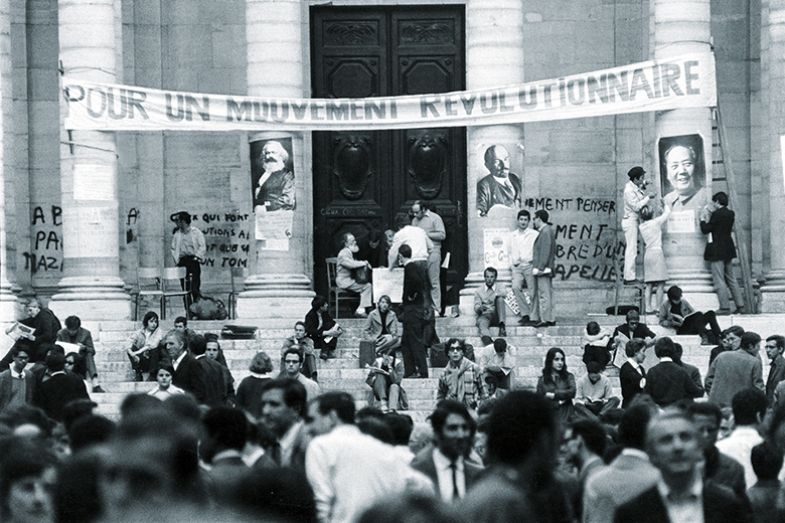

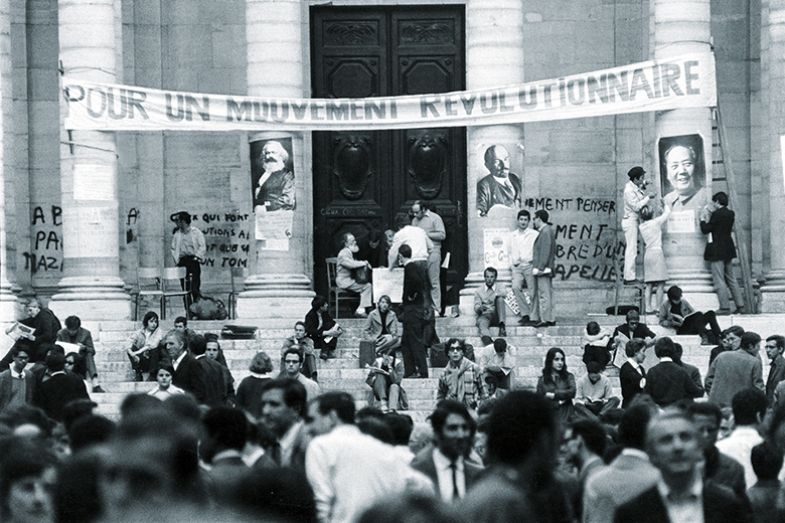

Rather than merely commemorating the events of 1968, France appears to be staging something of a re-enactment. Fifty years ago this month, the events of that iconic year reached their crescendo with the mass protests in Paris by students, trade unionists and public sector workers against the direction the Gaullist government was taking the country. As one of the articles we present in this piece explains, that trajectory included a more focused, business-facing higher education sector, with student admission based on academic merit.

Those reforms ultimately perished in the conflagration, but the plans of the current French president, Emmanuel Macron, to reform the French economy and higher education system – including the introduction of selective university admission – have provoked protests that have consciously evoked 1968.

Universities have once again been occupied, including Macron’s alma mater, Sciences Po, and Sorbonne University, the epicentre of the 1968 protests. Macron has suggested that the modern protesters were actually “professional agitators” and their relatively small number – 80 in the case of Sciences Po, 200 in the case of the Sorbonne – certainly do not bear comparison with 50 years earlier. Either way, the publicity that the protests have garnered suggests that the legacy of 1968 remains potent in France.

But it is important to recall that 1968 was not all about France. Forces of protest and revolution were on the rise across the world, all broadly focused on overturning the powers of elites. As one of the pieces we feature here reminds us, nowhere was that aspiration realised more virulently than in China, where Mao’s Cultural Revolution, launched two years previously, was in full, murderous swing. The US, too, was gripped by huge protests against the Vietnam War and for civil rights. As another piece in this article suggests, something of the spirit of ’68 can also be seen in modern American protests, such as the anti-Trump Women’s March and high school students’ protests against permissive gun laws and their role in school mass shootings.

While many comparisons have been made between the present era of populism and the 1930s, it is clear that those interested in learning from history should also keep 1968 in mind.

‘Three characteristics of 1968 might resonate today: possibility, risk and joy’

Students have occupied a university building in Paris and others are marching on Washington DC. In the UK, academics are on strike. These are scenes not from 1968, but of the spring of 2018.

Times change. We live in a very different age from the tumultuous 1960s, epitomised by the signature date “1968”. Even so, universities and schools are still places where broader social tensions are felt and where people are agitating.

Fifty years ago, the world was aflame. Young people in the West, behind the Iron Curtain and in the global South were the loudest voices championing the values of equality, fairness and justice. Everywhere, people demanded accountability from institutions and governments. From anti-colonial optimism to participatory democracy, confident beliefs in the forward march of history reigned amid what one commentator has called “the first global rebellion”. To be sure, history is always messier on the ground and in retrospect, we can see more clearly many of the delusions and excesses of the 1968 generation. Still, there is no getting around the fact that the 1960s was a time of great upheaval and change.

Today, there is less confidence about the overall direction of history – where we are and where we are going. The mood of student and teacher mobilisations is more often defensive, epitomised by the French slogan ZAD – zone à defendre (“zone to defend”). In France, students reject Emmanuel Macron’s proposals to make university admissions more selective and perhaps less fair. British university employees strike to preserve their pensions, just as students protested against higher fees in 2010. American high school students fight to survive the school day in the face of absurdly permissive gun laws, while their teachers strike for better wages and postgraduates try to unionise. Defence of the social minimum seems more moderate than some of the grand, even revolutionary, ambitions of 1968.

Nostalgia tempts us to look back and mull how things were better before. Some who lived through the 1960s continuously fall into this trap. There is a dash of wisdom in the call to “forget ’68”, as the former Paris student-leader-turned-politician Daniel Cohn-Bendit said a decade ago. The past is past. Holding up 1968-era activism as a gold standard leads to inevitable disappointment, since the present can never recapture the splendour of the good old days. Yet beyond the ultimately false choice between fawning nostalgia and forgettable history, we might consider the powerful analogies between the 1960s and our own time: the similarities amid differences.

Now, as then, wealth abuses, violence harms, institutions exclude and people all over the world hunger for equality, fairness and justice. Now, as then, organising friends and fellow citizens requires hard work. The point bears repeating: organising is hard. It requires commitment, discipline, sacrifice and persistence.

Today, social action demands changing how we think about time: rising above the infinite instants of our smartphones to seek inspiration from the past in order to imagine a better future – one that we might never enjoy but whose image serves as a guiding star.

Three characteristics of 1968 might resonate today: possibility, risk and joy. It was Otto von Bismarck, of all people, who defined politics as the “art of the possible”. While we may lack compelling, big-scale philosophies of history, imagination is an ever-available resource – “what is” is only one version of “what can be”.

Beyond vision, further steps are necessary. First, we must face the risk of speaking up for what is right. Challenging unfair and unjust arrangements can have personal and professional repercussions. Young activists in 1968 were also afraid. Then, some rose to the moral and political challenges of their time, just as others are rising now.

Politics involves persuading people to do things differently, as well as knowing when – and when not – to compromise. Power is complex, never simply us-versus-them. Solutions create new problems and there is no perfection, only the least bad. But there is a need to temper impatience and frustration with this situation through a basic insight: that the experience of working with others is as valuable as any goal pursued. There is a joy in belonging to a community based on hope and inclusion, striving for the freedom of others.

Just as some of the challenges of the 21st century resemble those of 50 years ago, so a basic aspiration remains constant: the search for equality and plurality on a global scale, one local scene at a time.

Julian Bourg is associate professor of history at Boston College.

‘Contemporary left-wing identity politics is reminiscent not just of the student activism of 1968, but also of that other cultural revolution’

It is fair to say that 1968 became the symbol for the entire cultural upheaval of the 1960s, with its campus protests, hippies and radical activism. My parents’ generation looks back at it with pride, nostalgia and compassion. There is plenty of critical reflection, too, but blind spots remain. As a sociologist based in China, I feel called on to bring up the somewhat forgotten totalitarian brother of the West’s 1960s revolt: Mao’s Cultural Revolution.

This ran in parallel and interacted with the 1960s revolt in the West, which also turned against cultural elitism and the bourgeois university in the name of democratic equality. Students occupied Peking University and the University of California, Berkeley in the same period. While China intensified its war on “bourgeois” styles, California had her “summer of love” in which people cast their fancier clothes aside for T-shirts and shorts and turned their unpretentiousness into something of a political ideal.

Of course, there were crucial differences between the two cultural revolutions. How could it be otherwise, given that one unfolded under communist totalitarianism, the other within Western democracies? Both followed a wider trend in international socialism, however, that shifted the revolutionary focus from the economy to culture.

Mao believed that despite the economic collectivisation, there was still too much traditional and bourgeois-elitist culture around. To create a truly egalitarian society, all cultural and intellectual refinement had to be erased, because through it the old, oppressive inequalities reproduced themselves. Red Guards of students were encouraged to intimidate “bourgeois” teachers, intellectuals and administrators. All victims, including many party members, were good communists in name, but they were said to be unconsciously bourgeois, maintaining the old oppressive structures through microaggressions. The closest analogy would be the way that whites, according to the latest radical activism imported from the US, systematically oppress non-whites by means of their unconscious “white privilege”. The person accused of acting on “white privilege” – or, in China, “bourgeois splittism” – will only prove the accusation by denying it.

The offspring of formerly wealthy families had to fight against their mentality of privilege, but they could never completely rid themselves of their inherited guilt. Some Red Guard factions sang: “The son of a heroic father is always a great man; a reactionary father produces only bastards.” Contention remained, however. Whereas the children of cadres benefited from a deterministic linkage between one’s family background and political virtue, many children of parents deemed politically incorrect argued, by contrast, that they could transcend their inheritance through extreme loyalty to Mao and his ideology. They formed their own, extra radical Red Guard groups to compensate for their inherited collective sin.

The ensuing violence began in educational institutions. On 13 June 1966, Mao ordered all schools and universities to suspend their teaching so that students could focus on activism. On 18 June, faculty and party officials were publicly humiliated at Peking University. The first registered death occurred on 5 August at a Beijing girls’ middle school. The girls beat their 50-year-old headmistress with sticks and belts, poured boiling water over her and forced her to carry heavy stones back and forth, until she collapsed. The authorities were in tacit agreement.

The terror spread quickly. In schools and universities throughout China, teachers and administrators were intimidated, beaten up or driven to suicide. In the campaign against the Four Olds, Red Guards terrorised writers, artists and the educated. They destroyed furniture and old books in the homes of formerly wealthy families and vandalised ancient temples and other historic buildings and artefacts. Meanwhile, old streets attained new revolutionary names. All of it served to revoke, denigrate and erase the past.

In the West, many leftist intellectuals, artists and politicians at the time swooned. Over time, however, it became increasingly clear that Mao’s identity politics had resulted in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people and a general debilitation. It is therefore understandable that the activist family nowadays pretends that the Cultural Revolution never really belonged to it. Only a few staunch doctrinarians, such the French philosopher Alain Badiou, continue to identify with Maoism.

The left-wing activism that emerged during and after the 1960s broadened the focus from the emancipation of workers to that of women and ethnic, sexual and religious minorities. This, in itself, is laudable. The problem is that the old Marxist deceptions resurfaced in new forms: paranoid stories about unconscious systematic oppression, microaggressions and inherited collective guilt; crusades against historical monuments; and an obsession with dividing individuals and groups into oppressor-oppressed binaries.

Such overly rigid dichotomies – whites and blacks, men and women, “cis-gendered” and LGBTQ – play different groups against each other and deny the messy, complex and invariably non-binary diversity of uniquely assembled individuals. Contemporary left-wing identity politics is reminiscent then, not just of the student activism of 1968, but also of that other cultural revolution. If collective inherited guilt flows through anyone’s veins, it is the Red Guard blood in our contemporary campus activists and their elite instigators.

Eric C. Hendriks is a Dutch sociologist working for Peking University and the University of Bonn.

Source: Getty

Source: Getty

‘The institutional break-up of the old French universities allowed the creation of new groupings based on disciplinary, epistemological and also political affinities’

The mobilisation of French students did not begin in May 1968. Despite a decline in student unionism since the end of the Algerian war in 1962, the Vietnam War and the fight against American imperialism were the subject of several important demonstrations from 1966 onwards. And demands for the free movement of students between female and male university dormitories also resulted in protests from 1962 onwards.

But it is really from the beginning of the academic year 1967-68 that students began mobilising against higher education reforms. The “Fouchet reform”, which aimed to tailor university courses to the needs of the labour market and to introduce two-year as well as four-year degrees, led to protests both at universities and secondary schools. The question of equivalence between the old and the new system of studies also posed practical problems, and the lack of staff disrupted a large number of lectures.

Then there was the spectre of selective university entrance, proposed by the “reform Peyrefitte” and due to be introduced at the beginning of the next academic year. This was the Gaullist regime’s response to the rapid growth in the number of students in France, from 140,000 in 1950 to 270,000 in 1960 and more than 600,000 by 1967. This rapid rate of expansion posed practical problems, especially within the limited premises of the University of Paris.

Demonstrations exploded across France, reaching an unprecedented scale by 3 May 1968, with the evacuation of the Sorbonne by the police. From 12 May, an occupation of several French universities began, encompassing a very rich collective reflection, by both students and teachers, on issues such as national and interdisciplinary links. Their aim was to shape an alternative university project, taking in pedagogy, curricula, governance and social function.

But their biggest concern was for the democratisation of studies. Inspired by sociologists Pierre Bourdieu and Jean-Claude Passeron, whose 1964 book The Heirs: Students and Culture had denounced social reproduction in higher education, the protesters’ “pedagogical committees” proposed the establishment of “contracts” between teachers and students, making explicit what evaluation criteria would be used and asking teachers to mark only subjects that they had taught themselves. The committees also called for the introduction of a multidisciplinary “common core” in order to give students time to choose their subsequent specialisations.

Exam cramming was denounced as creating “force-fed geese” and the committees wanted to see examinations replaced by continuous assessment, based on personal research. More broadly, the aspiration was for universities to train a critical spirit, rather than becoming factories producing workers for the economy. The committees affirmed higher education’s vocation to research and reflect; to this end, universities needed to accommodate everyone, without entry conditions: hence the demand for a “popular university” that was “critical” and “open to workers”.

The protesters also denounced the dualism of the French higher education system and called for the suppression of the grandes écoles. And a new method was demanded for the recruitment of academics, based on their teaching experience as well as their publications and academic credentials.

This attempt at a collective redefinition of the university model, of a scale never before seen in France, made academics into a significant collective player in higher education policy, and politicians were forced to take note. A new law was passed in November 1968 that established the representation on university councils of teachers of all ranks, as well as students and administrative staff, all of whom had previously been excluded.

It also endorsed the demand for “multidisciplinarity” by stimulating the creation of universities bringing together faculties that had previously been largely independent of each other. And it recognised the merits of financial and scientific autonomy for universities.

In addition, considerable funds were made available to create new teaching, administrative and research positions, and to offer more scholarships for students, more places in university residences and more meals in university refectories. Capital budgets were increased by nearly 19 per cent, allowing 33,000 additional student places through a mixture of new build, relocation and the transformation of university colleges into true universities.

Among the fruits of the building programme were experimental university centres at Dauphiné and Vincennes, which shared the principles of multidisciplinarity, small group work, less formal and less “bookish” methods and continuous monitoring. The system was based on the US credit system, allowing à la carte, multidisciplinary programmes of study. Vincennes was, moreover, open to those who did not graduate from high school, and the presence of a nursery and a kindergarten on its campus aimed to encourage housewives to resume their studies.

In total, this reconfiguration of French higher education led to the creation of 37 new universities and six university centres by 1970. Bordeaux tripled its count of universities, but Paris went from one to 13 as the multi-site University of Paris, whose teaching was inflexibly monodisciplinary, was broken up into smaller units.

The institutional break-up of the old universities in favour of a recomposition aimed at promoting multidisciplinarity allowed the creation of new groupings based on disciplinary, epistemological and also political affinities. The post-’68 universities were thus recomposed according to the choices of the academics themselves, offering French students a new menu of higher education choices.

As we commemorate the 50th anniversary of May 1968, French university students and teachers are once again mobilising against selective entry, leading to the occupation of several institutions. More broadly, without denying the difficulties encountered by many undergraduates, especially those doing professional and technological degrees, the protesters believe that the best solution, in the name of the democratisation of higher education and its role in educating enlightened citizens, is not greater selection in admissions but more resources to offer better academic support to such students. Some protesters are also considering a reform of secondary education.

The movement does not yet have “pedagogical committees” of a scale comparable to that of 1968, but on 5 May a first national convention of universities was held at a trade union headquarters in Paris, and 1968-style public fora on “self-managed higher education” are being planned, particularly in Nanterre, to initiate reflection on alternative reforms. The echoes of 50 years ago still resound.

Christelle Dormoy-Rajramanan is a researcher at Paris Nanterre University, associated with the National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS)’s Paris Centre for Sociological and Political Research.

Source: Getty

Source: Getty

‘The true rupture represented by May ’68 is that students quite simply stopped functioning as students and began to function as citizens’

In the summer of 1968, when the great wave of student and worker protests that had suddenly swept France retreated just as suddenly, the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre took stock. “What is important is that the action took place, at a time when everyone judged it to be unthinkable,” he concluded. “If it took place, then it can happen again.”

Sartre often got things wrong, but not this time. On the 50th anniversary of les événements de mai ’68, the unthinkable is happening again. This time, though, it is happening in the US.

Defining May ’68 is as easy as nailing a crème brûlée to the wall. Frustrated, the conservative French sociologist Raymond Aron famously dismissed it as la révolution introuvable: the elusive revolution.

But Aron could not find the revolution because there was never a revolution to be found. The events of 1968 were not a sequel to the revolutionary years of 1789, 1830, 1848 or even 1871, and its participants were less Leninist than they were Rabelaisian. The vast majority of striking students – and, more particularly, workers – did not seek to overthrow the Gaullist state. If they had, they would not have marched under banners announcing: “Workers of the world, have fun!” and “Power to the imagination”.

The true rupture represented by May ’68 is that, as New York University literary scholar Kristin Ross notes, students – including tens of thousands from high schools – quite simply stopped functioning as students. Instead, they began to function as citizens, who seized language, not power. By leaving behind their classrooms, the students created a new space for politics in a landscape dominated by the authoritarian presence of Charles de Gaulle. Their challenge was rendered iconic by the poster of an immense silhouette of de Gaulle, hand clapped over a student’s mouth, under the words: “Be young and shut up.”

This is familiar territory for the American high school students who organised and participated in the massive March for Our Lives earlier this year. Few of them have read Sartre, but it was as if they acted on his claim that existence precedes essence. Rather than remaining condemned to the intermittent mass shootings at their schools, they saw that they were – as the existentialists would put it – condemned to freedom. They too chose social action over class attendance, insisting on the freedom to redefine themselves not merely as students but as citizens, equal and free to live without the fear of bleeding to death over a calculus textbook.

The spirit of ’68 also echoes in the US’ women’s marches. The graffiti of May ’68 were provocative, but also playful. With phrases such as “Under the pavements—the beach!” and “Be realists and demand the impossible!” the protesters were not storming the Bastille. Instead, they were painting it over in wild colours, their ludic attitude posing a greater challenge than revolutionary posturing to the Gaullist state.

Consider the aims and atmospherics of the women’s marches. With many wearing the instantly recognisable “pussy hats”, marchers paraded with banners and posters whose messages – ranging from “Our rights are not up for grabs, and neither are we” to “Vaginas brought you into the world, vaginas will vote you out” – mocked those in power and made clear that women would not again submit to earlier social or political categories.

Among the abiding mysteries of May ’68 is that, bottoming out as suddenly as it billowed, it seems to have left little other than memories and monographs in its wake. The workers returned to work, the students returned to campuses and the police returned in force to reclaim the streets. Charles de Gaulle remained in power while the republic that he had created in 1958 remains standing and strong 50 years later.

And yet, the earthquake of May ’68 reshaped France’s landscape. Some changes followed quickly. For example, in 1970 the University of Paris dissolved into a dozen or so campuses. Whether this devolution marked an evolution in the quality of student life remains unclear. The result of other changes, though, could not be clearer or better. Just ask the 343 women – including celebrities such as Simone de Beauvoir and Catherine Deneuve – who, in 1971, signed a manifesto in which they declared that they all had had abortions and demanded the decriminalisation of the procedure. Three years later, the newly elected president, the young and centrist Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, named Simone Veil as his minister of health. Veil, who died last year, thus became the first woman to serve as a government minister and, in 1975, overcame furious resistance to make abortion legal.

It is, of course, impossible to truly weigh each of the factors that led to Veil’s remarkable achievement. But who can doubt that when her remains are moved, with full state honours, to the Panthéon this summer, the spirit of ’68 will also be honoured.

Robert Zaretsky is a professor in the Honors College, University of Houston.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Be realistic, demand the impossible

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?