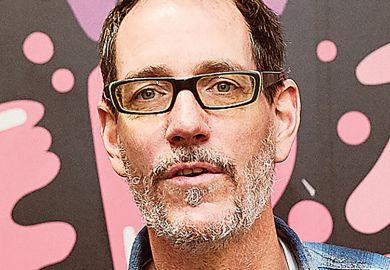

Gary Kayye is an assistant professor of media and journalism at the University of North Carolina. He is founder of The rAVe Agency, which provides marketing services to technology companies, and he has worked in technology branding and marketing for more than 25 years.

Where were you born?

I was born in Virginia but was given up for adoption.

How has this shaped you?

I don’t think it drove any changes in my life or drove the direction of my life. But it always made me curious about families and other people’s families – where they come from, and how it affects them.

What kind of undergraduate were you?

I was very involved in everything. I played intramural sports, helped candidates run for student government, and was very active in my fraternity. So, I soaked up the social experiences of college. Academically, I was very average. But the extracurricular is where I learned how to write and communicate. That’s been my most valuable professional contribution.

What has changed most in higher education in the past five to 10 years?

This new generation of students is unlike any other. Yes, there have always been generational changes. But other than maybe with the arrival of the printing press, [no other generation] has faced change this significant. Of course, we’ve had everything from video to television, to the internet and social media. But all those have been incremental changes. The exponential change came when all the recent things were made available to people [for] their entire lives. This generation of kids that entered college four years ago has only known a time where they were always connected and had access to every piece of information they needed all the time.

What effect has this had?

This generation of students naturally multitasks and naturally collaborates using these [new technology] tools. They can literally put on a headset and collaborate within two minutes. The way they learn is different; they use their cohorts more. That means that we need to look at the way we’re teaching; instead of teaching top-down, we need to start teaching more collaboratively. You can’t just deliver a class synchronously and expect every student to be there, attentive and always available. You need to make class available to them asynchronously, like putting it on Facebook for when students are sick or travelling. And teachers don’t always know everything – they need to bring in more outside experts.

Have you had a eureka moment?

[Realising that] meditation works.

How did you come to discover that?

It was recommended to me when I was probably in my mid- to late thirties as a way to change my state of mind. For the first two or three years, I kind of thought, “This is stupid, this is not going to work – meditation isn’t going to affect your state of mind.” But then, the more you learn about it and the more you think about it logically, you realise your mind and your body have a direct connection.

Have you seen that in the classroom?

I learned from a TED Talk, by mindfulness expert Andy Puddicombe, that only a short amount – as little as five minutes – is necessary. I tested it out in my classes for a few weeks, then a few months, and then an entire semester. Ever since then, in every class, I get the students to meditate. And I’ve heard from not just dozens but hundreds of students over the past eight years that they have incorporated it into their lives.

If you were a prospective university student facing today’s costs, would you go again or head straight into work?

It depends. The value of the university educational system is really in the diversity of exposure to what’s available professionally. Without it, you’d be limited by just what you already know. I grew up in a small town in North Carolina with maybe 5,000 people. Without college, my options for jobs would have been farming, or working at the local gas station or store. Certainly, if you have a family business, that business is going to teach you everything you need to know. But for exposure to the gamut of everything that is in the world, going to work without going to university would be very difficult. If you have a natural entrepreneurial bent, and you’re going to start your own business, I would suggest trying it at 18, 19 and 20 years old, because you have nothing to lose – you can always go back to college.

What brings you comfort?

This new generation of students – commonly referred to as Gen Z – is more conscious of the global impact they can have on the world than any other I have ever seen.

Aren’t young people generally more idealistic, only for that to change as they age?

Yes, when you’re in college, you’re more idealistic and think you can solve the world’s problems. But even in the 1960s when everything was falling apart, it wasn’t falling apart like it is today. And students today are being brought up in a more empathetic way; compared with students from 10 years ago, I think there’s a lot more inherent empathy in them.

What are the best and worst things about your job?

Best: teaching; worst: politics inside the university system.

What do you do for fun?

I race triathlons.

What’s your biggest regret?

Not starting to teach earlier. I didn’t start until I was in my mid-forties.

What is the biggest misconception about your field of study?

That you can’t make a lot of money doing it. You can, if you are creative.

paul.basken@timeshighereducation.com

Appointments

Paddy Nixon has been appointed vice-chancellor of the University of Canberra. Currently vice-chancellor of the University of Ulster, Professor Nixon previously spent five years in Australia at the University of Tasmania, serving as deputy vice-chancellor for research. Professor Nixon will take up the new role in June, succeeding Deep Saini, who is joining the University of Dalhousie as vice-chancellor. Professor Nixon said Canberra was “uniquely placed” to be a “national exemplar” of a “modern civic university” that served not only students but also the broader community.

Graham Carr has been named president and vice-chancellor of Montreal’s Concordia University for a five-year term. A Quebec native who has held several roles at Concordia since joining the department of history in 1983, including provost and vice-president, Professor Carr had been holding the role on an interim basis since last July. He succeeds Alan Shephard, who has joined Western University as president. Norman Hébert, chair of Concordia’s board, said Professor Carr “comes from Concordia and is already beloved within our community. He brings that knowledge and those existing ties as well as his constant drive, imagination and curiosity to the position.”

Chris Greer is joining the University of Essex as pro vice-chancellor for research (designate). He will work alongside existing pro vice-chancellor for research Christine Raines from this spring in preparation for the upcoming research excellence framework and the development of Essex’s new research strategy, before succeeding Professor Raines in August 2021. Professor Greer, a criminologist, is currently dean of arts and social sciences at City, University of London.

The University of Exeter has appointed three Mireille Gillings professorial fellows in health innovation: Sallie Lamb, Mireille Gillings professor of health innovation; Soojin Ryu, Mireille Gillings professor of neurobiology, and Chrissie Thirlwell, Mireille Gillings professor of cancer genomics.

Baroness Hale of Richmond, the outgoing president of the UK Supreme Court, has been appointed an honorary professor at the UCL Faculty of Laws.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?