The introduction of lecture capture has proved, like most technological innovations in higher education, controversial.

Debates over the merits of recording lectures and making them available online for students have ranged from the issue of who retains copyright of the content to the divisive use of pre-recorded lectures to provide “tuition” during strikes by academics.

Online recordings can allow students to watch missed lectures – invaluable for those absent because of ill health or those who have disabilities that make attendance on campus difficult – and to use them for revision, which is particularly beneficial for students who have learning issues or struggle with the language. The footage can also serve as a study aid in a flipped classroom set-up.

But critics say that the recordings encourage students to skip lectures and damage the overall attainment of those who rely on them because recordings can lack the personal engagement that frequently drives learning.

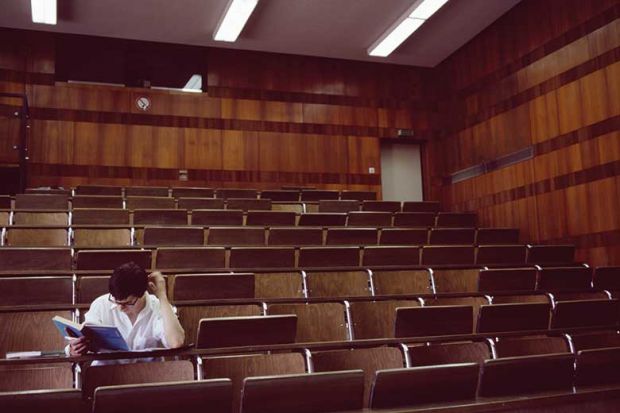

Anecdotally, some academics have reported that introducing lecture capture has caused attendance rates to drop. Melanie O’Brien, a senior lecturer in international law at the University of Western Australia, told Times Higher Education that since lecture capture was made compulsory at her institution, attendance to lectures in her department has plummeted. “One colleague with 150 students enrolled has lectured to 15 students. Three of us have lectured to empty rooms,” she said.

Social media has been awash with posts from academics sharing similar negative experiences, but contrasting views have been equally well represented. The academic literature on the subject is much the same: a number of studies report that the introduction of lecture capture has had a negative effect on attendance, while others reveal no correlation.

In a paper published earlier this year, researchers at King’s College London found that the introduction of lecture capture on one course was followed by a doubling of the number of undergraduates who did not attend any lectures – and also a doubling of the proportion of students who skipped all classes, to 40 per cent. A 2009 study in Canada of nearly 900 students found that 37 per cent of them said that their attendance was affected by lecture-capture availability, and a 2013 University of Birmingham study reported a decline in attendance at lectures from 84 per cent to 71 per cent after lecture capture was introduced.

In contrast, a new study led by Emily Nordmann, a psychologist who has recently moved from the University of Aberdeen to the University of Glasgow, found “no compelling evidence” of a relationship between attendance and recording. The study, accepted for publication in the journal Higher Education, says that it was the first to look across four years of an undergraduate programme and that it found “no negative effect of recording use”.

Other studies have reached similar conclusions. Computer scientists at Queen’s University Belfast who monitored the introduction of lecture capture on their courses judged that it had not harmed attendance and reported that students had used the footage to aid their learning, according to a 2015 paper. Meanwhile, a Solent University study released the same year found that 79 per cent of student respondents said that lecture capture would not encourage them to skip lectures.

One big problem is that the majority of research into lecture capture relies on self-reported data, indicating students’ intent to not miss lectures, rather than information about actual student behaviour. Some recent studies, such as the ones undertaken at King’s and Aberdeen, have tried to overcome this by comparing attendance and attainment before and after the introduction of lecture recordings.

Other research efforts have focused on the relationship between how students use lecture capture and the grades that they achieve. A 2015 lecture capture literature review, by Gabi Witthaus and Carol Robinson for Loughborough University, identified a 2012 Australian study that showed that students who substituted viewings of recorded lectures for physically attending were found to be at a severe disadvantage in terms of their final marks; “moreover, those students who attended very few live lectures did not close the gap by watching more online”, it said.

Although several studies have found no negative correlation between use of lecture capture and attainment, these have sometimes focused on cases in which students have used the footage to supplement their existing learning activities.

“Simply logging on to a recording does not equate with engagement with material,” said Michael Draper, an associate professor of legal studies at Swansea University, who conducted a study that found that lecture capture did not harm attendance.

The 2013 Birmingham study, which reported that even high usage of lecture recordings did not have a significant impact on academic performance, took a balanced view. “Overall, this approach appears to be beneficial, but may reduce lecture attendance and encourage surface learning approaches in a minority of students,” the researchers said.

Martin Edwards, who led the King’s research, said that even if a minority of students say that they will not attend lectures because recordings are available, that can still translate to a sizeable portion of the cohort suddenly going absent. Dr Edwards pointed out that even Dr Nordmann’s study found that the one course that did not have lecture recordings had significantly higher attendance than those that did have recordings.

He added that when talking about whether lecture capture had a positive influence on students, it was important to note that there was a difference between the introduction of lecture capture and its effect on attendance, and lecture-capture viewing and its effect on attainment.

“The people who are so-called deep learners will attend lectures and use lecture capture to boost their study, so it won’t have a negative effect on their attainment. The problem lies with the introduction of lecture capture, which the overall evidence shows does translate to a drop in attendance, and those ‘surface learners’ who watch lectures online instead of attending,” he said.

The literature review also highlighted a 2013 Canadian study that showed that students who were identified as surface learners tended to report missing more lectures and using recordings as a replacement for lectures, whereas deep learners tended to use the recordings as an extra resource, to help with revision, for example.

“The evidence shows that students who choose not to go because they rely on lecture capture will struggle to keep up, and that’s a real problem; it can potentially disadvantage certain types of learning styles,” Dr Edwards said.

Dr Nordmann said that she believed the key takeaway from her study to be not the lack of a relationship between lecture capture and attendance or attainment, but rather the revelation of just how many different things impact attendance. “It’s actually really difficult to draw these big conclusions about the effect of lecture capture based on individual studies. You have to look at the literature,” she said.

Most studies are a snapshot of one course at one level of study, Dr Nordmann continued. “Even in our study that looked at four years, we found that there was a difference in attendance between two recorded courses in the second year, and I think the reason for it was that one of the topics was more popular,” she explained.

“Currently, studies are only ever comparing a recorded course and a non-recorded course in one discipline. But if you compare your recorded courses, you will find a difference in attendance; that’s a really strong signal that it’s not just about the recordings,” she said. “You can’t say lecture capture is good or bad, it’s how it is being used and who it is being used by.”

Lecture capture is already a fixture in higher education around the globe. Its use is widespread, and many institutions are joining Western Australia in making it compulsory, including De Montfort University and the University of Huddersfield in the UK.

“Lecture capture is here to stay,” said Swansea’s Mr Draper. “In a short space of time, students are so used to the system that they are likely to complain if it is not available.”

However, he cautioned that it must be integrated as part of a strategy “that seeks to support students in their studies or as part of a blended learning programme, rather than an immediate substitute for traditional learning though face-to-face contact”. At Swansea, for example, the policy is to “wipe” the lectures at the end of the year and to give lecturers the choice to opt out, he added.

For Dr Nordmann, the most important thing is to start providing guidance for students. “We give them this technology but don’t tell them how best to use it,” she said. They need to know that supplementary use is best and not to use it as a substitute for in-person lectures, she added.

Most universities offer online courses, so it’s not illogical for students to believe that that is how you can use recordings, Dr Nordmann continued. “We need to be making the case for attendance and lecture capture as a supplemental technology in a way that we aren’t now; we’re complaining about attendance but not doing anything to guide the students.”

Dr Edwards added that one of the ways to counteract the drop in attendance was to ensure that lectures provide something special that cannot be replicated in a recording. If lectures are interactive – employing in-class polls, for example – students get something more from being present in the room, he said.

There are good arguments for why all lectures should be recorded, particularly for students with special educational needs who require some extra help, he said. “The problem is, there will be a proportion of the cohort that will not go because there is a recording of it.”

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Watch and learn? Lecture capture gets mixed reviews

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?