“It’s all too easy to remember the target but to forget what it represents,” John Denham, the universities minister of the day, told vice-chancellors in 2008.

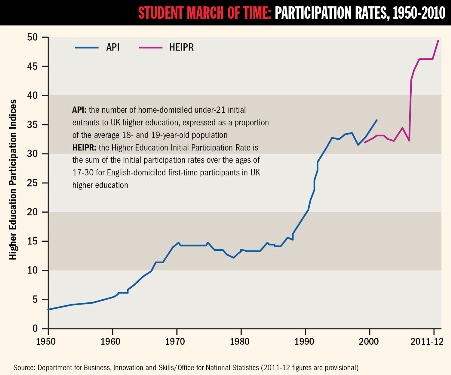

Fourteen years after Tony Blair first set out the aim, Labour’s goal for 50 per cent of young Britons to enter higher education has been all but reached.

According to the latest data, participation rates among people aged 17 to 30 rose from 46 per cent in 2010-11 to 49 per cent in 2011-12, and might even have exceeded 50 per cent had the figures included those attending private institutions.

So what does this mean? In 1950, just 3.4 per cent of young people went to university, so today’s participation rate vividly illustrates how higher education has moved from the margins to centre stage in British public life. What is more, this is a shift that has taken place within the lifetime of many scholars working today.

With this in mind, Times Higher Education invited five academics of different generations, and one recent graduate, to describe their experience of university and what entering higher education meant to them, their family and their peers.

The snapshots hint at just how much has changed, from the class concerns discussed by philosopher Baroness Warnock as she writes about the University of Oxford in the 1940s, to the focus on employability among the Class of 2013.

Mary Warnock

Mary Warnock is a philosopher, a cross-bench peer and a former mistress of Girton College, Cambridge. She was one of seven children. Her mother came from a well-off family; her father – a housemaster and teacher at Winchester College, the 600-year-old public school – died in 1923 after contracting diphtheria. Warnock began her studies at the University of Oxford in 1942, during the Second World War, in the days when compulsory schooling stopped at 14 and only a fraction of the population went to university (an even smaller proportion of them women). While Oxford began to award degrees to women in 1920, Cambridge did not follow suit until 1947. Warnock graduated in 1948, the year in which Agnes Headlam-Morley became the first woman elected to a full professorship at Oxford.

I was born in 1924. Many of my friends went to university and we in no way thought of ourselves as pioneers for doing so; but most of our contemporaries at the girls’ schools I attended did not. Many school leavers went almost straight into the forces and attended university after the war.

I was the youngest in the family, a posthumous child. My much older brother went to Oxford from Winchester as a matter of course, but the two sisters either side of him didn’t: they were “presented at court” (as debutantes) when they left school. However, my sister (who is two years older) and I took it for granted that we would “go up”, if we should be lucky enough to get in – and specifically to Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford, which was thought by my mother to be relatively upper class.

I dreaded the thought of not getting in. I was determined to follow my brother and his future wife, whom I loved, and read Greats (Classics). But neither of the Classics teachers at school knew much Greek and their teaching did not help me to avoid the most elementary howlers, both in Greek and Latin, nor did they have much confidence in me. But the school came to pieces in 1940 and I went on to have a blissful year at a very different school, where the head was a classicist who actually believed in me.

However, I went up to Lady Margaret Hall with few illusions. My older sister had gone up in 1939 and wrote to me with tales of horror. She made some friends, but none so glamorous as her school friends; the food was awful; and she was surrounded by enemies who thought Lady Margaret Hall was wonderful and who couldn’t imagine anything more jolly and delightful. When I arrived she had left; but things were as she had described them. We were meant to love “the Hall”; we were meant to suck up to Emily, who dished out our food from behind a hatch and gave double helpings to the girls she liked; we were meant to laugh at “the princ” (the principal) and to enjoy putting on the freshers’ play, which I, to my horror, as senior scholar had to write and produce, a task for which I was totally unfit.

I had two friends, one a marvellously funny and clever person, Nandy Pym, whose father had been chaplain of Balliol, and who remained a close friend until her death, and who, like me, was reading Honour Mods (the first part of the course). We supported each other through all the horrors, academic and domestic.

My other friend was Elisabeth de Gaulle, the General’s daughter, who was reading history and whom I got to know by the chance of sitting next to her at breakfast on our first morning and liking her sadness and wit. Through Elisabeth, surprisingly, I got to know her tutorial partner Catherine, a girl from Wallington Grammar School, on whom Elisabeth relied in many practical ways, and of whom she became very fond. She was indeed a dear kind girl. But Elisabeth (with whom I once had a terrible row, because she thought there ought to be first-class carriages on the Underground for people like her, arguing that it would leave so much more room for ordinary people) regarded Catherine, partly, as an anthropologist might a strange tribe. She could not hear enough about the etiquette by which Catherine was conducting her courtship with her RAF boyfriend, Stan. I felt slight pangs of guilt about this, but for Elisabeth it was a source of nothing but fascination.

Lady Margaret Hall was a weird and unreal place in those years. When I came back again in 1946 after a short spell teaching, although the food was worse and the cold more intense, in other respects it was unrecognisably better. It, and we, had grown up.

Christopher Bigsby

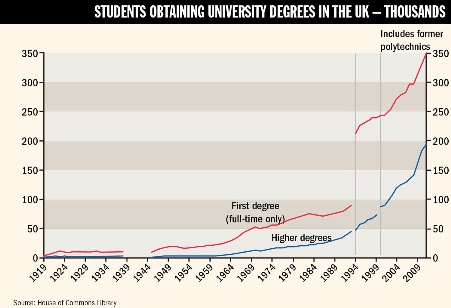

Christopher Bigsby is professor of American studies and director of the Arthur Miller Centre at the University of East Anglia, and a novelist. He went to university in 1959. In 1960, fewer than 22,500 full-time students obtained first degrees in the UK (by 2011, the figure had grown to 350,800). But the numbers were rising steadily as a wave of institutions – known as “plate glass universities” – opened during the period and “marked new ways of thinking about higher education”, as the Institute of Education’s Paul Temple recently wrote in Times Higher Education.

Student activism also began to gain ground, notably in the events of 1966 and 1967 at the London School of Economics but spreading to Essex and beyond. Fred Inglis, who graduated from the University of Cambridge in 1960, has argued that there “were more committed students than at any other time. Never before or since was there such a sense of keen exchange.” Margaret Thatcher took a rather different view. She wrote in her 1995 memoirs, The Path to Power: “The universities had been expanded too quickly in the 1960s. In many cases standards had fallen and the traditional character of the universities had been lost.”

I was raised in Cheam, in Surrey, where Tony Hancock did not live but Harry Secombe did. Cheam’s only advantage was that it felt superior to neighbouring Sutton where nonetheless I went to school. At the top of the high street was a private school where Michael Frayn was a pupil. When I later accused him of being privileged he pointed out that his school had a corrugated iron roof, obviously a piece of casuistry since he went on to be a prizewinning novelist and playwright while I went on to write for THE.

My father was opposed to my going to university on the grounds that he had succeeded without it. My mother wanted me to go to the University of Oxford. I even took an entrance exam. Unfortunately, one paper was in Latin, which I had been studying only for a day. I could decline the verb “to love” but the only noun I knew was “table”, and the likelihood of those being over-useful in a three-hour exam was doubtful. Unless my memory deceives me, one question on the general paper was: “Is a working knowledge of Latin useful for a gentleman?” For that, three hours was inadequate.

An unfortunate by-product of the 1944 Education Act was that while 19 per cent went to grammar school the other 81 per cent were thrown into a skip, a system Kent preserves to this day

I was a beneficiary of the 1944 Education Act. An unfortunate by-product of the Act was that while 19 per cent of the age group went to grammar school, the other 81 per cent were thrown into a skip, a system that to this day Kent preserves out of either nostalgia or a sense of postmodern irony. I wouldn’t be surprised if they still sent boys up chimneys. The year I went to university only 4.2 per cent of my age cohort did so, so there was another skip to hand for any who had escaped the earlier cull. At the end of that decade the number of universities had doubled, and over the next few years five Black Papers edited by Charles Brian Cox and A. E. Dyson offered conservative ripostes to the White Papers that brought about such changes. Contributors included Kingsley Amis, who, appalled at the idea of comprehensives, argued that “more will mean worse”. Ironically, two of the authors of those pamphlets ended up at the University of East Anglia, which definitely represented more, but I trust not worse.

Admittedly, unlike today’s students, betrayed by all three major parties, I did receive a grant, but it was minimal because my father refused to divulge his income. I earned money by filling a drinks machine on Victoria station as my friends made sandwiches. We decided to form a union. It was called VASTSWAMPSA (the Victoria Ancillary Services Trades Sandwich Wrappers and Machine Products Suppliers Association). I still have the tie.

In those days there was no Ucas: you simply applied to individual universities. I was interested in literature and economics, not really seeing much distinction since both seemed to specialise in making things up. The problem was that I forgot which subject I had applied for. When I went for an interview at the London School of Economics, where you could study both, I had to let the interview develop in the hope that they would inadvertently reveal what I was supposed to enthuse about.

I went to the University of Sheffield, which was something of a shock. In Cheam, neighbours of 30 years were referred to by their last names. In Sheffield, 16-stone bus conductors would call you “luv”. My teachers were either brilliant or in need of secure accommodation, for the most part both. My biggest shock was to discover that in the first year of my English degree I would be obliged to study Latin. By then I had mastered “Caesar, having pulled the boats up on the shores of Gaul”, but somehow I doubted that would get me through, more especially since I was also required to learn Anglo-Saxon. So, not one dead language but two. They had high standards at Sheffield, though. The year I graduated, the history department gave its first first-class degree in 15 years. I plainly could not have passed first-year Latin but somehow did. Perhaps I had hit upon a lover of Caesar and his energetic relationship to boats.

I later spent a year at a university in America where the 1960s had supposedly been invented, except that I lived in Kansas where as a foreigner I was required to take an English-language exam and repeat all my inoculations on the grounds that the originals had been carried out by the NHS, which was regarded as essentially a communist organisation. I responded by accidentally dropping an air-conditioning unit out of the window of my fifth-floor apartment.

Today, people feel nostalgia for a decade they never experienced. The 1960s are celebrated as if everyone had been slouching towards Woodstock or easy riding on lysergic acid diethylamide. Well, that was the Sixties for everyone – except for those for whom it wasn’t. In some halls of residence it was forbidden to lock doors for fear of what might happen behind them. In truth, we just removed the door handles.

John Gilbey

Between 1960 and 1970, the number of graduates more than doubled. By 1970-71, there were 236,000 students studying at universities and 204,000 at polytechnics, and the higher education participation rate had reached 8.4 per cent.

John Gilbey, a science and science-fiction writer who lectures in IT service management at Aberystwyth University, graduated from the University of East Anglia in 1979, the summer after the “Winter of Discontent” and its widespread strikes by public sector trade unions. The decade also saw the launch of this magazine, which began life as The Times Higher Education Supplement in 1971.

The nightmare is always the same. A huge lorry backs up towards the übermodern glass-clad portals of the university library; after a hiss of air brakes the driver gets out and approaches the porter on duty by the turnstiles. “Where do you want this lot, mate?” he asks, and the peak-capped porter jerks a thumb in the direction of the stairwell. “Downstairs with the rest of it, pal…”

I know it’s a dream because the lorry then backs past where the barrier was a moment ago, and the back of the lorry starts to tip. A torrent of books and bound journals pours from the tail-board and cascades down the broad stairs into the bowels of the library, each volume cartwheeling with a terrible momentum. Two floors below, in an atmosphere of chilled scholarly calm, my friends and I are poring over more of these tomes on the tables of the environmental sciences section. The dull roar in the distance announces the terrible truth, as the flood of literature rushes around the corner of the stairs. We wade waist deep through the angular deluge towards the exit – only to be engulfed and overwhelmed in the manner of a cheap made-for-TV disaster movie.

I was the first in my family to go to university, and my father’s experiences in engineering made him suspicious of graduates, or ‘Five Minute Apprentices’ as he called them

Simple enough psychology, I guess, but this was close to the reality of undergraduate learning in the mid-1970s. The internet as we know it today was still a glint in the eye of science-fiction writers, and such computing resources as we had were still largely paper-based: either decks of punch cards or closely rationed time on a desperately slow and blisteringly noisy hard-copy terminal. If you needed current research you had to churn though the printed citation indexes, or riffle the crispy pages of the Current Contents copies that littered the coffee-room table. Little wonder that I still occasionally wake sweaty palmed after reliving that mental textual dam burst.

In some ways I barely recognise the hairy, unkempt figure that arrived pathologically nervous and self-apologetic at UEA – the University of Extraordinary Abbreviations – in the autumn of 1976. I was the first in my family to go to university, and my father was not wholly convinced of its value: his experiences in engineering had made him suspicious of graduates – or “Five Minute Apprentices” as he called them. He was equally unsure of my choice of subject; what was “environmental science” anyhow? It smacked of hippies, dodgy tobacco, tie-dye and whale-hugging. Although I’m told that I still dress like a homeless person and my hair has now receded to my chin, my three years in the wilds of East Anglia gave me a breadth of scientific knowledge that allows me to communicate effectively with the adherents of many narrower specialisms. The young, cheerfully reactionary faculty were strong believers in the value of fieldwork and I spent much of the long, cripplingly cold Norfolk winters digging soil pits, measuring river flows, prising unwilling arthropods from the turf of snowy heathland and dreaming of a job where I could make a real difference.

I managed to blag a place on a Natural Environment Research Council-funded expedition to Svalbard (skipping my graduation ceremony to celebrate my degree with a glass of malt whisky on a trawler in the North Sea, for which my mother has yet to forgive me) and spent a blissful 10 weeks as boatman to the party in the astonishing 24-hour daylight of Arctic summer, complete with polar bears. My father, an inveterate yachtsman, finally approved. At 21 I was absolutely convinced that I could save the planet, and only later realised just how much smarter I’d need to be to reach the lofty peaks of academia. When my satirical articles and science-fiction stories began to gain more – and better – feedback than my research papers, I realised that there is much satisfaction to be gained by making your life in the pleasant foothills instead – content to watch and record the fervid activity on the upper slopes from a safe distance.

Gillian Fowler

Despite Margaret Thatcher’s concerns about the 1960s expansion, higher education continued to grow after she came to power, although funding did not: the “unit of resource” fell by 47 per cent during the Conservative years (1979-97). In 1981, universities were given one month to make an average of an 18 per cent cut to their budgets. By 1985-86, there were 909,300 students in UK higher education. Gillian Fowler, a forensic anthropologist and a lecturer at the University of Lincoln, began her undergraduate degree in 1989 at what was then Edge Hill College of Higher Education. She graduated the year in which the Further and Higher Education Act 1992 abolished the “binary divide” between universities and polytechnics, and brought about the creation of a large number of “post-1992” universities.

I was the first person in my family to enter higher education and my mum was especially proud as she’d had to leave school at 15 to go to work in Boots. She wanted me to have the opportunity she had never had, and to be independent. The year was 1989 and Margaret Thatcher’s government had been in power for 10 turbulent years. During the three years of my degree, the Tories introduced the community charge, commonly known as the poll tax, which students were required to pay while studying, and the student loan system (to help with living costs). I also remember a huge students’ union campaign asking the big banks to cancel Third World debt. To make myself feel less guilty, I moved my bank account to the Royal Bank of Scotland, a smaller and more ethical bank – or so I thought.

There were huge changes to education in the 1980s, including the introduction of GCSEs in 1988. I know that because I was among the last cohort to sit O-level or GCE exams in 1987. During sixth form I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do, so I chose the subject that interested me most and the one which I was best at; today’s students seem much more focused on the vocational path and a degree is simply seen as the vehicle to get them there.

My selected institution was Edge Hill College of Higher Education. In 1989 it was a fairly small place compared with today, when it is home to more than ,000 students. The majority were from comprehensive school backgrounds and had, shall we say, deviated from the path of achieving good grades at A level. Many were on full maintenance grants and, back then, tuition fees were fully funded by the local education authority. Most were training to be teachers, although some, like me, were taking degree courses unrelated to that.

My subject, geography, was taught in what I can only describe as a hut just off to the left of the vast lawn in front of the magnificent edifice that was purpose-built in 1933 for female teacher trainees. As was the case in 1933, all my assignments had to be handwritten; there were no IT facilities, although I do remember microfiche readers in the library. You were expected to take notes in lectures, so if you missed one you had to rely on a friend to catch up. Nowadays, of course, students can languish in bed and view the relevant PowerPoint at a more convenient time than 9am thanks to universities’ virtual learning environments. Like most first-year students, I lived in halls; mine was just for women, another throwback to 1933, and the whole corridor shared two toilets, about five shower cubicles and a few hand basins – slightly different from the en-suite luxury students in halls experience today.

I don’t think I would recognise the place now, and I have never been back since graduating during the 1992 recession. I had already decided to take a year off and travel a bit; it was difficult to get a graduate job back then but it didn’t seem to matter where your degree was from. Students today probably face more pressures than my generation, not least an even bigger recession. Today’s undergraduates coming to the end of their first years are paying up to £9,000 and will leave heavily in debt, so we have begun to see subtle changes in their expectations about value for money. I hope these changes will lead to ever-rising standards, but I also hope that we do not forget what should be at the heart of every university: the love of learning.

Shahidha Bari

In the wake of the 1997 election victory by Tony Blair’s Labour Party, upfront tuition fees of £1,000 were introduced in 1998-99 for all but the poorest students via the Teaching and Higher Education Act 1998. Shahidha Bari, now a lecturer in Romanticism at Queen Mary, University of London, began her undergraduate study the following autumn.

A key objective for Labour was widening participation, encouraging more students from under-represented groups to go to university, and in 1999 Blair declared his ambition for 50 per cent of the UK’s 17- to 30-year-olds to enter higher education. “In today’s world there is no such thing as too clever. The more you know, the further you will go,” he said.

In 2000, the media shone a spotlight on an issue that would prove to be a recurring concern: the fairness of university admissions. The Laura Spence affair hit the headlines after Gordon Brown criticised Magdalen College, Oxford for rejecting an application from Spence, a well-qualified comprehensive school pupil who went on to study biochemistry at Harvard University (and later medicine at the University of Cambridge). Her rejection by Magdalen served as a lightning rod for complaints about Oxbridge’s apparent bias against state school students.

In 2002, Tom McLellan overslept and missed our graduation ceremony, much to the distress of his fond and diligent parents who had travelled to Cambridge from the Midlands. This, and the wild rumour that Jack Nicholson had been spotted strolling the college grounds (not true – Anna Kessel had a wolfishly cool-looking grandad) were the two big stories of the day. Along with a photo of my parents, pleased and poised on a verdant college lawn, those are my main memories of graduation.

My parents were not intimidated by Cambridge airs. Hard-working immigrants with no sense of entitlement other than that won by their sacrifice, they were parents to be proud of

My parents were no more proud than any others. I’m sure, in fact, that I was more proud of them than they of me. My father, severe and handsome, and my mother, capable and polite, had a certain grace. Unfazed, they were neither impressed nor intimidated by Cambridge airs. They had their own. Typically hard-working immigrants with no sense of entitlement other than that won by their sacrifice, effort and discipline, they were parents to be proud of. They were ambitious for their children and their quiet confidence held me in good stead when I started at King’s College, Cambridge in 1999.

In one sense, Cambridge, as I remember it, was oddly meritocratic: demonstrable intelligence trumped social grace, beauty and privilege. King’s kids were either precociously “musical” or painfully “political”, and everyone had Grade 7 in violin and/or Labour Party membership. The college was largely populated by the comfortably middle-class children of health professionals and minor academics, with a scattering of Euro aristo-trash and Eton choral scholars. We were the Cool Britannia brigade (although we would have been indignant at this label): post-Spice Girls, pre-9/11, kicking around, waiting for the internet to take off. We were privileged and in denial, sniffing out the merest excuse for a sit-in, a face-off or a booze-up. It was glorious and I only vaguely knew it. When I came back to Cambridge for my final year in October 2001, the US had invaded Afghanistan. The bookish bubble of Cambridge was a sanctuary still, but I had some idea that the outside world into which I was about to enter had been tipped on its axis.

I studied ravenously at university, ostentatiously seeking out the Divinity and other exotic libraries, and ordering expensive architecture books on the college account – nobody seemed to mind. I can condemn Oxbridge elitism with the best of them, but I also know that it was a place where intellectual enquiry flourished because of the funds that flowed into it. It’s what I would want for all universities. All students should have access to the kind of resources, connections and cultural capital Cambridge gave me. It’s one of the reasons I’m a trustee of Arts Emergency, a charity that mentors young people pursuing an arts education.

University formed me, but it also matters to the people I love best. For my mother, my success was a quiet confirmation of her own never-realised intellectual potential. My nephew, Zak, who likes “some” books, knows I teach at a “big school” to which he might like to go. My partner, whose own languid Just William-ish schoolboy delinquency mainly consisted of petty arson and commandeering abandoned tractors, is, I think, quietly reverential at how rapidly I repair his nightly Guardian crossword bodging. Cambridge made me good at crosswords; it imbued me with confidence and an ability to work quickly. The year I started, £1,000 tuition fees had been introduced and grants abolished. I baulked at the debt that came with my degree. I know now that my education meant much more than this, but I worry that the crippling levels of debt students now face will deter those for whom a university education could mean the most.

Kathryn Felton

In January 2003, newspapers reported Labour’s plan to introduce top-up fees of up to £3,000, which were to be paid via loans and repaid after university. “Mr Blair remains convinced that some universities will no longer be able to compete in an increasingly competitive world market unless they are able to increase their income,” The Guardian reported. Top-up fees were introduced in the 2006-07 academic year after a bloody political battle and student marches – both of which were repeated on a bigger scale when Parliament voted in December 2010 to treble the cap on tuition fees to £9,000 from 2012-13.

Meanwhile the economic downturn has brought an ever-greater focus on employability as universities and graduates confront the prospect of rising youth unemployment.

Kathryn Felton, 23, has just finished her degree at the University of Roehampton, where she studied drama and journalism.

Is it worth it?” This is the question my 17-year-old brother asked me in September when he was thinking about applying to university – and it’s one that is being asked up and down the country in the era of £9,000 tuition fees.

For me, the decision to go to university was more than simple progression from college. I had taken two years out of education following A levels, but I decided to abandon a career in journalism because of the distinct lack of opportunities for unqualified or inexperienced writers in my area, West Sussex, as the recession hit.

So to London, the centre of news production, I went. At Roehampton I took modules in theatre criticism and critiqued films and books on a blog. I became addicted to Twitter and learned how to use it to my advantage.

Most importantly, I studied law and ethics in journalism, and in my spare time spent hours reading the reports of the Leveson inquiry. This has inspired me to pursue a career in media law. From September I will be studying part-time for a graduate diploma in law at BPP University College.

It was great to have time to explore other interests. During my two years of full-time work, I managed amateur dramatics rehearsals twice a week. At Roehampton, I was suddenly able to rehearse, work, study, play netball, organise and help run the debating society, sit on the university senate, produce two shows on Fresh Air Radio, and still have time to drink and dance the nights away (provided I made up for it with a night-long session in the library).

Extracurricular activities at university are no longer the pursuit of the geeky/sporty few, nor are they only for fun these days. Many students now recognise the need to stand out if they are to achieve success after they graduate. Youth employment rose to more than 1 million while I was at university. My peers took up internships, attended auditions, volunteered for charities with vague links to the fields they hoped to enter, and all this while studying hard. The tactic can pay off: one friend now has a dream job through a contact she met while writing for the university newspaper.

University can be an excellent springboard. The staff on my course had top-notch contacts and all my lecturers were part-time or ex-professionals. Thanks to that, suddenly you can find yourself being given the opportunity to speak to the very person whose job you want more than anything.

Was it worth it? I would pay five times as much to do it all over again.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?