Last week’s announcement by the South African government of a moratorium on tuition fee increases was a significant climbdown. The move, agreed in the midst of a huge protest outside the government buildings, will buy time for alternative options for university and student funding to be explored. But even solving this issue will still leave many others unresolved.

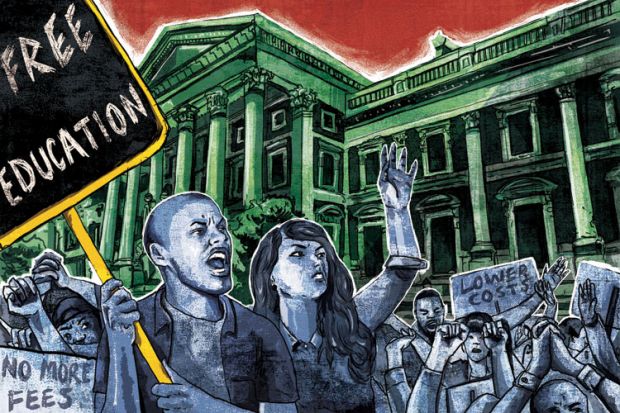

University campuses across South Africa have been simmering through much of this academic year. Over the past few weeks, discontent crystallised into a nationwide protest against proposed tuition fee increases, leading to campus closures and the disruption of exams.

While the cost of higher education is a real and pressing issue, South Africa’s universities are also a barometer of widespread discontent with the pace and direction of change 20 years after the end of apartheid. With 50 per cent of the country’s population under the age of 25 and both inequality and unemployment rising, wider fractures are beginning to show.

University fees in South Africa, which are unregulated, have increased steadily in recent years. The recent protests were triggered by some universities announcing rises of more than 10 per cent: close to twice the rate of inflation. Many students can barely afford food and housing at present fee levels; further fee increases will make it impossible for them to continue in higher education. They have little prospect of employment as an alternative to study.

Students who barely get by on campus often experience difficult conditions at home. There have been mounting protests against failures in the delivery of services such as water, sanitation and health in South Africa’s townships despite significant state investment over the past two decades. The prognosis for next year’s municipal elections has rattled the ruling African National Congress. A new and populist opposition to the ANC’s hegemony – the Economic Freedom Fighters – has joined up discontent over continuing inequalities with campus politics, and a broad coalition of activists is advocating rapid and fundamental change.

Protests began in February, at the start of the academic year, when the National Student Financial Aid Scheme (NSFAS) announced that it had insufficient funds to support all qualifying students. Student leaders at Tshwane University of Technology estimated that this shortfall, combined with the inability of students to pay off existing debt, would result in more than 20,000 students being excluded from further study.

In March, a protest that linked the inadequacies of basic facilities in the townships to the continuing legacy of colonialism brought together a broad coalition of black staff, students and low-paid service workers at the University of Cape Town. In August, a documentary revealing the continuing racism at Stellenbosch University went viral. The most recent protests, leading up to a national day of action on 21 October, were sparked by the University of the Witwatersrand’s announcement of a 10.5 per cent fee increase. Blade Nzimande, South Africa’s minister of higher education and training, has dismissed talk of a crisis; nevertheless, these are the most widespread student protests in South Africa in the lifetimes of many students.

The real costs to students of university study are often opaque and difficult to compare, with some institutions adding charges for services that their competitors include in their standard fee. Immediate issues may not be the overall cost of study so much as the scheduling of payments, with some universities requiring large upfront contributions. Others have put in place their own systems of economic redistribution, openly admitting to charging high fees to raise money that they can then allocate to low-income students as bursaries. But financial need is notoriously difficult to estimate, and there is little transparency in the processes followed.

Funding for the loans scheme has improved over the past decade, with a 20-fold increase since 1997. But the upper eligibility threshold is low and many working families, who have found it close to impossible to pay university fees at current levels, earn too much to qualify.

The NSFAS is also chronically inefficient. South African universities have very high levels of student non-completion, and growing unemployment makes loan recovery difficult. The NSFAS reports a 36 per cent decline in recoveries this year. Given this, and the pressure on the Treasury to fund basic education, housing, health and municipal services, it is unlikely that the state will pump more money into the student loan system.

In an initial attempt to head off further protests, vice-chancellors accepted Nzimande’s proposal for a voluntary cap on tuition fee increases next year of 6 per cent, the anticipated rate of general inflation. Students rejected the initiative, campaigning instead for no increase and for free education; however, the move has opened up the possibility of the statutory regulation of fee levels: a measure made all the more likely by President Jacob Zuma’s announcement of the fees moratorium over the heads of vice-chancellors. Given the very wide range of quality and demand for places across South Africa’s higher education system, determining fees for specific universities will not be easy.

Although state subsidies to universities have grown by 7.7 per cent over the past three years, vice-chancellors are looking to the minister for more. In response, the government has emphasised the autonomy of universities and their obligations to contain costs. In the meantime, few of the issues raised by students have been addressed.

The ANC’s general secretary, Gwede Mantashe, has accused students who have drawn the comparison to the Arab Spring of being “pseudo-revolutionaries”. Given the state repression that followed the uprising across a swathe of Arab states in 2011, vice-chancellors will take little comfort in this analogy, either. But the cost of education, rising inequality and widespread unemployment are bound up with disillusionment with both the state and the gatekeepers of knowledge and opportunity. Fees and payment requirements are a spark to a bone-dry forest of far greater complexity.

Martin Hall is the former vice-chancellor of the University of Salford. He is now based in South Africa.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Generation rage

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?