The University of Pennsylvania’s 2017 hiring of Joe Biden to a largely ceremonial faculty position is now paying off handsomely for the institution, while deepening the inequity in higher education that he often laments.

The Ivy League institution began paying the former US vice-president several hundred thousand dollars annually the year he left the White House to head its new Penn Biden Center for Diplomacy and Global Engagement.

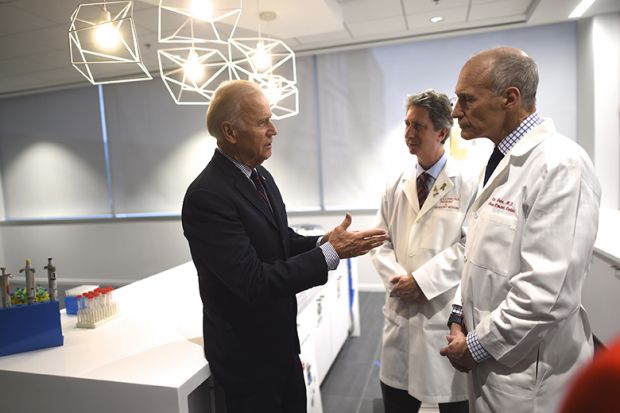

Although he held the title of presidential practice professor, Mr Biden did not teach classes. Instead, his work at Penn largely consisted of a handful or so of speeches and lectures over parts of three years.

The value to Penn included attracting world leaders to campus on numerous high-profile policy concerns, said a university spokesman. Mr Biden “helped to expand Penn’s global outreach, while sharing his wisdom and insights with thousands of Penn students through seminars, talks and classroom visits”, the spokesman said.

That positive publicity meant the roughly $900,000 (£670,000) that Penn has paid Mr Biden since 2017 looked like a good deal even if he had not won the US presidency this year, said Douglas Webber, an associate professor of economics at Temple University.

So now, with Mr Biden headed to the White House next month, said Dr Webber, a specialist in the economics of higher education, the pay-off looks spectacular.

“Being seen as having an association with a sitting president is almost always a good thing,” Dr Webber said.

The caveat, he and others acknowledged, largely reflects the outgoing US president, Donald Trump, a Penn alumnus whose contentious relationship with colleges and educators may leave him and members of his administration far less likely to find similar opportunities – if they even want them.

Already a petition is collecting signatures at Harvard University asking university leaders to be wary of hiring or even inviting to campus any Trump administration alumni. Some at Stanford University have been suggesting a similar approach.

Penn’s hiring of Mr Biden also has critics, albeit fairly limited, from faculty and students who questioned whether his salary might have been better spent in areas that included improving their diversity.

Nevertheless, said Robert Kelchen, an associate professor of higher education at Seton Hall University, the hiring by a large institution such as Penn of someone of Mr Biden’s stature was almost certainly a net benefit.

The more general risk with hiring political luminaries, Dr Kelchen said, likely involved public institutions that find jobs for former lawmakers in their states as a form of patronage.

Even the educational value argument in a case such as Mr Biden’s was legitimate, Dr Kelchen said. “If a person is hired as a professor of practice to teach students based on their experience, that can work out very well,” he said.

The incoming US president also assists the Biden Institute at the University of Delaware, his alma mater, but has drawn no salary there.

And yet, Mr Biden’s work at Penn could be seen as contributing to an overall widening of the inequities in higher education that the president-elect has pledged to fight, Dr Webber said.

That’s because Ivy League institutions that can afford to devote a faculty-size salary to someone such as Mr Biden disproportionately serve students from wealthy backgrounds who then gain top-level political connections, Dr Webber said. A similar level of expenditure at a state institution, he said, would be seen as clearly inappropriate.

Elite institutions also benefit from a well-established tradition of political appointees to federal office retreating to academia when their political party is out of power.

Examples just at the Penn Biden Center include Mr Biden’s nominee for secretary of state, Antony Blinken, a former Obama administration official who served as the centre’s managing director before he joined Mr Biden’s presidential campaign last year.

That practice can help students while giving government officials a break from the stresses of leadership that avoids the political baggage of many corporate jobs, Dr Webber said.

“It’s not less work” in academia, he said. “But there’s a lot less pressure than in government, where in many cases there’s life and death decisions, or at the very least things that people are going to be very angry at you for.”

The prospect of campus protests is just one reason why Trump administration officials were relatively unlikely to follow that pattern, said Elwood Carlson, a professor of sociology at Florida State University who studies politics and demographics.

The more fundamental explanation, Professor Carlson said, was that the Trump administration often hired “people who prefer blind obedience to making actual expert contributions to policy”.

“Most of them never would have been considered for reputable academic posts,” he said, “whether they joined this administration or not.”

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Professor Biden paid off for Penn, but did the rest of the US sector benefit?

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?