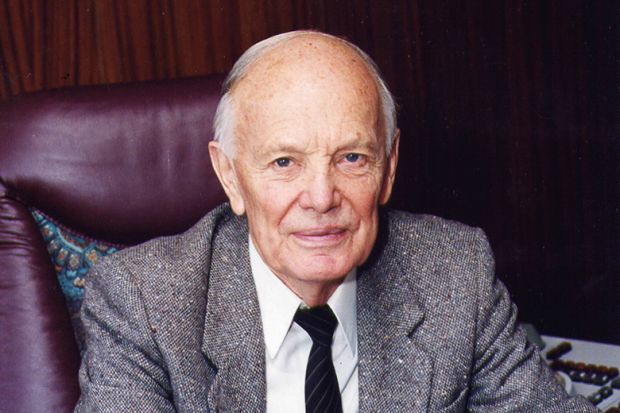

Boris Paton, president of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, will turn 100 on 27 November. He has been his country’s chief scientist since 1962. He is a renowned expert on electric welding and was awarded the Hero of Ukraine title in 1998.

Where and when were you born?

The National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine and I are exactly the same age. We both celebrate our birthdays on 27 November 1918. I was born in the professors’ residence building of Kyiv Polytechnic Institute, where my father, Evgeny Paton, was teaching.

How has this shaped who you are?

My father worked with such devotion [to engineering] that my brother Volodymyr and I could not but share his enthusiasm.

You grew up inside a university as a child. Did this influence your decision to become an academic?

The institute was my home and the first 11 years of my life were spent there. The corridors where I spent quite a bit of time remind me of my best, carefree years. Everything here is near and dear to my heart. So, it’s no wonder that later, in my adolescent years, when I was joining this institute, I felt as if I was coming back home.

What kind of undergraduate were you?

I spent endless hours solving problems, hundreds of those, one after another, just to practise. I did not want to disgrace myself in the eyes of the teachers, for whom I felt profound respect, nor to discredit my father, who was one of them. Besides, I studied the things that I loved with all my heart. And if you are engaged in your favourite work, that always makes the task easier, however difficult it might be.

What advice would you give to your younger self?

To work even harder and be even more persistent, as it is in the school and university years that the foundation of the whole human life is laid.

Your father Evgeny Paton worked in both Tsarist Russia and early Soviet-era Ukraine. How would you describe his primary contribution to science?

He was a genius scientist and inventor. My father did not lack the courage to radically change the sphere of his scientific interests at a fairly advanced age. He switched from bridge building to electric welding, as he saw a promising future for that area. He was excellent at both. Combining his previous experience in bridge engineering with welding technologies, he designed a number of unique bridges and supervised their construction, including the world’s first all-welded bridge over the Dnieper River, which connects its right and left banks in Kiev and bears his name. He was also the founder of the renowned scientific school [the E. O. Paton Electric Welding Institute]. His achievements would be sufficient for several human lives.

During the Second World War you designed electric circuits that helped to increase Soviet tank production. How important were such technological advances to the Allied victory?

Military superiority is always based on innovative technological solutions. The Second World War was no exception to this rule. It was waged within the framework of the so-called third technological wave, focused on mechanical engineering and electrical engineering. For this very reason, the T-34 tank, which relied on electric welding technologies, became famous. Scientific achievements and their deployment in the arms industry for war needs…played at least as important a role [in victory] as military talent and human heroism.

You were appointed president of Ukraine’s National Academy of Sciences in 1962, holding the post for more than 50 years. What was the most challenging era of your presidency?

It has never been easy. But there were truly hard times. Our academy endured a critical situation together with the whole country in 1986, during the Chernobyl disaster. We assigned all our resources to [minimising] the impact of the tragic accident. More than 2,000 employees of the academy’s 42 scientific institutions were engaged in this work.

Have you considered retiring?

As long as the academy needs me in the current difficult period, I will work. In nautical terms, it’s too early for me to jump ship.

What advice would you give academics on how to stay mentally active and physically fit?

You should put pressure on your brain and body. For many years I went in for sports – tennis, waterskiing, swimming. Now I still try to be in perpetual motion. This is both a habit and a need. I have also been able to deal with various problems because of an optimistic view of life.

Do you live by any motto or philosophy?

Work is the basis for everything. This maxim I inherited from my father, and he inherited it from his father. Parents should bring up their children not with mere words but, rather, with their own example, for children don’t listen to what one is saying but see what one is doing. In general, there was a rule in our family to work daily, work hard, and what was most important, to work effectively and obtain the result.

Do you have any regrets?

I am not a connoisseur of the arts. To my deep regret, I have never had time for that.

When should older generations stand aside for younger scientists?

The people of my generation and those somewhat younger still have a high degree of robustness. It would be a grave mistake not to use their experience for the welfare of the country if they can and want to share it. It is very important to properly combine the sagacity of the seniors and the energy of the young. Without that synergy we will step on the same rake as our ancestors did. “To raze everything and build a whole new world” – that principle does not hold true in science.

jack.grove@timeshighereducation.com

Appointments

Catherine Clarke has been named chair in the history of people, place and community at the Institute of Historical Research. She takes up her new role at the School of Advanced Study, University of London in February. She is currently professor of English at the University of Southampton and will head up a new research centre that will draw on the expertise of the IHR’s staff and its flagship projects within the Centre for Metropolitan History and Victoria County History. Professor Clarke, a specialist in medieval literature and culture, said that the new centre will be a “unique opportunity to shape innovative, transformative scholarship in the field, and to reach out beyond the academy to forge connections and drive transformation in communities”.

Jamie Maguire has been named the inaugural Kenneth and JoAnn G. Wellner professor at Tufts University. The neuroscience researcher, who was previously a tenured associate professor at the Massachusetts institution, joined Tufts in 2010, with her research focusing on disorders related to depression. Her work has led to the first potential treatment for postpartum depression, which is being reviewed by US medical authorities and is expected to be approved by the end of 2018. “I am delighted that the university has recognised Jamie’s accomplishments with this prestigious appointment,” said Harris Berman, dean of medicine, adding that Professor Maguire will “continue to make great contributions to our neuroscience research programme as Wellner professor”.

Anna Jensen is to become associate vice-president and university controller at Indiana University in January. She is currently the university’s chief accountant and managing director of financial management services.

Antoine Harfouche has been appointed professor of information systems and data analysis at EDHEC Business School. Professor Harfouche, formerly at Paris Nanterre University, is one of 11 professorial appointments recently announced by the school, which has campuses in Paris, Lille, Nice, London and Singapore.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?