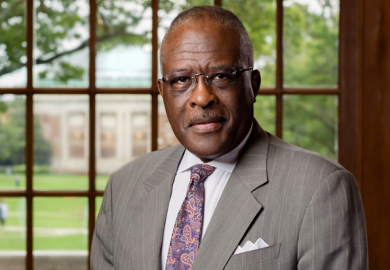

I need not have worried. The speaker had a distinguished academic career in applied physics and a global perspective. John M. Poate started with a PhD from the Australian National University in Canberra and then worked at the UKAEA at Harwell – one of the best-known places in the word for material science. His research had led him to work in or with many of the leading material laboratories across the world and he had served at CSM as senior vice-president for research.

His warm-up was self-deprecatory, noting that he followed in the tradition of "old farts" with a career of many mistakes behind them trying to give advice to a bunch of smart young people ready to take on the world. He got a laugh and the crowd was with him.

But then he got serious, encouraging his audience to see their own university in a global perspective. He talked of the other great schools of mines of the world: the École Supérieure des Mines in Paris, now Mines ParisTech (founded in 1783), and the Royal School of Mines (1851), part of Imperial College London.

And then he lit the blue touchpaper. He told the graduates about themselves.

With the proper authority of a scholar and citizen of the world, he told these young engineers and scientists that they were desperately needed in a world where science, and in particular climate change science, was under attack. They would need to work hard to prevent a disaster. They would even have to work to save the great Colorado river, which waters the “amber waves of grain” in their state.

As he explained the connection between a great tradition of scientific endeavour, the challenges of our world and the graduates’ future careers, a spontaneous burst of applause and cheers spread across the great hall.

And it was this that struck me. This may be Trump’s America – a president who has had a good deal to say about mining – but its able and fearless young citizens are determined that they will not turn their backs on what they believe are crucial frontiers for science.

Against the awe-inspiring backdrop of the Rocky Mountains, they listened to a man who has spent his life thinking and working on green technologies that might free us from the thrall of fossil fuels. They care that, if they really work hard, they might together save this home of ours. Not only beautiful Colorado, but the whole planet. Their cheers were jubilant and defiant.

It made me think of others who have given their lives to this endeavour. People such as two personal heroes of mine: Hannelore and Jeremy Grantham, who have dedicated their abilities, energy and money to understanding the environmental perils ahead and doing something about them. I thought of the young scholars and activists looking for answers and lobbying for change at my own university. It even made me appreciate those smart people in the oil and gas industry who do want strong environmental regulation to limit the damage, and who must surely also be part of any solution.

And I thought of the dangers we shall face if a new generation is prevented, by lack of funding, from helping us make these changes.

Make no mistake about it. These are profoundly dangerous times for our blue-green planet. The environmental cynics increasingly hold sway, and under their influence, President Trump has now pulled America out of the Paris Agreement on climate change. Scientists, engineers and environmental researchers who bring inconvenient evidence are increasingly underfunded or sidelined. Indeed, as I sat in the commencement, American Environmental Protection Agency's subcommittee members resigned en masse citing the "watering down of credible science".

So when the new graduates leave the School of Mines and similar institutions to face the world, will their ideals just fade with their memories? This is where the rest of us come in.

What happens next will depend on how much we value young people who will face in their lifetime the true challenges of the age. Who inherit an earth where avoiding conflict will depend on sustainable energy, clean water and food. Who will need new ways of thinking if they are to keep the amber waves of grain safe for their own children.

We have to protect their ability to discover and tell the truth, to face the facts about our problems so we stand a chance of finding a solution. And if America stops its children from being part of the solutions that are coming on apace, there will be many more jobs lost. Their lives and careers will be so much less than they could be. And the world will be cut off from the great powerhouse that is American science and technology.

We will need to listen to what they discover, to face up to the studies that tell us we need to change. The studies that remind us that we are not the sole inhabitants of our planet. That its “purple mountain majesty” and “shining seas” are part and parcel of a precious and vulnerable ecosystem that we ourselves inherited, and that we have a duty to pass on intact, so the generations to come can make their own way in our wonderful world.

Sir Keith Burnett is president and vice-chancellor of the University of Sheffield and president of the UK Science Council.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Protecting young scientists and the planet

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?