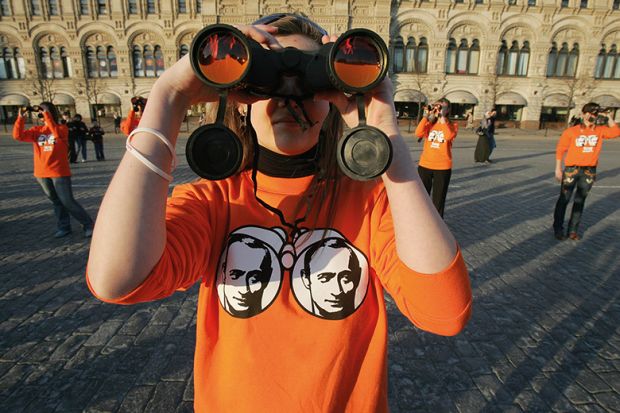

The Russian government’s move to restrict researchers’ interactions with foreigners has been seen as the latest shift towards science nationalism around the world, and potentially as a sign of the emergence of an alternative set of norms around academic freedom, no longer governed by “Western” values.

An order issued by Russia’s Education Ministry in February, which came to light this month, dictated that all scientific organisations must notify the ministry about planned meetings with colleagues from abroad and that at least two Russian scientists must be present at such gatherings. After one of these meetings, Russian academics must now file a formal report summarising the conversation and including copies of all participants’ passports.

Foreign scientists visiting scientific organisations in Russia are also now forbidden from using any recording or copying devices, except “in cases stipulated by Russia’s international treaties”.

Following outrage from academics, the ministry said that the measures should be seen as recommendations that take into account the growth of international relations. Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov told Reuters that, although the directive sounded excessive, it was important for Russia to be wary of foreign espionage.

The move comes amid US universities’ increasing reluctance to collaborate with Chinese academics, prompted by anxiety about intellectual property theft.

In what may be a linked development, China and Russia have been building stronger research ties, triggering suggestions that the region may move towards a new set of standards characterised more by state control and less by freedom of intellectual enquiry.

Isak Froumin, head of the Institute of Education at Moscow’s Higher School of Economics, said that he would “expect to see more and more such [policies] in different countries”, including Western nations, “because we are moving to a strange era of growing isolation and declining cooperation”.

Anatoly Oleksiyenko, associate professor in higher education at the University of Hong Kong and co-editor of a recent book on the Soviet legacy in Russian and Chinese universities, said that the new guidelines reflect Russia’s “radical shift towards re-Sovietisation” of higher education, adding that “surveillance and mistrust have returned to the academic workplace”.

Dr Oleksiyenko said that “young researchers in the post-communist societies are most vulnerable these days” to academic freedom attacks.

“They once believed in and committed themselves to a democratic future, which was promised to them by post-Soviet reforms. Then, over the last few years or so, they unexpectedly confronted the repressive regimes that sought to restore a quasi-dictatorial environment. The revisionists are increasingly revengeful,” he said.

Academics have debated how influential increasing cooperation between Russia and China in higher education will prove. Although the proportion of Russian research co-authored with academics based outside the country fell from 28.2 per cent in 2013 to 23.6 in 2017 – with observers blaming the country’s political stand-off with the West – the number of co-authored publications involving Chinese and Russian academics increased by 95.5 per cent between 2013 and 2017.

Marcin Kaczmarski, lecturer in security studies at the University of Glasgow, said that the “overall level of administrative control over higher education has been growing” in Russia and may increase further as a result of the country’s growing ties with China.

“It is not impossible that in the future increasing contact between Russian and Chinese bureaucracies leads to sharing ‘best authoritarian practices’ and generates temptation on the part of Russian bureaucracy to follow China’s strict control over academia,” Dr Kaczmarski said.

Witold Rodkiewicz, senior fellow in the Russian department at the University of Warsaw, said that Russia has “been very interested by and attracted to Chinese authoritarian practices”.

“There is an increasing frequency of visits and consultations between Russian and Chinese establishments and the Russian regime eagerly develops contacts and ties in the higher education sphere,” he said.

However, Dr Rodkiewicz said that academic freedom has always been under attack “from very disparate quarters”, and questioned the notion that the latest developments in Russia were signs of shifting norms.

“In the West we have our own problems with academic freedom, but they are different in nature than in Russia or China – bureaucratisation, commercialisation, democratisation and so-called political correctness,” he said.

Margarita Balmaceda, professor of diplomacy and international relations at Seton Hall University in New Jersey, said that Russia has seen a “steady shift in attitudes and norms concerning the role of the state in university and research life”.

However, she said it was surprising that the new guidelines co-existed with “very clear goals of the Russian Education Ministry to significantly increase the visibility and ranking of Russian universities”.

“In the past few years, this goal has been pursued, among other ways, through the hiring of foreign scholars – on both short- and medium-term contracts – for research positions,” Professor Balmaceda said.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Russia joins global shift to science nationalism

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?