Whenever people talk about excellence in education, the Nordic countries are rarely far from their lips. High levels of funding and an egalitarian ethos are popularly believed to have created a utopian system that turns out academically exceptional students despite putting as much emphasis on extra-curricular activities as on book-learning.

But as cuts and shake-ups unfold across the region, some suggest that a harassed university leader would make a good protagonist for the next bleak Nordic noir television drama series.

Take Finland. Just months after being elected as prime minister last year, Juha Sipilä announced that basic funding to the country’s 15 universities and 26 polytechnics would be cut by approximately €500 million (£418 million) over his centre-right government’s four-year term, after a weakening of the Finnish economy. And €100 million of research funding would also be slashed: all this on top of cuts of €200 million imposed by the previous government.

The Academy of Finland, a government agency that funds scientific research via four research councils, says its funding for bottom-up research has dropped by 16 per cent over five years. When combined with a 43 per cent increase in the number of funding applications, this has led to a big drop in acceptance rates.

The Danish government is also imposing year-on-year cuts to its eight universities, beginning with DKr 180 million (£21 million) this year and adding up to DKr 700 million by 2019. The cuts are part of a wider effort to cull DKr 8.7 billion – or 2 per cent of the total – from overall education spending by 2019: the largest cuts to the budget in Denmark’s history. An additional DKr 1.4 billion and DKr 0.7 billion was cut from the DKr 22 billion research budget in 2016 and 2017 respectively.

Ulla Tørnæs, Denmark’s newly appointed minister for higher education and science, says that the centre-right coalition government “pursues efficiency in all parts of the public sector” and the cuts were made to ensure that “we get the best value for the taxpayers’ money”. The education cuts were also partly a result of the government providing more funding to other departments, such as healthcare and care for the elderly, she says.

In Iceland, between 2008 and 2012, state funding for higher education declined by 10 per cent as a result of its financial crisis (see 'Cooling-off period: Iceland’s slow recovery post-2008' box, below). And while university funding in Sweden has not yet faced cuts, it has levelled off; the government’s total expenditure on university education and research has remained flat since 2012.

The cuts in Finland have already had an impact on the country’s universities. According to a survey published by Finnish newspaper Keskisuomalainen, austerity measures introduced by the current and previous two governments have led to a drop of 5,200 university and polytechnic posts since 2012.

Jukka Kola, rector of the University of Helsinki, says that about half the budget cuts at his institution will be achieved through staff reduction, with the rest coming from increasing other sources of income, such as industry funding. In January, Helsinki said it would cut staff numbers by nearly 1,000 by the end of 2017 in order to reduce its budget by €106 million by 2020; 570 people have already been sacked, including 75 teaching and research staff. Prior to these cuts, the university had already shrunk staff numbers by 500 to reduce costs. The Finnish Union of University Researchers and Teachers held a candlelit vigil in front of the university’s main building in January to show support for those who will lose their jobs.

Aalto University, in Greater Helsinki, has also been forced to axe 350 positions – 17 per cent of its workforce – as it faces a drop of €66 million in government funding by the end of 2018.

But funding is not the only shadow that critics perceive to be threatening the eternal Nordic summer.

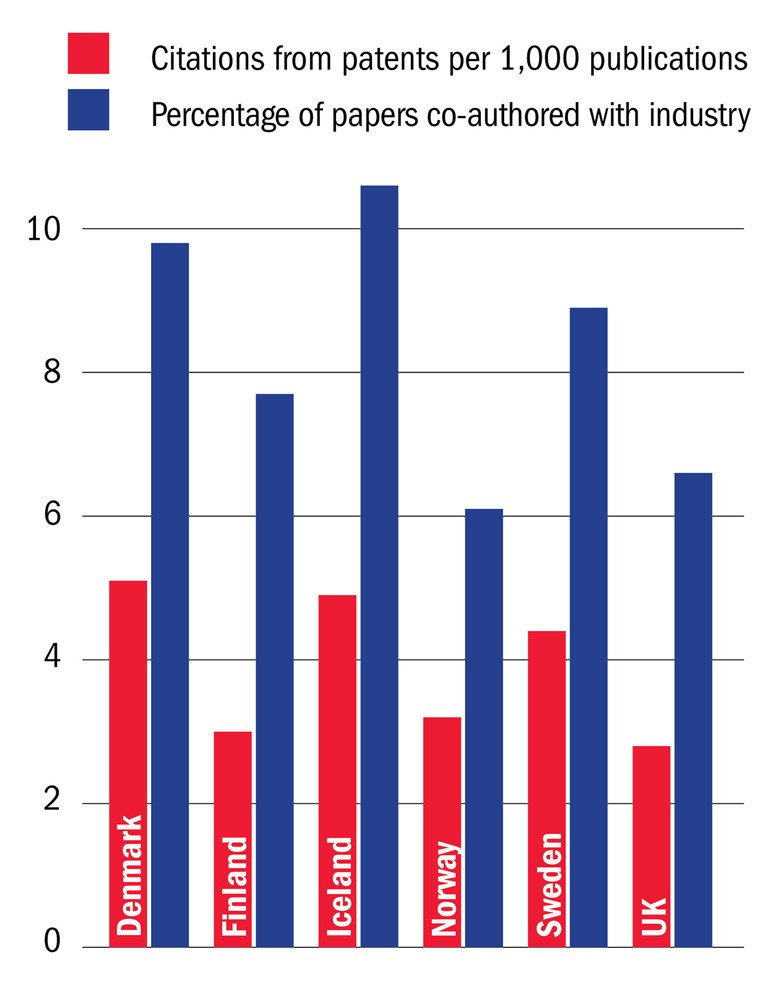

Outward focus: knowledge transfer

Note: Data relate to years 2011 to 2015.

Source: Elsevier’s SciVal tool.

One academic who relocated to Finland from the UK “fully expected a world-leader service that matched the outsider view of Finnish education in general”. But, he says, Finland is “not the academic super-being it is imagined to be” and his sense is that “my experiences are not isolated to just my university”.

“What I actually met was a lack of communication, no expertise in my area, no integration or funding, backward approaches to higher education – very apprentice-bound and blindly hierarchical – ill-informed subject and professional opinion [and] formulaic and oppressive approaches to supervision and teaching,” he says, adding that he has received no government financial support “other than some small amounts of statutory travel funding”.

There is also a “lack of academic quality standards”, he says, with “ill-defined assessment criteria, single marking and arbitrary mark inflation”. “Particularly worrying is the approach to publication quality,” he adds.

“PhDs are approved [on the basis of papers published in] predatory journal or self-publishing publishers [and] plagiarism is not uncommon and is poorly addressed. I am an academic editor and have seen four clear cases in the last five years.”

Heta Pyrhönen, professor of comparative literature, has worked at the University of Helsinki since undertaking her PhD at the institution in the early 1990s. She says that one of the main challenges has been dealing with “uncertainty” during the “constant” changes made by the institution’s management team. For example, she says her department has twice been merged, while degree programmes have also been redesigned; Kola, the rector, says that the institution will have just 32 bachelor’s programmes next year, down from more than 100 this year.

The restructuring “addresses our degrees on all levels – the bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral levels”, Pyrhönen says. “It addresses our teaching environments, our decision-making structures and our administrative structures.”

She says that most of the changes have been made “in a terrible rush” and there is no evaluation of their success before a new process is implemented. Morale has been particularly low following the firing of tenured professors, she adds. “That’s unprecedented. Of course, once it’s done, you’re left wondering when it could be done again.”

Gareth Rice, who spent six years as an academic at the University of Helsinki from 2008, before taking up “a more secure academic position” at an institution in the UK, says Finland “can no longer be held up as a world leader” when it comes to its higher education system.

Like others to whom Times Higher Education spoke, Rice stresses that his comments are based on his personal experience. But he cites the lack of “a culture of accountability” as one of his main gripes – an issue that, he says, predates the recent cuts and enables senior professors and research funding bodies to “circle the wagons and choose their favourites” when it comes to promotion or funding.

“In my experience of working in the social sciences, international academics are probably least likely to be favoured by Finnish funding bodies,” he says. “Those who are related to members on the decision-making boards will have the best chance of success. A number of researchers have told me that the system feels ‘stitched up’.”

He cites the Emil Aaltosen Foundation as an example of a Finnish organisation that generally offers academic research grants only to Finnish-speaking researchers. The foundation’s website states that in “exceptional circumstances” it is possible to grant an award to someone whose native language is not Finnish if the applicant is working at a Finnish-speaking university and is permanently living in Finland.

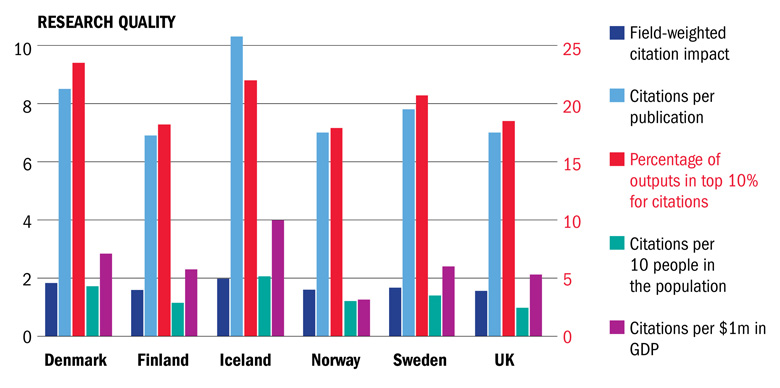

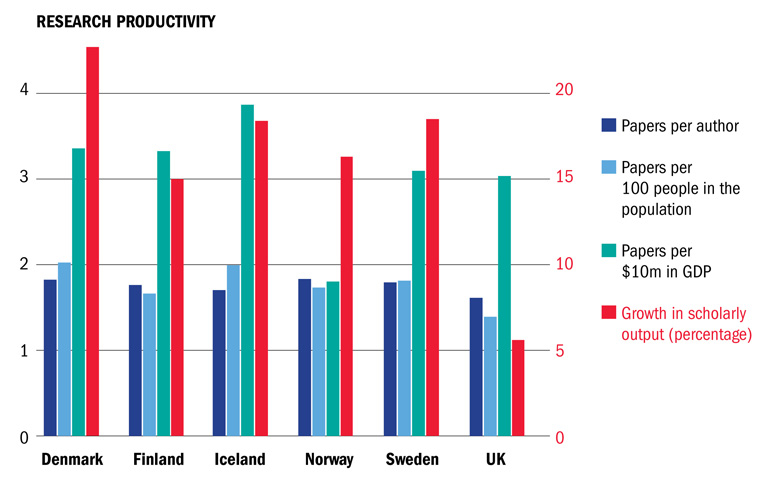

Paper weights: how does research shape up?

Note: Data relate to years 2011 to 2015. Field-weighted citation impact is a measure of citation impact relative to the global average in the relevant discipline.

Source: Elsevier’s SciVal tool.

However, a spokeswoman for the Academy of Finland, the country’s largest funder, says Rice’s claims do not match its own decision-making.

She says that in order to avoid conflicts of interest, 99 per cent of peer reviewer funding applications are recruited from outside Finland, and acceptance rates for international and Finnish researchers are “about the same”: so far this year, 15 per cent for Finnish researchers and 14 per cent for foreigners.

She adds that while the organisation has received a cut in non-earmarked government funding, its total budget increased from €320 million in 2014 to €420 million in 2016 thanks to new, competitive funding streams aimed at strengthening university research profiles, growing strategic research and boosting national research infrastructure.

Craig Primmer, professor of genetics at the University of Turku, is one foreign academic who has been successful at securing both academy funding and a professorship. The Australian, who has worked in Finland for 18 years, says that if there is any bias in research funding, it is that foreign academics are “potentially preferred” because of some research councils’ aims to boost internationalisation. He admits that it can be hard for foreign academics who do not speak Finnish to secure a permanent position because it is a legal requirement for all undergraduate teaching to be conducted in Finnish and, among academics, the working language still tends to be Finnish. However, while foreign academics may feel like they are “being discriminated against”, the situation in the country is “equally hard for Finnish people”, particularly young researchers.

Primmer says that one of the factors in his decision to stay in Finland for so long has been the country’s high levels of research funding. But he notes that both budgets and junior faculty positions have dropped over the past three years and, in his view, early career researchers “need to be considering whether this is a sensible career or not, because funding is so hard to come by and job security, which wasn’t great to start with, is getting even worse”.

Another major upheaval in the Finnish academy is the introduction of tuition fees for non-EU students from next year; the number of international students at Swedish universities fell by almost 80 per cent between 2010 and 2011 after tuition fees were introduced there. There was also initially a big decline in non-EU enrolments in Denmark after a similar move in 2006.

In Denmark, the University of Copenhagen has been forced to make similar cutbacks to Helsinki. Just five months after the country’s government announced its new budget, the university revealed it would shed more than 500 jobs – or 7 per cent of all staff. It has also reduced its PhD intake by 10 per cent and is removing some degree programmes, especially in languages.

Copenhagen’s rector, Ralf Hemmingsen, says the cuts “came out of the blue” after Denmark’s general election in 2015. Over the previous decade, increasing funding for universities and research had led to rising numbers of PhD candidates, a hike in the number of papers published in top journals and greater amounts of competitive research funding across Danish universities.

Hemmingsen says Copenhagen has not yet changed its “strategic goal of staying and possibly increasing our position as an international frontline research university”, but it would have to do so if the cuts “went on for five years. It’s important that the politicians revisit this theme within a year or two. Because if this cut is prolonged it will have a severe impact on research quality and, hence, research education,” he says.

Another concern for Danish universities is an upcoming change to funding allocations. Universities currently receive funding based on the number of students they graduate, but earlier this year the government said that a new system will base funding on the quality of students, graduate employability and “regionalisation”: a programme to support institutions outside the country’s major cities.

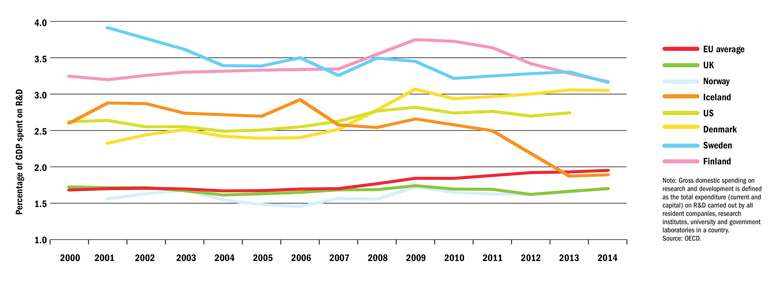

In the money: spending on research and development

Note: Gross domestic spending on research and development is defined as the total expenditure (current and capital) on R&D carried out by all resident companies, research institutes, university and government laboratories in a country.

Source: OECD.

Tørnæs says her main focus as higher education minister will be to provide “a better match between the supply of candidates and employer demand. Far too many young Danes experience the disappointment of finishing higher education only to realise that their dream education does not open the doors to their dream job.”

For Hemmingsen, this focus on employability is a concern. “Our difficult task is to explain to politicians that there has to be room for innovative, creative thinking,” he says. “It cannot all be [about creating] students that come out of the machine and immediately match a position that I can see just around the corner. You have to have some slack, enabling people to think freely and also sometimes to create candidates that create their own jobs that don’t fit into pre-set boxes.”

Per Michael Johansen, rector of Aalborg University, warns that the changes to the funding system “pose a tremendous threat” to Denmark’s universities.

“The total budget for the funding of university education in Denmark will not increase. That means that…some universities will be losers and some will be winners in this. That causes uncertainty,” he says.

He adds that it is vital that there is a connection between the cost of running a course and the funding received, but most of all, he says, he would like the changes to be “transparent” and “simple”, and for it to be “easy to foresee” the impact that internal university restructures will have on funding levels.

Tørnæs says that a panel of experts is currently exploring the metrics that will be used in the new funding system, while a reform of the regulatory framework of universities is also being explored. But, according to Johansen, Danish universities are worried because “this is something that is going on in closed bureaucratic circles…and we have no say in it. The government claims that when they have some metrics…they will introduce [them] to us before any decisions are made and we will have our say. But, of course, it [would be much easier to wield influence] if we had a seat at the table.”

Norway is the only Nordic country that is still increasing higher education funding each year. The Research Council of Norway’s budget increased to NKr 9.3 billion (£850 million) in 2016. This was a growth of 10 per cent since the previous year. The growth in budget per year has been between NKr 700 million and NKr 800 million over the past decade and the council’s input to 2017 budget negotiations calls for a NKr 1.2 billion increase.

Norway spends much less on research than other Nordic nations in relation to its total budget. According to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Norway spent 1.7 per cent of its GDP on research and development in 2014, compared with more than 3 per cent by Denmark, Sweden and Finland (see 'In the money: spending on research and development' graph, above).

However, Giosuè Baggio, associate professor in the department of language and literature at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, says it is “misleading” to look at these figures without taking into account the fact that Norway has a “huge GDP relative to its population”. In addition, about half of all research and development in the country is privately funded, he adds.

Publication outputs in the country have increased by about 89 per cent over the past 10 years, he says, but the quality and impact of research has not grown at the same rate – an issue he says the government is looking to address by developing funded research programmes for promising young researchers.

He would expect Norway’s centre-right coalition government to increase or at least maintain funding for universities over the coming years, particularly as the country is “trying to transition the economy to a post-oil model. There is lots of awareness among politicians that Norway cannot make a step forward if it cuts public funding for research.”

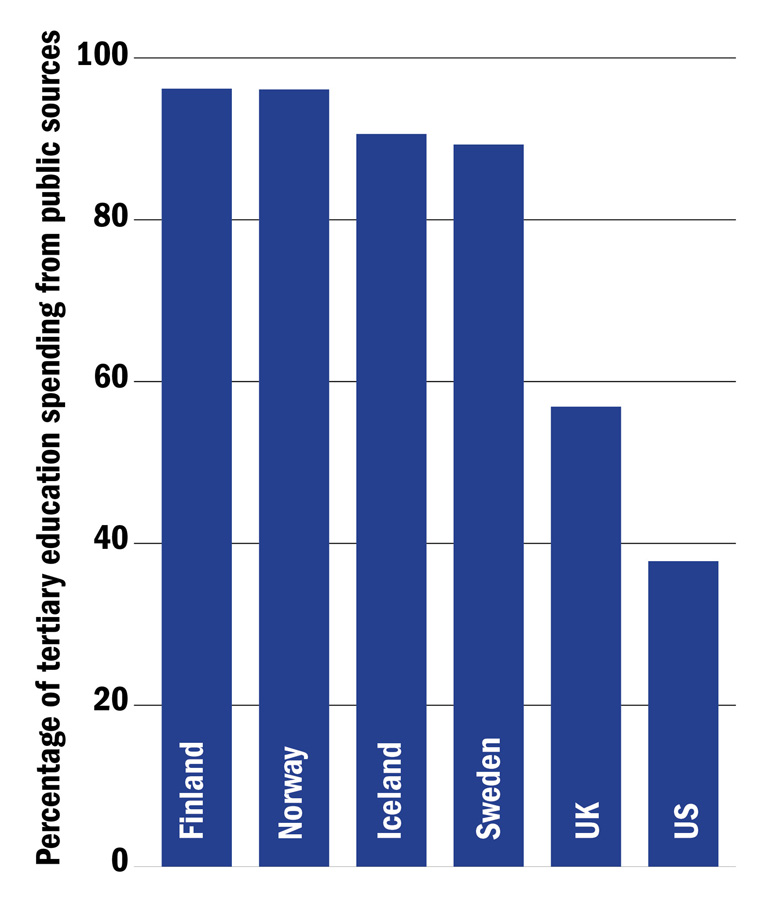

Public spending on universities

Note: No data are available for Denmark.

Source: OECD.

The government is also reviewing the structural funds it provides to universities, Baggio says, looking at whether a higher proportion of the money should be allocated on criteria other than institutional metrics, such as the number of students enrolled and PhDs awarded. Currently, just 2 per cent of these funds are allocated based on an institution’s publication output, which factors in both the number of publications and the quality of the journals, he says.

“This is very controversial and many have rightly criticised it because which journal is included in which tier is arbitrary,” he explains. “I think there’s a chance this will change and the reward of quality will get a little bit more sophisticated.”

Meanwhile, the Norwegian government is also focusing on improving the quality of teaching at universities, with a White Paper set to be published next year. When announcing the plan in January, Torbjørn Røe Isaksen, the country’s minister of education and research, flagged up the need to encourage students to study harder, make teaching more engaging and varied and better tailor higher education to employment prospects.

Ole Petter Ottersen, rector of the University of Oslo, says that the “most important aspect” of the proposals is the aim to “improve mentoring of students”. “There are the same discussions in other Nordic countries – how to cut back on the numbers of master’s programmes, for instance, to reduce fragmentation of the educational system,” he says.

Despite all the challenges for Nordic universities, figures from Elsevier’s SciVal bibliometric tool show that the region generally performs better than the UK does when it comes to the quality and productivity of research, and academic collaborations with industry (see 'Paper weights: how does research shape up?' graphs, above).

Sweden is no exception, but there is still a feeling within the country that it could do better. Its current research funding model is largely distributed pro rata – the competitive element accounts for just 20 per cent of the total and is based on just two indicators with equal weight: bibliometrics and external funding.

In 2014, the Swedish Research Council proposed the introduction of a peer-review-based research funding model to improve the country’s research performance. Sara Monaco, senior analyst at the Swedish Research Council, says the proposal, to which the Swedish government is expected to formally respond in October, involves the “same line of thinking” as the UK’s research excellence framework, except that there would be “separate panels for assessing scientific or artistic quality, and quality-enhancing factors and impact”.

Karin Dahlman-Wright, acting vice-chancellor at Stockholm’s Karolinska Institute, says the proposals have met with “mixed feelings. The advantages are that it establishes peer review within research, gives a more comprehensive assessment than [counting] publications, and, if done well, [will] drive quality,” she says.

“On the minus side, there is clearly some element of subjectivity in it, even if there are a lot of external reviewers. It’s also resource-intensive – regarding the efforts of the universities as well as of the external experts.”

Rice believes that Finland could benefit from exploring a similar funding model, incentivising academics to “publish high quality papers in international journals”.

“In Finnish academia there are staff reviews but these are nowhere near as rigorous or as demanding as the REF,” he says. “If Finland introduced its own REF, it would pile relentless pressure on to those academics with permanent contracts and weak publication records and [also] reduce the selection bias by opening up Finnish higher education to those with strong publication records who are looking to secure permanent employment contracts.”

However it is structured, Nordic rectors appear to be unanimous that continued university investment is crucial to the region’s prosperity. For Helsinki’s Kola, for instance, spending on education and research is the “only option” for his country.

“This is the way Finland will survive in the future,” he says. “For a small-population, export-reliant country, there are no other choices. We have only 5.5 million people. We don’t have any big natural resources, so it’s [about] education, knowledge, research [and] innovation.”

Cooling-off period: Iceland’s slow recovery post-2008

Institutions in Iceland are slowly recovering from deep cuts after the financial meltdown of 2008, explains Jon Atli Benediktsson, rector of the University of Iceland.

After the crisis, which wiped out many of the island nation’s banks, Icelandic universities suffered “a 20 per cent reduction in the budget from the government, but a 20 per cent increase in [student] enrolment”, Benediktsson says. “But still, after all these years, in terms of the contribution from the state per student, we are more than 10 per cent below what we had in 2008 before the crisis.”

The country’s research and development spending as a proportion of GDP dropped from 2.9 per cent in 2006 to 1.9 per cent in 2014, according to figures from the OECD.

Benediktsson adds that Iceland does not have a typical “Nordic university system”, characterised by high levels of public funding, a long research tradition, numerous support staff and high numbers of PhD grants.

However, data from Elsevier (see 'Paper weights: how does research shape up?' graphs, above) show that Iceland leads on both quality and productivity of research among the Nordic nations.

Benediktsson attributes this success to the research evaluation system adopted by the University of Iceland, which has approximately two-thirds of the entire student population of the country. Higher points are given to papers published in higher-ranked journals.

“The university has been transformed from a general university to a research university [over the] past 25-30 years,” he says.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Pressure points in Utopia

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?