Source: Miles Cole

It was something of a running joke at Sussex that all the female mature students split up from their husbands before the end of their degree

In 1978, Judy Worham’s brother broke his neck in a motorcycle accident. As he struggled to “come to terms with being permanently paralysed”, she often visited him in hospital and began to reflect on what she would have felt in the same situation. Her biggest regret, she realised, was her “lack of achievement in formal education compared with my two brothers, both graduates from good universities”, so she decided to do something about it. After embarking on GCSEs and A levels, in 1984 and at the age of 38, she took up a place at University College London to study English.

This required a certain amount of juggling. Worham remembers an occasion when one of her daughters was sick with glandular fever and also very worried about a dehydrated guinea pig called Bracken, which had to be given water through a pipette every 10 minutes. With course notes spread over the dining room table, she recalls that she “ran up and down the stairs to attend alternately to pig and daughter” while thinking about “how to structure my essay, the argument I would put forward, and searching my memory for the evidence to back my points”. At one point, unfortunately, she accidentally dropped Bracken on the floor with an ominous thud. The essay, unsurprisingly, didn’t get finished until 4am.

Yet despite such challenges, Worham “loved the intellectual excitement and found that the necessity to complete the domestic fed in to my enthusiasm for the academic…It was a heady mix and I thrived on the intensity of my life.” Since no special arrangements were made to take account of many mature students’ family commitments, she “gained a huge level of satisfaction, sense of achievement and confidence in dealing with every crisis as it occurred”. After gaining her degree and a postgraduate certificate in education, she taught English in a further education college and went on to run the teacher training courses under the auspices of Canterbury Christ Church University. She has also written several books.

This is an archetypal uplifting story of university helping someone to turn her life around. When Rachel Bowlby, now Northcliffe professor of English at UCL, worked at the University of Sussex from 1984 to 1997, she witnessed a number of similar transformations among her mature students.

“The absolute standout”, she says, was a man who “started his degree in his late twenties in the mid-1980s. He was married and a father of three children, had been working in a garage and done some Open University modules. He was a natural from day one, got a first (when firsts were rare), did a (funded) PhD and ultimately got an academic job.”

The huge increase in participation rates over the past 30 years means that someone like this would now be much more likely to go to university in the first place. Studying as a mature student has become far more common, too, with the number of such entrants roughly doubling between the mid-1980s and the mid-1990s. At many universities, adult learners now make up a significant proportion of the student body (see ‘Universities with a high proportion of mature students’ table, below) and there is greater awareness of their needs, while flexible provision allows students to combine work and study. But how does it enrich teaching and learning when classes include older people among the callow school-leavers? And what challenges does this present?

Marc Cornock, senior lecturer in law at The Open University (who has also taught nursing and in other institutions), takes a very positive view of mixed-age groups. Mature students, he says, “have life experiences that they can bring to discussions and are usually able to articulate these to the younger students. They bring a different perspective to a common situation or a clinical discussion. Their views are often at a tangent to the younger students, who seem to learn a great deal from having the mature students with them. In return, the younger students usually ‘educate’ the mature students in the use of technology and more recently social media and are able to question the perceived wisdom as they have not experienced it.”

Recalling Sussex, Bowlby says, “it seemed a hugely positive thing that the presence of so many older students mixed up the ages. In those days…you were also exempted from the regular A-level requirements, so it could be a wonderful second chance for people who’d left school at 16 or messed up their sixth-form time.”

Such “second chances” often applied to more than just intellectual stimulation and job opportunities. It was something of a running joke at Sussex, as Bowlby tells it, that “all the female mature students split up from their husbands before the end of their degree…In other words, at least in the myth, they started to think and got fed up with their domestic lives. And from this you can gather that many of the mature students were women – and ‘housewives’ (remember ‘the housewife’?) – often doing a degree for something to do once the children were safely in secondary school or whatever. But I also remember feisty single mothers in their twenties and thirties, with young children…who were absolutely engaged intellectuals like the best of the 18+ students.”

Stuart Laing, now professor emeritus in cultural studies at the University of Brighton, where he served as deputy vice-chancellor until earlier this year, still remembers the very first undergraduate class he taught – at the University of Sussex in 1973. It included three out of five (male) mature students: “a former merchant seaman studying philosophy, a former lorry driver studying geography and a former travel agent studying history – all three older than I was. They all had great experience and quite broad knowledge. The trick was to know how to help them organise and discipline their knowledge and reflections into a coherent argument rather than merely let their ideas sprawl broadly. And also to avoid the other two class members (19-year-old women) being completely overawed and tongue-tied.”

More generally at the time, however, the majority of mature students at Sussex, particularly in the humanities and social sciences, were women, and Laing witnessed “some quite interesting contrasts between the 18-year-old school-leavers and, say, the mid-thirties mothers of two now wanting to catch up on something they had missed or which was not available to them 15 years earlier (when female students had been still in quite a minority).

“A typical seminar on the family might include bright and well-read 19- or 20-year-old psychology students who thought they knew all about children because they had read the right books and the mothers who thought they knew all about children because they had had one or two themselves. Both sets had to have their assumptions questioned and broadened with sensitive handling (especially in a seminar group where they had started arguing). When this worked well, it was very productive; when it did not, tensions could arise.”

Even more highly charged, adds Laing, were the classes where “class differences and age differences came together. In a much more elite system (even in the ‘newer’ universities) the cultural gap between an 18-year-old woman from a Surrey upper-middle-class family and a working-class man 20 years older – maybe with skills of argument honed at Ruskin College or in East End trade unionism – was huge. This might be compounded if the seminar topic, perhaps industrial history or D. H. Lawrence or social stratification, was one with a political edge.”

University can be traumatic, and as students get older it is more of an upheaval in their life and more of a challenge to their ways of thinking

Ronan Paterson, principal lecturer in performing arts at Teesside University, has also seen some of the assumptions that school-leavers can make about their elders challenged. On one comedy module he taught, some of the younger students thought that they might embarrass a mature female student with “some fairly risqué anecdotes about their sexual exploits”. Unfazed, however, “the older lady got up and delivered a monologue based on her own experiences over a 40-year period, which reduced them all to stunned silence. The audience’s laughter was at least as much at the faces of those who had tried to shock her as it was for her (very funny) stories.”

In Paterson’s experience, “mature students are generally the best students we have. They tend to be far more strongly motivated than a lot of 18-year-olds…[who often] think it’s simply an occupational hazard to miss a class because you’re hung-over.”

And Alison Lester-Owen, a senior lecturer in nursing at Glyndwr University who has taught “groups with student ages separated by decades, 18 to mid-fifties and older”, relishes the “richness” this brings to discussions. Since mature students can suffer from a lack of confidence “go[ing] right back to their school experience”, universities have to focus on “building back their confidence and providing both academic and emotional support when required…Timetables need to be flexible enough to recognise that many students are juggling family life, a part-time (or even full-time) job, and their education.”

Academics inevitably report a few painful experiences with mature students, too.

Nick Pearce, a teaching fellow in social sciences who works on Durham University’s foundation programme, notes that “going to university is a challenging and sometimes traumatic event for anybody. This is only magnified as students get older and there is more of an upheaval in their life and more of a challenge to their ways of thinking.”

The most challenging mature student recalled by Rosemary Ashton, emeritus Quain professor of English language and literature at UCL, is a non-native English speaker who “had overcome life problems (including divorce) and was determined to do well and get the most out of university. All of this was admirable, but she was difficult to shift when the tutorial hour came to an end. I would try to wind up the discussion, but she just carried it on. I would stand up, as if to usher her out, but she sat on. In the end, I had to ask a colleague to ring me up on the hour and require me to leave my room, which I managed to do, but still with her talking as I walked her out of the room!”

Yet there seems widespread agreement about the sheer – and often inspiring – levels of commitment that mature students are willing to put in.

When Bowlby taught at Sussex, “everyone was in effect getting paid for this privilege of being a student”, and “it was the mature students who sought to deserve that privilege and use it”.

Ashton appreciated the wide reading that many brought to their seminars, and also “the fact that they often speak up to fill a silence, not necessarily because they feel superior (in fact they often feel the opposite, as they are less close to having done their A levels) but rather because they have a stronger sense of social duty. They can feel for the poor teacher who is hoping for answers to her/his questions.”

Rosanna Cantavella, professor of medieval Catalan literature at the University of Valencia in Spain, sees this as part of more general generational trends. She usually has one or two mature students in each group and “always finds they are a joy to teach”. “The main curse of college lecturers at present is having to suffer the increasingly infantile behaviour of their students, especially freshers. I remember an era when it was unthinkable for us to ask our students to be quiet in class; now we’ve got to, from time to time. You’ll never have this problem with mature students,” she says.

Also very welcome to Cantavella is “the fact that mature students have, and show, respect for the subjects they’re learning, for the place where they’re studying, and (what a change!) for its lecturers. ‘Respect’ is a word many of today’s undergraduate students wouldn’t know from Adam.” In contrast, older students “recognise hard work when they see it and appreciate the service their lecturers give them”.

Although in reality her mature students are generally “more well read…most of them suffer from a certain inferiority complex that hinders their creativity, especially as freshers: they think their young classmates have a strong advantage over them in knowledge”. This means, explains Cantavella, that the lecturer’s first task is “to make them understand that, within the university world, they are at least level with the young”.

We can leave the last word to Worham. Among the school-leavers she studied with, a few were arrogant and others too “vulnerable…to speak up in seminar sessions”. Most irritating, however, were “those who seemed to me to be downright lazy…I was annoyed when we’d arrive at a seminar and I’d been up till two in the morning to finish the book in question to find some student come in through the door, sling her bag on the table and ask in a bored voice, ‘What are we supposed to have read?’…As a mature student I had such a hunger for it all that it seemed a criminal waste not to take advantage of the brilliant education we were being offered.”

Universities with a high proportion of mature students

| Institution | Proportion of first-year students aged 21 years or over |

|---|---|

| Source: Hesa data. Data is for full- and part-time first-year undergraduates in 2012-13. Apart from The Open University, the table excludes small and specialist institutions. * Institutions have subsequently merged to form the University of South Wales | |

| The Open University | 90% |

| Glyndwr University | 72% |

| London South Bank University | 68% |

| University of West London | 68% |

| Teesside University | 66% |

| Bucks New University | 65% |

| University of Wales, Newport* | 64% |

| Staffordshire University | 62% |

| University of Bolton | 62% |

| University of Glamorgan* | 60% |

‘The system’s modelled on 18-year-olds’

Fee hikes and the global recession are not the only factors that have contributed to the decline in the number of older learners

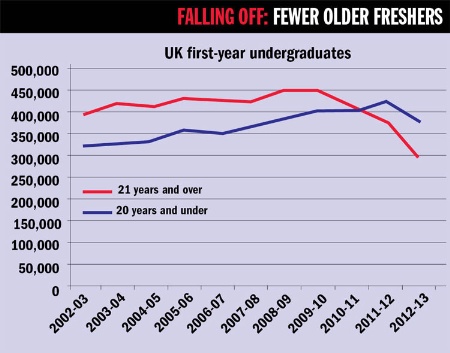

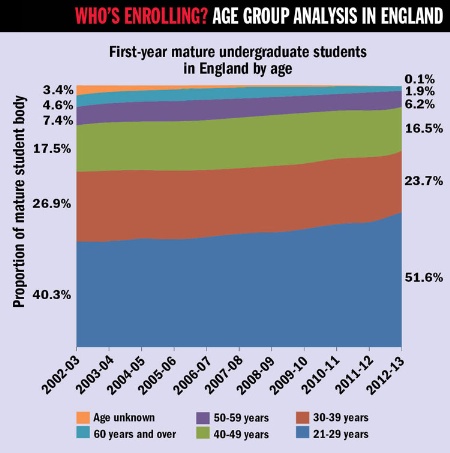

For many universities, including London South Bank University, Staffordshire University and Teesside University, teaching mature students is their bread and butter: among their first-year undergraduate student body, the majority of students are older learners. At The Open University, the UK’s open access distance learning university, mature students overwhelmingly dominate: 90 per cent of the institution’s 60,000-strong cohort of first-year undergraduates are aged 21 or over. But in recent years, across the UK as a whole, the number of mature students has been in decline (see graph, below). In 2008-09, more first-year undergraduates were mature (21 or over) than of school-leaver age (20 years and under), at some 450,000 and 380,000 respectively. However, by 2012-13, the latest year for which figures are available, the number of mature students had dropped by about 150,000 to about 290,000.

In England, the fall has been particularly steep: the number of mature first-year undergraduate students fell by 37 per cent between 2008-09 and 2012-13, according to data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency.

Mature students are more likely to enrol at post-92 universities, and Pam Tatlow, chief executive of the Million+ group of modern universities, says that older students have faced a “triple whammy” in recent years. Tuition fee hikes in 2006 and 2012 have coincided with a global recession and a real-terms fall in earnings. Employers, who sometimes support mature students with the costs of study, have also been “more reluctant” to contribute to the higher cost of tuition fees under the 2012 system, she adds.

“It is disappointing that the student support system continues to be modelled on 18-year-olds who study full time when one in three students now enters university for the first time when they are over 21,” Tatlow comments.

And she fears that other policy changes may do even more to reduce the flow of mature students entering higher education. For example, in 2013, public funding was scrapped for individuals aged 24 and over wanting to take Level 3 courses, equivalent to A levels, she says. Now students must pay for these qualifications up front or take out an Advanced Learning Loan, creating yet another “hurdle which those who are aiming to enter university later in life now have to cross”.

More recently, there have been some positive signs. Data from Ucas suggest that the number of full-time applicants aged 25 and over placed 15 days after A-level results day in England has almost bounced back to 2010 levels. That year, universities placed 34,800 students aged 25 and over. Although this fell to a low of 30,700 in 2012, it has now risen to 33,700 in 2014.

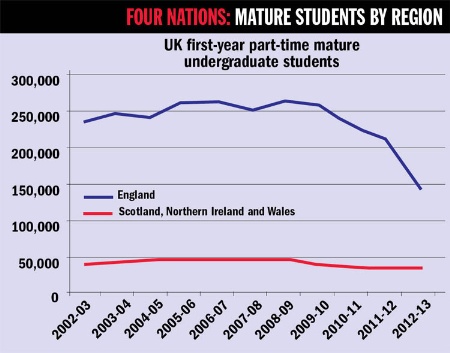

Les Ebdon, director of the Office for Fair Access, says that he is encouraged to see the “particularly strong recovery in acceptances this year”. Yet the Sutton Trust warns that the number of applications by mature students remains “substantially lower” than pre-2012 levels, particularly in England. And Ebdon says that he is “really concerned” about the “dramatic decline” in the number of part-time students. About 60 per cent of all mature students study part time, according to Hesa data, and a report from the Independent Commission on Fees published in August found that part-time mature student numbers are not bouncing back in the same way as their full-time counterparts. Analysis of Trends in Higher Education Applications, Admissions, and Enrolments says that 2012-13 enrolments for part-time mature students are down 43 per cent on 2009-10, a drop of 100,000 students. This is compared with a fall of 13 per cent for full timers aged 25 and over in the same period.

Claire Callender, professor of higher education policy at Birkbeck, University of London, believes that the funding system is contributing to this difference. Part timers, unlike those who study full time, are not eligible for loans and maintenance grants to help with living costs. “The only financial help that they can get is for their tuition fees,” she says.

“The assumption is that they are working and maybe their employer will help pay or contribute to their cost of study in some way,” she adds. But the recession has made employers less likely to fund study for staff, says Callender.

On top of this, many part-time students are not eligible for fee loans because they often have some kind of higher education qualification, and therefore fall foul of the so-called ELQ (equivalent or lower qualifications) rule. “Those people are having to pay up front, out of their pocket…and there is no guarantee that you are going to get a fabulous promotion having gained your degree,” Callender explains.

“If the decline in part-time students was only to do with the economy – with the increase in unemployment and the decline in household incomes – then you would expect the England figures to bounce back [as the economy improves], but they have not,” she says.

What has been the impact on universities that focus on widening participation for mature students? At the University of West London, which has campuses in Ealing, Brentford and Reading, a high proportion of the student body is aged 21 or over.

The university has seen a 7 per cent decline in first-year students aged 21 and over since 2010-11. In 2012-13, 68 per cent of first-year undergraduates fell into the mature age category, down from 75 per cent in 2010-11. But deputy vice-chancellor Kathryn Mitchell says that numbers have now reached a “steady state”.

The university’s portfolio is centred around professional qualifications, including degrees in nursing, midwifery, social work and hospitality, and Mitchell has a “hunch” that the number of mature students studying for professional qualifications has not fallen in the same way as for those taking more traditional academic degrees.

Maturity is an important entry criterion for nursing and midwifery degrees, for example, and nursing students are also eligible for NHS bursaries to pay fees. For its hospitality management degrees, the university has always looked for students who have some experience of the industry.

She says that the university works hard to attract mature students. Local employers often earmark staff to study at the institution. Fee waivers and peer mentoring schemes support a significant proportion of students, and the university runs open days that are specially designed for potential mature students.

Holly Else

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?