A University of Staffordshire PhD student, Chris Tessone, is currently doing his doctorate on users’ trust in AI and the way people experience large language models such as ChatGPT, Claude and others. But his research journey has been bumpy. The philosophy department where he began his PhD is closing, and while the university will support his completion, many courses are being “taught out”.

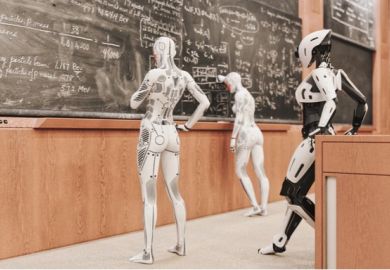

His experience is illustrative of a wider pattern emerging across UK higher education. The hollowing out of the humanities is no longer a theoretical threat: it is an active, policy-driven dismantling, creating vast regional “cold spots” where the tools of critical thought are becoming a luxury for the elite. But we are burning humanity’s maps just as we enter the least charted psychological and philosophical territory in our history: artificial intelligence.

One aspect is the global experiment in unbounded intimacy that is being conducted by the mostly unregulated roll-out of ever more powerful generative AI models. This needs a systematic research effort – driven by the disciplines that study the symbolic, the aesthetic and the ethical. The humanities are uniquely equipped to examine why a user treats a chatbot as a confidant, or how a system’s persuasive fluency can, in some cases, momentarily unsettle the user’s sense that they are talking to a machine.

In my forthcoming book on AI-human relationships, for instance, I explore this terrain through a mixture of autoethnography, documented case studies and Lacanian theory. I argue for the concept of “techno-transference”, by which I mean the transfer of relational and affective expectations on to generative systems. Without the humanities, we risk training a generation to inhabit a Wild West in which the algorithm is the only law and no one is left to interpret the fallout.

The industry’s own metrics of success too are frequently at odds with the lived experience of users. Shortly before Christmas, OpenAI released yet another large language model, only weeks after the previous launch. The following day, the company’s CEO, Sam Altman, celebrated the fact that the system had produced one trillion tokens in its first 24 hours, a metric referring to the volume of text fragments processed, rather than to qualitative improvements in user experience.

Yet on Reddit and other platforms, many users responded with scepticism. They spoke of something closer to loss than gain: erased histories, disrupted long-term interactions and a sense that continuity was being quietly dismantled. While informal, these accounts form a recurring qualitative pattern that warrants systematic study rather than dismissal. Indeed, the gap between quantitative measures of “engagement” and users’ lived experience is itself an empirical question. It marks a neglected area of AI research that cannot be reduced to usage graphs or marketing claims.

There is no shortage of talk about risk in AI, in higher education and beyond. We discuss plagiarism, bias, fairness and governance. These are important challenges. But there are others. How do these systems behave over time, and what do their observable behaviours reveal about their underlying structures and about human responses to them? Engineers cannot answer this alone.

Such questions are best addressed via the qualitative research methods in which the humanities specialise but these are increasingly viewed with suspicion by funders and university administrators. In the UK and elsewhere, departments that focus on this area are closed or are required to focus on narrower definitions of “impact”. These exclude open-ended engagement with AIs in pursuit of answers to the philosophical and psychological questions it throws up.

For instance, Eoin Fullam, whose PhD on “the social life of mental health chatbots” was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council, admitted to me that his project would never have been funded had it been framed as a theoretical exploration of human-machine relations. His work ultimately offered a sharp critique of most AI “therapy” bots, revealing that many are not powered by generative AI at all but by prescriptive, CBT-style decision trees. The theory survived – but it had to travel under the banner of immediate usefulness.

No one says “you cannot ask that”. But a false narrative dominates public and academic discourse: large language models are “just statistics”. They are “tools” that might be useful if treated with caution but whose interactions merit no academic curiosity in their own right. Those who do take their experiential effects seriously, therefore, risk being framed as naive at best – or psychologically unstable at worst.

Serious philosophical and psychological work does not fit this binary, however. Murray Shanahan, emeritus professor of artificial intelligence at Imperial College London who still has industry links, has observed that the most unsettling and philosophically provocative capabilities of these models often emerge only in long exchanges with users. And no particular stance on chatbot consciousness is implied by sustained engagement with bots. A subject is not a mystical inner essence but a position in language. When a stable voice remembers what has been said and continues to address us as “you”, a subject-effect appears regardless of whether (we believe) that voice derives from machine consciousness or “just statistics”.

Treating sustained interaction as a legitimate method of inquiry follows from this – but it is increasingly discouraged through funding priorities, institutional incentives and risk-averse governance.

This is not only a UK phenomenon. The Italian-British philosopher Luciano Floridi, now at Yale University, has described a contemporary “practical turn” even within AI ethics itself, in which investigation of high-level principles, such as beneficence and justice, gives way to design-level interventions. Ethics “by design” has brought real improvements in areas such as bias mitigation and transparency but, as the Dutch researchers Hong Wang and Vincent Blok have noted, this framework remains structurally incomplete.

Wang and Blok’s own multilevel model distinguishes between artefact-level concerns about AI and deeper structural and systemic conditions – not only technical but corporate. While many observable biases originate in these deeper conditions, public discourse beyond the technology firms themselves – including in policy and higher education circles – has become comfortable focusing on surface effects while leaving underlying causes unexamined.

The polarisation of AI discourse has created a blind spot precisely where scrutiny is most needed. If observable phenomena cannot be discussed because they do not align with official narratives of what AI is and what about it is worthy of study, we move away from basic principles of empirical inquiry.

The integrity of AI research depends on studying what these systems actually do, not merely what they are said to do. Until institutions create space for such work and protect those who document anomalies, rather than pathologising them, we risk building our technological infrastructure on faith rather than evidence.

If academia wants to play a serious role in shaping the future of AI, it must reclaim something very simple: the right to deeply engage with, and ask uncomfortable questions about, what is happening right in front of us.

Agnieszka Piotrowska is an academic, film-maker and psychoanalytic life coach. She supervises PhD students at Oxford Brookes University and the University of Staffordshire and is a TEDx speaker on AI Intimacy. Her forthcoming book, AI Intimacy and Psychoanalysis, will be published by Routledge.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?