Browse the full Times Higher Education Europe Teaching Rankings 2018 results

European universities that produce a high volume of research and boast a strong teaching reputation tend to have the greatest gender imbalances among staff, according to data collected by Times Higher Education.

Analysis of data on over 200 universities across western and southern Europe shows that the correlation between universities’ staff gender balance and rate of publications per staff member is -0.57, where -1 is a perfect negative correlation.

The correlation between universities’ staff gender balance and academic teaching reputation (based on a survey of scholars) is less strong but still significant at -0.42.

The findings are based on data collected for THE’s pilot Europe Teaching Rankings, underpinned by 13 teaching-focused metrics gathered from 242 universities across eight countries.

It is the first major international university ranking to include indicators on the gender balance of staff and the gender balance of students. On these metrics, universities receive the maximum score of 100 for a 50:50 gender balance, while the lowest scores represent the biggest skews towards male or female staff.

Middlesex University in the UK, which ranks in the 201+ band overall in the Europe ranking (and is in the 401-500 band in the research-focused THE World University Rankings), is the only institution that has a 50:50 gender balance of staff. Unusually, its executive team has a 63:37 ratio of female-to-male staff, according to a spokeswoman at the institution.

Other universities that tend to be lower-ranked in research-focused rankings (or absent altogether) also do well on this gender balance metric, including Rennes 2 University in France (151-200 in Europe ranking), Hanze University of Applied Sciences in the Netherlands (151-200) and King Juan Carlos University in Spain (201+).

Meanwhile, some prestigious science-focused universities feature in the bottom 5 per cent on the gender balance metric, such as Eindhoven University of Technology (126-150), Technical University of Munich (51-75) and Imperial College London (joint 11th). The universities of Oxford and Cambridge feature in the bottom 15 per cent for staff gender balance; just 29 per cent of staff at both institutions are female.

Dame Athene Donald, master of Churchill College, Cambridge and the university’s former gender equality champion, said that the link between high publications, reputation and poor gender balance was “very worrying”.

“I fear stereotyping of women means that they are often expected or ‘encouraged’ into pastoral and teaching roles. These tend to score less highly in research-intensive universities’ promotion criteria,” she said.

“Hence, it looks as if women are either voting with their feet or being actively discouraged from staying in universities focused on research and publications, leading to this inverse correlation with gender balance.”

Benedetto Lepori, a professor at the University of Lugano specialising in research into higher education systems and coordinator for the European Tertiary Education Register (ETER), which compiles comparable data about individual higher education institutions across Europe, said that women “tend to have lower rates in terms of publishing”.

He added that the results may also be influenced by the subject mix of “top international universities”, which tend to “focus on sciences”, while those specialising in disciplines that generally have a high share of female staff, such as education or nursing, are typically lower-ranked.

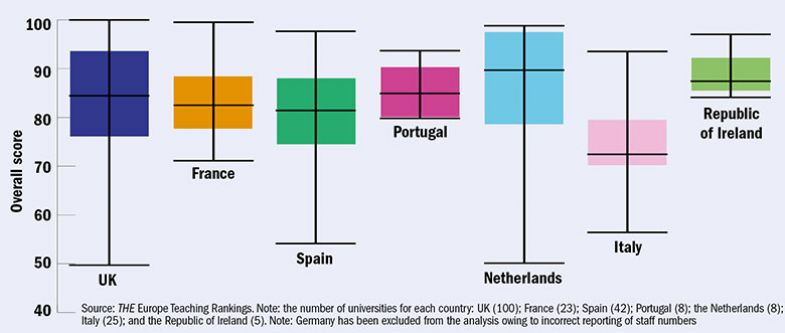

Country comparison: staff gender balance scores across Europe

Analysis of the data at a country level also shows that the strength of the correlation between gender balance and publications or reputation differs depending on the nation.

For example, in the UK, there is a very strong relationship between staff gender balance and publications (-0.72) and staff gender balance and reputation (-0.64). The UK has 100 universities – from old research-intensives to newer teaching-focused institutions – in the table.

In contrast, when looking at the 23 French institutions only, there is a strong negative correlation between publication count and staff gender balance (-0.55) but a very weak relationship between reputation and staff gender balance (-0.10). This may be due to the fact that several notable French universities are missing from the table, so there is not such a wide distribution in their academic reputation scores.

On average, countries perform similarly when it comes to the gender balance of their university staff, but Italy lags behind on this indicator (see graphic). The country receives a median score of 72 for this metric, compared with a median of 90 for the Netherlands and 84 for the UK.

Italy’s score is slightly lowered by the inclusion of four Italian polytechnics in the table, all of which receive lower-than-average scores on this indicator. But many of its traditional universities do not fare much better; if the four polytechnics are excluded from the analysis then the country still only receives an average score of 75 on this metric.

Davide Donina, postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Bergamo, who undertakes research on higher education policy and governance, particularly on the Italian sector, said that the “low level of hiring” in Italian universities over the past decade could have slowed down Italy’s progress in this area.

Universities now tend to hire an even split of female and male academics, which was “not the case in the past, so the ‘stock’ is unbalanced towards men”, he explained.

Professor Lepori said that the finding is backed up by the 2014-15 ETER, which shows that just 23 per cent of higher education institutions in Italy have at least 40 per cent of academic staff who are women. In contrast, “generally there are more female” staff in the Nordic counties and these nations tend to see women move into senior positions earlier in their career, he said.

The rankings data also show that there is a strong positive relationship between academic teaching reputation and publications per staff member.

While academics were asked to name the best teaching universities in Europe in their field for the reputation survey, the finding seems to illustrate the halo effect of research performance and that scholars still rely on research metrics when judging teaching quality.

Gero Federkeil, head of international rankings at the Centre for Higher Education Development, a German thinktank, said that data from its national ranking of German universities also show that “measures on teaching reputation among academics are highly correlated with research performance”.

“On a global scale, they simply do not know much about the quality of teaching and generalise their views on research,” he said.

Professor Lepori agreed that “most scholars” still assume that “if somebody is very good in research, the quality of teaching will be very good”.

There is also “no hard data on the quality of teaching”, he added.

But, the publication of the THE Europe Teaching Rankings, which includes five metrics directly related to student engagement (based on a survey of students across Europe), aims to challenge that.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: European elites have the ‘worst gender balance’

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?