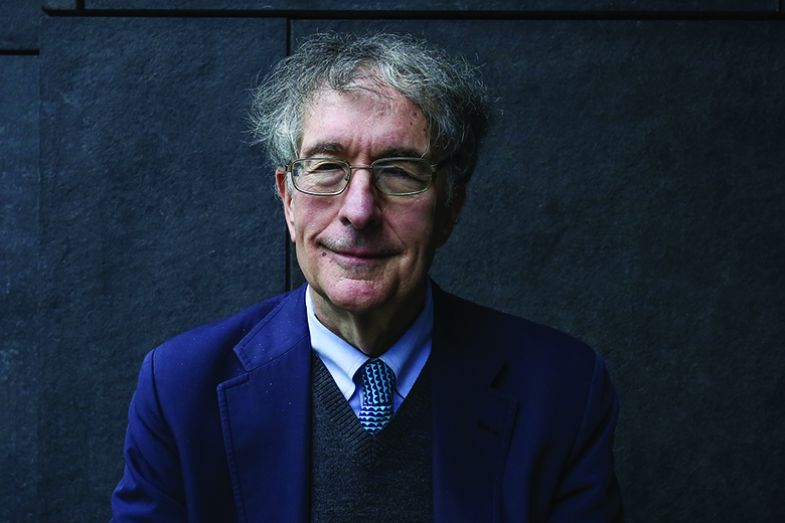

Howard Gardner has a history of challenging educational orthodoxies, not least with his much-debated theory of multiple intelligences.

Human intelligence, he argued, wasn’t just something to be measured on an IQ scale. People can be exceptionally smart on a variety of scales, including linguistic and mathematical, interpersonal and intrapersonal, spatial-visual and musical.

Some readers took the message, set out in his 1983 book Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences, as a foundational insight. Others saw it a bit too much like stating the obvious, without offering any actionable pathway for helping whoever was being shortchanged by the status quo.

Whether that was ever a fair criticism, the same high-stakes battle lines may now await The Real World of College: What Higher Education Is and What It Can Be – a 400-page report card on a decade-long dissection of American postsecondary life that Gardner has just published with his Harvard University colleague Wendy Fischman. In it, the two academics fret that our smartest young people are feeling shoehorned by their college experiences into a perspective on life that puts jobs and careers ahead of pretty much everything else.

THE Campus views: IPEDS and the trouble with student metrics in the US

“Just to have vocational education in the 21st century is suicidal,” Gardner – who is John H. and Elisabeth A. Hobbs research professor of cognition and education at Harvard – tells Times Higher Education. “Because a few years later you may be prepared for nothing, including citizenship.”

This is a fairly common refrain these days, but The Real World of College backs up its argument with a formidable amount of data. It is based on a six-year study, which began in 2013 and encompassed more than 2,000 detailed interviews, half of them with students and the rest with alumni, faculty, administrators and parents. The authors devote long stretches to making clear the intensity of their efforts. They regularly joined informational campus tours, eavesdropped in coffee shops and created a cross-team note-keeping structure that could mix stray student interview comments about sleepless nights with rigorous psychometric testing data. Then they spent two more years analysing it all.

Their analysis centres on a metric they created, termed HEDCAP: “higher education capital”. By this, they mean the ability of students to attack, analyse and reflect on challenges and communicate on issues of importance. They measured it by asking students 40 open-ended questions covering the academic and non-academic sides of campus life, as well as more general conceptions of higher education. Examples include how they spend free time, how they would change course structures, and what they think of their campus housing.

Drawn from cohorts of first-year students, graduating seniors and young alumni, the results showed that students usually grow on their HEDCAP measures during the years they spend in college, but not afterwards. Moreover, HEDCAP levels remain low overall. Not even a third of graduating seniors scored at the top level of the three-point HEDCAP scale. In one example that the authors noted with particular disgust, many students couldn’t name a book they would suggest to others at their institution. Those books that were recommended were typically high school-level texts, such as To Kill a Mockingbird or The Catcher in the Rye, or books typically read at even lower school grades.

In a nutshell, The Real World of College argues that US college students aren’t being encouraged to spend their four years exploring and thinking and improving the world, nearly as much as they’re being told to conform, perform and find their slot in the system.

“There are many students who come to college with their minds open and wanting to learn,” Fischman tells THE. “Unfortunately, they are getting mixed messages and mis-messages” about the need to concentrate on their employment prospects. “Higher education needs to get back to its mission of educating students and talking about intellectual growth, and embodying that from day one of when students come on to campus.”

Gardner was born in Pennsylvania during the Second World War, the son of Jewish refugees from Germany. He credits his childhood embrace of the piano – and his return to it in his seventies – with encouraging and then reinforcing his ideas about the variety of forms of human intellect.

A Methodist college preparatory school education took Gardner to Harvard, where he earned his bachelor’s degree in social relations. He expected in his graduate work to specialise in children and their artistic abilities, but he shifted towards neuropsychology – the study of relationships between the brain and behaviour – after attending a lecture on the topic by a pioneer in the field, Norman Geschwind.

In the mid-1990s, Gardner joined with colleagues at Stanford to create a group now known as the Good Project, which studies positive behaviours across society and develops initiatives to encourage more of them. One of the founder members of that project was Fischman, who dates her own interest in studying education to a 10th-grade project examining high-pressure testing in China. Shortly after completing her bachelor’s degree in history at Northwestern University, she moved into the project’s offices at the Graduate School of Education at Harvard and has worked there ever since, as a researcher and project manager.

It was within the Good Project that the pair decided to hone their focus on the values of the American workplace towards the world of higher education. That idea grew out a study by Fischman and colleagues indicating that adolescents and young adults recognised and admired noble professional behaviour, yet admitted with “little to no embarrassment or shame” that they didn’t abide by such ethical limits themselves. Examples cited by Gardner and Fischman include researchers lying about their methods in papers, journalists not checking sources, and students “taking a lead role in a theatre production that promoted racial stereotypes that they otherwise deplored”. For many young professionals, “‘good work’ was an aspiration for ‘later’ in life,” they conclude in The Real World of College.

That discovery led them to develop courses and other types of corrective interventions at Harvard and other nearby colleges. Then they sought to broaden their efforts to strengthen the non-vocational ideals of the postsecondary experience.

That notion is itself one riddled with politics, certainly including class and race. Defenders of the “Great Books” image of traditional higher education are caricatured in some quarters as promoting simple nostalgia for an age of young wealthy white men in ivy-covered libraries deifying the white ancients. Others take more seriously the use of classic texts in a liberal arts education that hones the ability of students to think and question: the ultimate preparation for the modern, ever-changing nature of 21st-century careers. But the question remains how low-income communities living pay cheque to pay cheque can realistically expect to attain that lofty experience for their children.

Gardner and Fischman launched a study of such scale and rigour out of the belief that the arguments on both sides of the value-of-college debate come with far too little data. “To borrow an old phrase, we wished that we were as sure of one thing as some of these authors were of the entire landscape,” they write. “The ratio of attitude to data was much too high." But while they insist that they appreciate the urgency of understanding the value of higher education – and the liberal arts in particular – in the contexts of wealth and race, they didn’t ask the students they interviewed to identify themselves by any demographic descriptors because, as Fischman puts it, "we didn’t want to put them on the spot” and “we didn’t want them to think that that was important to us, and that it would give them a lens through which they should respond to questions.” Furthermore, “if we found any differences [between different racial groups], we wouldn’t want to report them because that can get into dangerous territory.”

The authors were more interested in the HEDCAP differences between freshmen and seniors. They began their work at each campus by setting up a table advertising their interest as researchers in finding students who, for a $50 fee, would agree to be interviewed for an hour or so. The initial goal was 100 students per campus, with half of them freshmen and half seniors. But after securing about half the required number of interviewees on each campus, they looked at sample imbalances in certain areas – including gender, choices of majors, and participation in school sports and student government – and worked to even those out as they recruited the rest of the cohort. And although race and income were directly not among those variables, “we feel that our sample is representative of the colleges that we looked at,” Fischman says.

Having a diversity of institutions involved was important to the authors, with students polled from highly selective private institutions (Tufts University and Duke University), major public land-grants (Ohio State University) and urban colleges (New York’s Queens College and the Borough of Manhattan Community College). Olin College of Engineering was added as a “control” institution, on the grounds that the 330-student campus near Boston has clear vocation-oriented goals, alongside its embrace of liberal arts coursework and project-based content. Olin also has a financial heft – it was created by a foundation that left it enough of an endowment to initially finance all student tuition and that still manages to cover about half – far from typical.

When Fischman and Gardner’s data expose problems in higher education, they tend to attribute them to institutional misalignments. Among them is “mission sprawl”, in which students are left disoriented and somewhat despairing by too many extracurricular and co-curricular offerings. Another example is the frequent mismatch between the expectations that an institution professes and those that it conveys to its students and their families. Almost any college or university can do better by refining its mission as tightly as possible, the authors insist.

Steps in that direction, they believe, could include establishing more common courses that are taken by students across an institution. Colleges must also eliminate the “word cloud” of ambition reflected in official campus communications that blithely throw around such buzzwords as collaboration, leadership, citizenship and more.

“Even though they each have value,” Fischman says of these lofty lists of ideals, “when there are too many things, students pick and choose what they want. They interpret what’s most important, and the intellectual piece gets lost.”

The opportunity cost of studying is a central concern, Gardner tells THE. “It’s sort of the last chance to broaden your mind. The years before 25 are really the years when it’s easiest to think conceptually, to learn about new ways of understanding.” That means colleges cannot just pretend they are offering a unique educational experience if they are not. “Part of my answer would be truth in advertising. If you claim you’re expanding the mind, exposing people to lots of different fields and giving them the chance to explore, then you need to do that,” Gardner says.

The great shortcomings and inequities of the US grade-school system aren’t part of the study, but cannot be ignored, Gardner adds. In parts of Europe, the liberal arts are a central part of grade-school education. “But in the US, except for the elite secondary schools, you don’t get any kind of a broad education until you get to college or university.”

More traditional attempts to diagnose US higher education’s shortcomings certainly remain plentiful. One leading current example is the top-level commission convened last August by the Association for Undergraduate Education at Research Universities to revisit the 1998 Boyer Commission report on undergraduate education at research universities. Its key topics include interdisciplinary teaching and community building, and its final report is expected later this year.

A prominent champion of the Great Books approach, Roosevelt Montás, a senior lecturer in American Studies and English at Columbia University, has high hopes for the Gardner-Fischman effort. Montás just published his own argument for liberal education, Rescuing Socrates, and he welcomes The Real World of College’s data-intensive confirmation of the weakening of liberal arts component of higher education. It will, he believes, “make a difference” in changing minds among campus leaders.

“It gives me something that’s rigorous, something that’s methodical, and something that is exhaustive – to say, ‘This is not just my old man standing on a hill and screaming at the moon,’” he says.

Beyond seeing institutions post more precise mottoes to their websites, Fischman and Gardner call for each university’s newly narrowed mission statement to be clearly explained to students and families and to be implemented from admissions and acceptances all the way through to enrolment.

High-stakes grading should also be avoided, especially in early university years, the pair suggest. The pressure on students to think about their first jobs also needs to be reduced, they argue. The biggest surprise from their interviews, however, was the consistently high number of students who admitted or reflected mental health problems, or who just felt they did not belong. This leads to suggestions for everyone from college presidents and faculty to campus programme administrators and grade-school teachers centring on the importance of showing kindness to students, prioritising their mental health and emotional well-being.

However, Fischman and Gardner avoid giving any direct advice to groups with arguably the greatest ability to fix problems in higher education – the politicians and their voters. They nevertheless suggest that major power centres can and should be challenged more than is widely assumed. Presidents shouldn’t back friends to be trustees. Employers should think and look more broadly when filling positions. And – a holy grail for US higher education – athletics should be put “in its place”.

“Howard and I both believe that college is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for students to develop the mind, meet new people, learn about new disciplines, and become prepared for work in ethical ways,” Fischman says. “And if students don't give this thought then, as a society, we’re really going to be in trouble.”

POSTSCRIPT:

The Real World of College: What Higher Education Is and What It Can Be is published by The MIT Press on 29 March.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?