The Tinkerbell effect

We all know the ideal. A university is not just another medium-sized corporation; it is a community of scholars, striving towards the common goals of learning and enlightenment. And we all know the many ways an actual university falls short of that ideal. Collegiality can evaporate in the heat of the job, with its daily irritations and power plays. The modern university, the American educator Clark Kerr once wrote, is just “a series of individual faculty entrepreneurs held together by a common grievance over parking”.

The managerialist ethos that pervades today’s universities doesn’t help. This ethos reduces human relationships to the incentivising logic and contractual obligations of a market. The problem isn’t the people – managers themselves can be well meaning and principled – but the system. Ultimately, managerialism does not believe in community, only in self-interested individuals completing tasks because they have been offered carrots or threatened with sticks. By dividing us up into cost centres, the managerialist university tries to isolate the ways in which the different parts contribute to the whole. Poorly performing areas, or those seen as a drain on resources, are put on the naughty step, or worse.

In this context, the rhetoric of the university as a community can feel like little more than message discipline, smoothing over dissent and critical thought. The language of corporate togetherness rings hollow at a time of casualisation, redundancies and unmanageable workloads.

Still, we keep believing. Collegiality responds to the Tinkerbell effect: the collective act of believing in it, sometimes in spite of the evidence, brings it into being. In the middle of this semester, we had a fire drill. When the alarm goes off, it opens up the building, decanting its dispersed human occupants on to the tarmac and lawn outside. The invisible life of the university is made visible. We stood coatless and shivering in the autumn air, huddled in little groups. I saw students I had only ever seen on Zoom, colleagues appointed since lockdown who I had never seen before, and others I had not seen for over a year, reassuringly unchanged. And I was reminded how much of a community is made by this mere fact of contiguity: passing each other in corridors, popping into offices, queueing up for the microwave.

These acts form part of what Katherine May calls “the ticking mechanics of the world, the incremental wealth of small gestures”, which “weaves the wider fabric that binds us”. As a shy and socially passive person, I rarely take the initiative in interactions, so I need these accidental encounters. I didn’t quite notice, while I was just trying to get through it, how much a year and a half of living online had messed with my head. I had to get well again before I knew how sick I was. After so many months of virtual working, these micro-expressions of the value of community feel like glugging down bottled hope.

Community is not some warm, bland, mushy thing. It is how complicated human beings learn to live alongside other complicated human beings – people who want desperately to be good but who are also self-absorbed, insecure, frustrated and afraid. Community is only ever a work in progress, rife with bugs and glitches. It is hard work.

That becomes particularly apparent at Christmas, as we try to find it in us to show peace and goodwill to people we find irritating and exhausting. The writer Loudon Wainwright, Jr called Christmas “the annual crisis of love”. A university is a permanent crisis of love. But crises are what we struggle through because it’s worth getting to the other side – and because a university is a community or it’s nothing.

Joe Moran is professor of English and cultural history at Liverpool John Moores University.

Time and tables

For many of us, this is the first Christmas in two years we will be able to spend time with our families. But while travel restrictions have largely disappeared and students have returned to campuses, we’re still not quite back to Christmases past. Instead of enjoying one last dip into the box of Quality Street circulating around the department before we lock up our offices, many of us will just be turning off our computers at home. Departmental meetings, academic seminars and even Christmas drinks have at many institutions remained online.

As a newly single parent juggling childcare with my academic career, this hybrid existence has mostly been a relief. It’s much easier for me to attend seminars when I can do it from home, a five-minute walk from my daughter’s school. And who among us has not sneakily fiddled with the PowerPoint for their next class or answered a few emails while attending an online meeting? Much about the pivot to online working has made my workday more efficient.

On the other hand, I don’t think any of us dreamed of getting into academia to be efficient. And I’ve been reflecting on the importance of unscheduled communication to making me both a better thinker and a better colleague. During one not untypical recent week, I sat down with colleagues to eat lunch and talk about both impact case studies and planned edited collections. I also ran into another colleague in the hall, and we brainstormed possible ideas for collaborative teaching.

This, of course, was fostered by us all being in the same place. We could have had those conversations by email or Microsoft Teams, but that would have taken planning, which may not have happened. Besides, the results of scheduled meetings are rarely filled with the serendipitous joy of chance encounters. As software engineer Shawn Hamman argues from his experience as a team leader, “being remote creates a constant overhead of having to actively manage and engineer communication to compensate, mostly imperfectly, for the lost ambient signals, informal chit-chat and various serendipitous encounters” that are a part of daily life when people are co-located. One of my colleagues confesses that he got more impatient with colleagues during the pandemic, and he is sure part of the reason is that opportunities to just chat had evaporated, reducing communication to all work and no play.

Is the solution to return to the face-to-face activities we took for granted in a pre-Covid world? I don’t think it’s as simple as that. In a survey by the UK’s University and College Union, four out of five academics said they were struggling with their workloads. The average working week in higher education is now above 50 hours, with 29 per cent of academics averaging more than 55 hours. With industrial action upon us again, the bald truth is that for many academics building community is at the bottom of their priority list. As another colleague told me recently, “excessive workloads in universities fracture a sense of community because colleagues do not have the time or energy to engage” with activities and events outside of their immediate to-do list.

Community building is work; it doesn’t happen by magic. Even that seemingly serendipitous sharing of a lunchbreak to talk about work was only possible because three of us happened to be able to spare the time to sit down together instead of gobbling a sandwich while answering emails. Time increasingly feels like a luxury in academia, with 78 per cent of academics surveyed by the UCU last December reporting that their workloads have increased during the pandemic.

Having space and time to think and talk should not be luxuries in the modern university: they are critical if we want to forge relationships between colleagues, build research connections and develop our teaching praxis. I’m hoping that some day soon we all will be together – but it won’t be if the fates allow: it will be if our workloads better reflect our human needs as researchers and teachers. That, rather than office parties, would guarantee merry Christmases yet to come.

Rachel Moss is a lecturer in history at the University of Northampton.

The global village

Desolate campuses, digital exhaustion and remote students with declining mental health were the experience of university academics the world over in pandemic-spoiled 2021. But with the festive season upon us, let us take a moment to celebrate at least one momentous achievement of the academic community this year, and to welcome the real promise of the next.

Unquestionably, academics should be proud of the pivotal role they played in addressing the Covid-19 crisis. This consisted of research to swiftly develop vaccines, tests and treatments, and also of partnering with pharmaceutical companies to translate research findings on a global scale. It also involved advising governments and health authorities about national and local pandemic policy and planning. Without universities, the progress made in many countries would have been slower and much less sure-footed.

And there is much for academics to be hopeful about for the coming year. In almost every survey, more than 90 per cent of students in Australia are reported to be hungry to return to face-to-face campus life. The boasts of the global edtech companies – that the pandemic heralded the triumph of fully online degrees and signalled that universities would eventually exist only in the cloud – seem increasingly fanciful. Our students endured online-only delivery while they had no choice, but few liked it. They want back the vibrancy of the academic community.

Moreover, 2022 presents causes that should re-energise and inspire traditional collegial spirit. Our students are passionately exercised by the climate crisis, sustainability and protecting biodiversity, issues with which almost every university department can deeply engage through research, teaching and public discourse. Students are also concerned by the increasing fragility of democracy itself, and they would be excited to see the academic community defend its values, including free speech and academic autonomy. And many are motivated by the world’s continuing social inequity, the correction of which remains dependent on equitable access to education, especially of the kind a university can provide.

Meanwhile, academia as a whole faces a unifying foe: the blizzard of misinformation from social media, which has eroded respect for the expert voice, objective evidence and indeed the empirical scientific method itself. On this issue alone, the global academic community should feel called to a crusade, a mortal battle seeking to oppose the destruction of evidence-based science, one of the glories of modern civilisation.

But some will argue that the community of scholars is doomed, as endemic underfunding of universities seems only to worsen, accelerated by the privations of the pandemic. Certainly, no one is predicting an end to university underfunding; but, again, the scholarly community can offer hope – through global networks. In research, international networks have been in place for more than a decade: the discovery of the Higgs boson in 2012 and the first observation of gravitational waves in 2016 are just two of the major scientific advances of recent years that depended on international, multi-institution research partnerships assembling resources across borders, way beyond the capacity of any single university.

Meanwhile, in teaching, universities like Arizona State are now growing global teaching faculty, with the expertise of the university’s salaried academics enriched by offshore adjunct appointees, who can teach in other fields via digital delivery, producing a course menu for students way beyond that any university could have afforded alone.

Truly, the coming years offer universities an array of exciting possibilities. As they plan their future, it is time for academics to draw sustenance from colleagues, students and global partners in their unique community, the character of which is no less promising now than it was when universities were first conceived, so many centuries ago.

Warren Bebbington is a professorial fellow of the L.H. Martin Institute, University of Melbourne. He was previously vice-chancellor of the University of Adelaide.

Closing the book

For Christmas this year, my university is closing the campus bookstore.

Astoundingly, given the significance of the event and the impending arrival of the festive season, this is not general knowledge among academic staff. Most of my colleagues, still stuck under an avalanche of marking, have not yet learned that by the time they emerge, Omnia Books will only exist in the archive.

Indeed, I only found out by accident, when, last month, I purchased a tin of body glitter and a permanent marker (which is another story).

“This marker is half price,” the cashier said. “We’re shutting down.” The woman, Dot, according to her name tag, was sixty-something, with oversized glasses and silver-white hair pulled back in a tight, no-nonsense bun.

Before I could respond, she corrected herself. “We’re being shut down by management.” She scanned the marker. “No money, apparently.” Dot adjusted her glasses. “Did you know the university just purchased a A$1 million flight simulator?”

In hindsight, news of the bookstore’s closure should not have surprised me. The University Co-op Bookshop chain went into voluntary administration in 2019, and though it was eventually bought by Booktopia, Australia’s leading online book retailer, during last February’s peak in Covid infections, the sale did not include the Co-op’s physical stores.

The Co-op initially operated from the garage of the two University of Sydney students who founded it in 1958, but failed ultimately to uphold its promise of affordable access to textbooks. In the mid-2000s, when membership maxed in the millions and the company managed over 50 stores, the Co-op’s chief marketing officer smugly reflected on the brand’s durability: “Our heritage has been, and will always be, universities.”

Of course, he could not have known that two decades later a global pandemic would empoison an already deadly concoction of high-price commodities, low in-store sales, and soaring shipping costs and delays. In the US, according to the American Booksellers Association, one independent bookstore has closed each week since the pandemic began.

The university bookstore is one of the last remaining cultural hubs that genuinely supports the core business of the academy: knowledge production and transmission. It is not just a shared space for students and academics, but also the general public.

Bookshops, as community centres, are gathering places that have long been allied with cafes and libraries – informal and inclusive spaces that embody the community’s heart and vitality. As public venues that foster creative interaction and civic debate, bookstores welcome locals and strangers alike. And books themselves are magical objects that can forge bonds, bridge divides, and mediate the sometimes acrimonious relations between town and gown.

Indeed, in regional areas, the university bookstore is often just as important to the township as the institution itself. As the author Neil Gaiman writes in American Gods, “A town isn’t a town without a bookstore.”

Certainly, in Toowoomba, a regional city in west Queensland, Omnia Books is the only retailer of affordable art supplies and specialty stock, and one of the few suppliers of dissecting kits, lab coats and sphygmomanometers (blood pressure monitors, since you ask). STEM students and art students, often separated by an epistemological gulf, will be united by grief when the bookshop closes its doors.

Even less forgivable is the neglect of hard-working staff, who are losing their jobs at Christmas. Dot has worked at the bookshop for 15 years; she has called in sick twice: once when her dog died, and once when she fell down the stairs and broke her wrist. “It was just a hairline fracture,” she says. “Nothing major.”

Of course, there will be consequences for the plutocracy too. Those who find the coffee on campus too weak or too strong will be down in the dumps, since the bookstore, as Dot reminds me, is the only shop on-site that sells sugar and milk.

“That’s all management really care about,” she says. “You know, that’s what someone said to me: ‘Where will I buy my milk?’”

Kate Cantrell is a lecturer in writing, editing and publishing at the University of Southern Queensland.

Capital gains

Universities are integral parts of capitalist societies. Identifying the workers, bosses, consumers and commodities is harder and less clear-cut than it is in an Amazon warehouse, but community is just as difficult to establish and sustain in universities as it is anywhere else in an atomised world of self-advancement.

In a pure capitalist system, money pays for a commodity. So what commodity is the university producing? There are lots of possible answers: degrees, research, jobs, brand association. Does that mean that students are the customers? On one level, absolutely: they pay their money and expect an education. At the same time, many also work for the university to pay for their tuition.

The administrators are certainly bosses, though most of those outside the very top jobs tend not to think of themselves like that. And we can be sure that the workers include the staff – maintenance, cleaning, catering – who literally keep the place running. The teachers, though, are a more complicated category. Sometimes they are workers, sometimes they are bosses.

Tenured or tenure-track professors are often legally considered bosses (in private institutions, it is very difficult for them to unionise, for instance). They almost never think of themselves that way: they work to produce research. But, particularly at PhD-granting institutions, they are gatekeepers of their domains. They expect to reproduce versions of themselves in their students, not understanding that the conditions of the academic labour market are far more precarious and competitive than when they were students decades ago.

Then there are the adjuncts, teaching assistants, lab instructors, visiting artists, postdoctoral fellows, and so on. These ranks are definitely not management, but they might not think of themselves as workers. The pipe dream of landing a secure position sustains a good many of them, who view themselves as “pre-tenure-track” (or pre-management) rather than as adjunct labour. Sometimes union efforts have produced job security for some adjuncts, in the form of renewable contracts or the equivalent, but many are resigned to the eternal purgatory of casualisation.

These vastly different levels of job security and prestige make the teachers an incredibly fractured class – and the high degree of specialisation of their academic training exacerbates this silo effect. Tunnel vision among those climbing the pyramid results, at best, in a lack of solidarity, and, at worst, a startling level of hypocrisy: self-styled “scholar-activists” who betray their co-workers down the hall.

For some, getting out of a system in which you are tokenised and commodified is the healthiest option. But simply leaving does little to change the system. And loud invocations to “burn it down” almost invariably end up being reformist in their execution. (Unless you literally do try to burn it down, but be warned that under capitalism, the institution will survive anything short of a thorough job.)

Let’s be clear: the university is an inherently counter-revolutionary environment. It may house dangerous ideas, and people who talk a big game, but when it comes down to it, few will leave the safety of their jobs or forgo their bigger-than-yours paycheques for the sake of others. Why do you think tenured and tenure-track faculty almost never go on strike in the US? As an institution, the university’s ultimate function is to simply continue existing, with or without you.

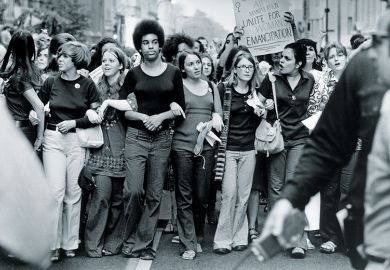

But the more we ask questions about who the workers and bosses are, the more the waters get muddied. Students and teachers can exploit staff. Teachers and staff can defend or betray their own. Recognition of this opens up a space for community and solidarity to develop: take the recent strikes or threats of strikes by lecturers and graduate students at the universities of California and Michigan. And those dangerous ideas and people – plus the ready-made enemies of administrators, professors and managers – hold the potential to bring genuinely revolutionary actors into being.

So what are the battles that we should pick? Which are the hills to die on? How can we imagine community, complicity and solidarity in the university through better understanding the function of labour, money and power in its everyday function? We must find our own answers through love and struggle, together.

Tian An Wong is an assistant professor of mathematics at the University of Michigan, Dearborn. He was an adjunct faculty member for nine years.

Nobler aspirations

One big, happy university family around the tree, enjoying our sepia-tinted memories of cosy Christmases past, anticipating a brand new year when we can change the world (again), enriching the lives of all of our students by working in perfect harmony together…

Bah! Humbug!

It’s been us versus them for decades now – senior management pitted against those of us at the chalkface. With the latest round of strikes, the conflict at the heart of UK universities is once again exposed to the elements: sustained attacks on pensions, increasingly unmanageable workloads, an ever-expanding culture of casualisation. And right at the core of these bitter disputes is the absence of what should be the lifeblood of any university, indeed of any organisation: trust.

The baseless pseudostatistics of metrics and rankings have been prime movers in eroding the trust between colleagues – including, in particular, between senior management and the rank and file – that is essential for collegiality and cooperation. We’re now pitted against each other, to the extent that, in many universities, individual academics have their very own data dashboard so they can monitor just how their stats compare with the average within their school or faculty. We work much harder and much longer than previous generations. We are praised from above for our dedication during the unprecedented times of the pandemic, while in the same breath we are criticised for not hitting our targets for student satisfaction, admissions or research income/productivity (by otherwise numerate senior academics who cannot be unaware of the statistical illiteracy that underpins so much of the miasma of their metrics).

Instead of trusting us to do our job to the best of our ability, senior management introduces ever more arcane measures to monitor and rank performance, paranoid that if they take their eyes off us for just a moment, we will slacken off, and the university will go tumbling down those all-important national and international rankings. (Times Higher Education is not entirely blameless in promoting this mindset, it has got to be said.) It’s insulting.

Just as insulting is the routine, elaborate pantomime of “consultation” with staff, where all involved know that it’s an exercise in futility: feedback is sought, feedback is given, feedback is dutifully ignored – except, of course, when it helpfully agrees with the strategic decision that’s already been made.

Yet there’s an upside to this divide. That “us v them” mindset can dramatically strengthen collegiality at the coalface. I very much hesitate to make mention of Dunkirk spirit – we’ve had more than enough tiresome jingoism in recent history as it is – but there is often a prevailing mood of togetherness in the face of adversity, of battening down the hatches to protect what is ours against the all-consuming centre. And this collegiality, importantly, includes the administrative and technical staff within – or connected to – a school, department, institute or unit. I can think of many occasions in recent memory where academics have fought hard for administrators to remain in-house: to continue to be part of our team. We push back against the creeping corporatisation of our workplace. Together.

“I have seen your nobler aspirations fall off, one by one, until the master passion, Gain, engrosses you. Have I not?” The Ghost of Christmas Past haunts us all. Let’s hope that in 2022 we can start to regain some of those nobler aspirations, look beyond the metrics and the world rankings, and rebuild trust right across the university.

Merry Christmas, one and all.

Philip Moriarty is professor of physics at the University of Nottingham.

Home truths

In 2017, professor of political science Robert Kelly went viral as “BBC Dad”, when his two children burst into the scene behind him during an expert interview for the corporation’s news channel. The clip, which has had more than 45 million views on YouTube, became a spectacle – clueless kids dancing in, Kelly visibly embarrassed, his panicked wife shuffling the “troublemakers” out of the room seconds later – in part because it let viewers behind the scenes, giving us access to the very real, very human company the professor keeps.

We did not know then that such moments would become normalised only two years later, as the pandemic sent academics, teachers, learners, administrators and others into Zoom rooms for university courses and meetings. Virtual engagement could have led us to view each other as disembodied minds behind faces on a screen, extending a dynamic that frequently occurs when we pick up a book and read someone’s words as though they are not connected to a real person in communities of other people. My own observation, though, was that the opposite occurred on many fronts. The making visible of our previously hidden home environment helped us to view each other as more fully rounded human beings. Cats and kids joined the academic community, as professors shared tongue-in-cheek posts about their colleague needing a litter box change, or napping all the time, or refusing to nap.

There is a clear ethical reason to embrace the expanded personal universes we now have access to. We should acknowledge embodiment as a human condition and think more richly about how we contextualise all the ideas, arguments, datasets and textual interpretations that comprise the lofty purviews of higher education.

Ideas never exist by themselves. There are no lone intellectual superheroes. The degree to which our communities support or shape our work varies by institution and by academic field, but we have never worked in isolation from each other. What is plain to us now is that many of us never even worked in isolation from our communities when we were confined to our Zoom rooms – whether that thought helps us or haunts us or both.

Of course, there is also a cost worth naming to all this. Our access to others’ homes is risky for some, exacerbating or at least laying bare economic disparities. Not everyone is benefited by having their material and family lives on display. “Room rating” is a tough business.

But the virtual shift opens up an opportunity for university communities to take seriously how many of their constituents’ participation is conditioned by domestic space and life, and by families – however defined. And this consciousness of the whole human being beyond the academic reputations and personas can only make those communities stronger.

Jill Hicks-Keeton is associate professor of religious studies at the University of Oklahoma.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?