Sector sees dramatic fall in the number of fixed-term contract staff, improving morale and leading to better job security for researchers. Anthea Lipsett and Melanie Newman explain.

For Girish Ramchandani, a researcher at Sheffield Hallam University, his extended contract means he can devote more time to his work - and less to worrying about securing his future income.

Mr Ramchandani joined the Sport Industry Research Centre in 2002 and enjoys the peace of mind of knowing he has a secure job until 2010. Were it not for work permit complications, he would be one of many research staff enjoying the university's policy of improving job security.

"It definitely makes me feel more secure, and that makes it more fulfilling because I can devote all my time and energy to the research rather than wondering what will happen at the end of the year's contract," he said.

According to an analysis for The Times Higher by the University and College Union, Sheffield Hallam has among the lowest proportion of researchers on insecure contracts, with 48.7 per cent on fixed-term contracts in 2004-05, compared with up to 100 per cent of staff at other institutions.

Bert Jackson, Sheffield Hallam employee relations manager, said the university was committed to having as few staff as possible on fixed-term contracts, in recognition of benefits in the recruitment and retention of staff.

But he added that the nature of research funding meant there was sometimes no option other than to recruit some staff for the fixed term of a project.

The UCU analysis shows that Sheffield Hallam's attitude to improving job security is not unique: more and more research-only staff across the sector are being put on permanent contracts.

From a persistent high of about 94 per cent, the proportion of research-only staff on fixed-term contracts dropped to 93.2 per cent in 2002-03, and kept falling - down to 84.7 per cent in 2005-06 (or 31,601 out of 37,310 staff).

Janet Metcalfe, director of the UK Grad programme, said the analysis shows that universities are responding positively to the European Fixed Term Directive, which obliges institutions to make fixed-term staff permanent if they have been employed for more than four years.

"This is an important recognition of the substantial contribution that research staff make to our research base. But with 85 per cent still on fixed-term contracts, there's a long way to go," she said.

A spokesman for Universities UK said the changes were not simply a response to the law. "As part of the Research Careers Initiative there has been a concerted effort by the sector and the funding bodies to improve the conditions and terms of employment of postdoctoral researchers," he said.

Sally Hunt, UCU joint general secretary, predicted that figures for 2006-07, the first year of operation of the European directive, would show further improvement. But she added: "Casualisation in universities may be invisible to the public and students, but it is the unacceptable underbelly of higher education, and job security is still a major issue for thousands of academic and related staff.'

Ian Gibson, Labour MP for Norwich North and a former chair of the House of Commons Science and Technology Select Committee, said: "There was a worry that universities would slip around the new law, but they seem to be enacting it. The mood is changing, but many young people feel there isn't a future in the profession. The job for universities is to persuade them that there is."

Robert Gordon University has a good sales pitch. It has the least number of research staff on fixed-term contracts of all UK universities - 32.8 per cent in 2004-05.

David Briggs, its human resources director, said: "RGU has an exceptional record on the use of fixed-term contracts. We put it at the heart of our HR strategy as far back as 1998 when we recognised the 'no brainer' that expecting employees to commit to RGU when 40 per cent of our total workforce, not just research staff, were on fixed-term contracts was not a reasonable expectation."

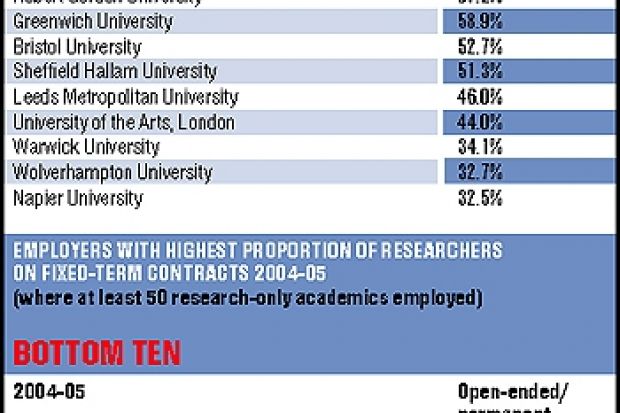

The universities of Teesside and London South Bank and the London School of Economics are bottom of the UCU table, with 100 per cent of research staff on fixed-term contracts in 2004-05.

Cliff Hardcastle, deputy vice-chancellor (research and enterprise) at Teesside, said the figures were "historical and deceptive".

"We have recently invested £1.5 million. This has culminated in an increase of 21 per cent in the number of permanent research appointments since 2004," he said. The LSE said it was in the process of moving staff on fixed-term contracts to open-ended contracts.

Lancaster University is ranked as the tenth-worst institution with 97.1 per cent of staff on fixed-term contracts in 2004-05. But it said the number dropped to 90 per cent of staff in 2005-06. "As a general principle, all posts should now be on an indefinite basis unless there is an objective justification why they need to be fixed term," a spokesperson said.

anthea.lipsett@thes.co.uk </a>

'Dismissal was a disgrace and an act of discrimination because of fixed-term status'

An industrial tribunal ruling that an Ulster University lecturer was discriminated against because he was on a fixed-term contract was this week hailed by union leaders as a "landmark decision".

Ulster was ordered to pay more than £36,000 in compensation to former social policy and sociology lecturer Andy Biggart after the tribunal in Northern Ireland found that redundancy procedures had not been followed when his contract ended two years ago.

Dr Biggart's lawyer said this week that the victory made clear that all fixed-term workers must be treated the same as permanent staff in any redundancy situation.

In a damning judgment, the tribunal described the reasons given by Ulster's human resources director, Ronnie Magee, for failing to stick to standard redundancy rules as "simply breathtaking in their arrogance and inadequacy".

Father-of-two Dr Biggart, who is now an education lecturer at Queen's University Belfast, was left unemployed for a year when his fixed-term contract at Ulster ended.

The university originally employed Dr Biggart on a five-year contract that was twice extended to enable him to finish his funded research. But the decision to axe his job was announced at short notice, with no effort made to redeploy him. His requests for an appeal were ignored.

The tribunal ruled that the university did not have any procedure for consulting with trade unions on the impending expiry of fixed-term contracts and was wrong in its assertion that to redeploy Dr Biggart would have been in breach of the Equality Commission's Code of Practice on Recruitment and Selection, which it claimed required it to advertise all permanent posts externally.

In its judgment, the tribunal said it was "astounded" to hear from Mr Magee that the university did not have a redundancy procedure because it had never made a permanent member of staff redundant and therefore did not need one.

Solicitors representing Dr Biggart and union leaders who backed him said the case clarified the employment rights of fixed-term workers.

John O'Neill, Dr Biggart's lawyer, said: "This ruling sends the message to universities and other employers that they must treat fixed-term workers equally with permanent staff in any redundancy situation.

"The failure of the university to discuss and consult with Dr Biggart over his options when his contract came to an end, and also to allow him a proper right of appeal against his dismissal was a disgrace and an act of discrimination against him because of his fixed-term status."

Sally Hunt, University and College Union joint general secretary, said: "This ruling, coupled with new fixed-term legislation, means universities who try to exploit their staff will not get away with it."

Dr Biggart said: "Although I feel the extent of the discrimination that I experienced was simply appalling, what disappointed me most was, in spite of my own attempts to appeal this decision internally, the university refused to engage with me and to see this through due process. This left me little choice but to take my case to tribunal.

"I am aware that the treatment I experienced was not an isolated case, and I hope, for the sake of my former colleagues, that the university will acknowledge the need to develop and apply fair and transparent policies and procedures."

A university spokesman said that Ulster was "considering the decision and recommendations of the tribunal".

Tony Tysome

'It made me feel more settled and able to concentrate on my research work rather than being distracted about where the next contract would come from'

*For Hua Lu, reader in computational science at Greenwich University, holding a permanent contract has brought psychological benefits.

Dr Lu joined Greenwich in the mid-1990s after a couple of fixed-term contracts at Sheffield University. He had three consecutive one-year and two-year contracts at Greenwich before being offered a permanent job in 2000 as part of a wider university move.

"It made me feel more secure and settled, and more able to concentrate on my research work rather than being distracted about where the next contract would come from," he said.

The feeling that the university invested in his research career also made him feel more attached to it as a result.

Greenwich is the third-best institution in the UK overall in terms of the number of research staff it has on fixed-term contracts: 41.1 per cent in 2004-05.

John Humphreys, Greenwich's pro vice-chancellor for research and enterprise, said: "The university has a record of winning research contracts, which means that we employ many staff - scientists, in particular - and, although funded through contracts, we are able to keep them on a permanent basis."

He said that the university was generally inclined to make permanent rather than fixed-term appointments unless there was a clear case to the contrary.

But it considers each individual case in detail.

"As a university, we have developed specialised areas of research, and we expect to continue to invest in the staff working in these fields.

"By and large, we feel it is better to have permanence in these groups, creating stability and building up a core of people who can commit their futures to the university. In turn, we can commit to their career development. That leads to success with better research performance and increased research income.

"We have a strong portfolio of business clients, arising from our commitment to applied and strategic research, and we find that established, permanent researchers provide a better base for growing this area of work and winning repeat business."

*The London School of Economics is among institutions that had100 per cent of research staff on fixed-term contracts, according to the University and College Union's latest figures, for 2004-05.

But the university said it was aware of the issue and was taking steps to address it.

"We are in the process of moving all staff who are on fixed-term contracts over to open-ended contracts.

"All research staff who have been on fixed-term contracts for more than four years and have had one contract extension are now on open-ended contracts," a spokesperson said.

The LSE is going to continue to phase out fixed-term contracts until all its researchers are on open-ended contracts it said.

*Leicester University also has a very high proportion - 98.3 per cent in 2004-05 - of its research-only staff on fixed-term contracts. Like the LSE, it is trying to make changes and transfer more of its researchers to open-ended contracts.

A spokesperson said: "In common with many other research-led universities, it is inevitable that a successful institution will have a significant proportion of staff on fixed-term contracts.

"The proportion of research staff employed on fixed-term contracts at Leicester had fallen to 94.4 per cent by the end of January. This is because, where appropriate, we have transferred staff to open-ended contracts.

"This process is ongoing and it is anticipated that the proportion of staff on fixed-term contracts will continue to fall over a period of time."

University officials have also been meeting with trade unions on campus to discuss the use and management of fixed-term contracts. They shortly plan to unveil for consultation a proposal for a new code of practice on fixed-term contracts.

Anthea Lipsett <P align=center> <P align=center>

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?