The numbers don’t add up

We physicists are trained to live by the numbers. Error bars matter. Statistical significance matters. Reproducibility and quantitative rigour matter. And yet we still recognise that numerical precision can be profoundly deceptive. As a wild-haired icon of our field is widely, if erroneously, supposed to have cautioned, not everything that counts can be counted. And not everything that can be counted counts.

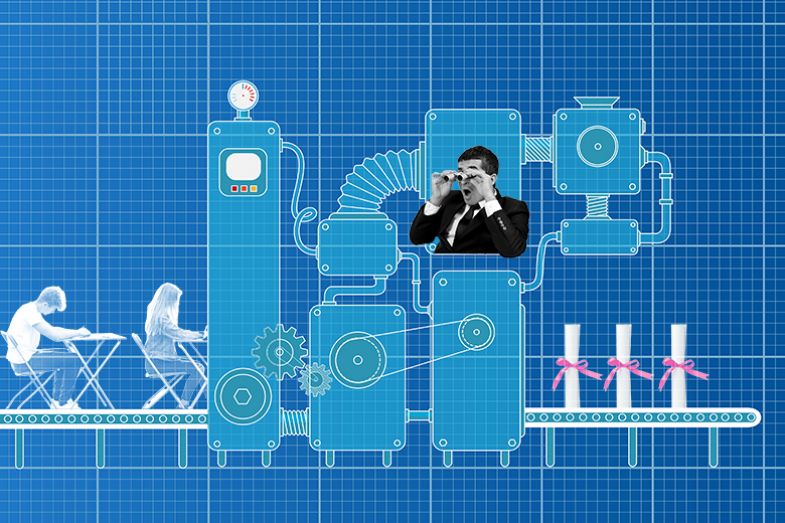

The government’s Post-16 Education and Skills White Paper flirts with the idea that a single assessment metric – something akin to the so-called Progress 8 system used in secondary schools – could be devised to hold university providers “to account” on undergraduate progression, as if such an approach could ever survive contact with the diversity of degree programmes (let alone doctoral research) across disciplines. Instead of recognising Progress 8 for the hopelessly oversimplistic measure of student outcomes relative to expectations that it is, the government instead is suggesting that cargo-cult numerology be elevated over professional judgement in higher education, too. Again.

The underlying message is wearily familiar: academics apparently can’t be trusted to do their job to the best of their ability unless kept in line by numerical targets. Judgement yields to a speciously rigorous league-table algorithm. The result? Standardised metrics that are considerably less reliable than the expertise they are designed to police.

Relatedly, the White Paper also announces that the Office for Students will assess “the merits of the sector continuing to use the external examining system for ensuring rigorous standards in assessments” – presumably with a view to replacing it with something more numerical, standardised and, therefore, “rigorous”. This would also be a huge mistake.

External examining has its flaws, but it fundamentally recognises disciplinary nuance. It accommodates complexity rather than pretending it doesn’t exist. It allows a condensed-matter physicist, a music professor, a modern languages expert and a nursing specialist to assess intellectual achievement on their own terms. It is not “one size fits all”, because higher education is not “one size fits all”.

And this is where the White Paper’s logic, such as it is, collapses under its own weight. On the one hand, it urges universities towards deeper and sharper specialism, yet, on the other, it imagines that a single, standardised, national model of “progress” could be used to compare those increasingly specialised programmes. It is impossible to simultaneously drive diversity of provision and then evaluate it as though it were homogeneous.

Universities once claimed a duty to challenge received wisdom – to speak truth to power, not to echo it. Increasingly, however, they are enthusiastically and cravenly complicit in the metrics game. They play it desperately, even when doing so corrodes the very academic rigour, intellectual honesty and educational integrity they profess to uphold. External examining – one of the few remaining practices capable of acknowledging disciplinary nuance and resisting homogenisation – risks being sidelined in the process. Metrics become mandates, strategies become box-ticking, and the incentives drift ever further from the best interests of the students that universities claim to serve.

When the metric displaces the expert, pseudo-statistics substitute for understanding. Yet the truth is that expertise – messy, contextual and heterogeneous – is what higher education actually needs.

Philip Moriarty is professor of physics at the University of Nottingham.

Revise and resubmit

In 2018, I wrote in Times Higher Education that external examining was “no longer fit for purpose”.

The problems with it were clear even in that pre-Covid era. The higher staff-student ratios that had been common at the beginning of my career 20 years earlier had permitted examiners to read all the relevant exam papers and be able to challenge individual marks. It was intense: I recall receiving large bundles through the post and dragging them up to my office for inspection, before nervously sending them back via registered delivery (luckily, they never went astray).

But universities failed to increase their resources for external examination in proportion to their expansion; they largely still pay the same paltry fee for the same few hours of externals’ time as they always did. The result is that examiners are now only sent a representative sample of exam papers. Hence, apart from dissertations, they have limited powers to amend individual marks; generally, they have to choose between changing all marks or none in a module – and, mostly, they opt for the latter.

I also remember boards of exams as being important departmental occasions that many colleagues relished. The main event was the meeting determining degree classifications, but the external examiner also had meetings with individual colleagues to discuss modules and held group discussions with the whole department over a reception or dinner. Some of the most profound and enduring advice I received on improving my own teaching and assessment came from these meetings.

To speak of them now is like talking about a different world. Today, external examiners don’t even necessarily attend the board meeting in person, never mind undertake additional chats and debates. Moreover, if there is no board discretion over awarding different degree classifications (thanks to various mathematical formulae at play), there might not be any discussion about standards at all during most meetings.

In short, while it used to be a real honour to serve a department, it has become thankless theatre.

So it might seem only natural to conclude that it’s time to pull the plug completely. This is what the Office for Students (OfS) now seems to be recommending. In its latest report, the regulator claims that “the use of external examiners is not a regulatory requirement” – and if you don’t need them, why have them? That is also the question that the recent skills White Paper tacitly raises in announcing a review of the role of external examining amid concerns about grade inflation.

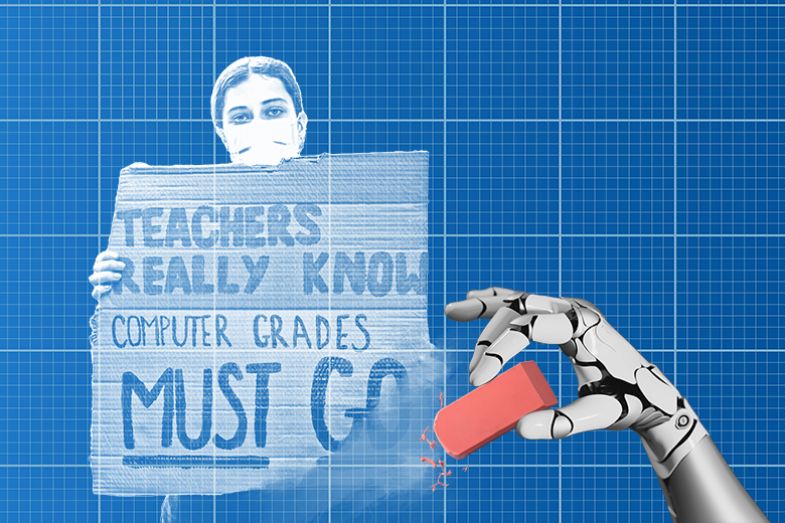

Perhaps improving the algorithms already used by universities in confirming degree classifications might indeed prove more effective than the expensive and burdensome external examining system. But I doubt it. Algorithms can get things badly wrong – recall the A-level and GCSE results fiasco in 2020.

The OfS also states concerns about grade inflation, but it is unclear to me how leaving individual providers to get on with it would improve standards or maintain meaningful comparability of awards between providers. My recommendation, then, would be to improve, not scrap, the external examining system.

Apart from the capacity issues, another major problem with it currently is that many examiners aren’t selected randomly. Typically, they are secured through personal connections and may have little knowledge or experience of how a set of assessments compares with those elsewhere. Training may be available, but they rarely access it.

The OfS should address this by creating a new College of External Examiners (CEE), to which academics apply for membership, training and mentorship. The college would serve as a pool of accredited examiners, whom it would allocate to providers solely on the basis of their expertise and availability. Full accreditation would come with status – fellowships or senior fellowships – helping to professionalise and valorise the role of examining.

Trained in how a subject discipline is taught and assessed across the sector, external examiners would also be better placed to comment on how a provider’s arrangements stack up. And they might provide independent expert advice on how local regulations relate to any grade inflation, if this is a concern.

The fees that providers currently pay directly to examiners should instead be directed via the CEE, whose regularised fee structure would ensure that similar work done is rewarded the same way at different institutions.

That would be a small price to pay for a genuinely independent system that could meaningfully improve public confidence in quality standards.

Thom Brooks is principal of Collingwood College at Durham University, where he is professor of law, ethics and government.

Showing it’s working

With the recent publication of the recent skills White Paper and an Office for Students (OfS) report on the potentially inflationary effect of changing degree algorithms, the UK higher education sector finds itself once again defending one of its most quietly effective quality assurance mechanisms: the external examiner system.

For those of us working in quality within universities and more broadly in the sector, the sigh is collective. How many times must we demonstrate the value of a system that is low-cost, deeply embedded and internationally respected?

External examiners are not just a formality. They are the independent experts who scrutinise assessment design, verify marking standards, and ensure that academic judgements are fair, transparent and consistent with national frameworks. They provide assurance, drive enhancement and help institutions respond to emerging challenges. Their work happens at the point of delivery and in real time, when it is still possible to ensure current students receive grades that accurately reflect their performance.

Cost is minimised because the external examiner system operates on reciprocity. For a typically small honorarium, between (by my rough calculation) 10,000 and 15,000 external examiners across the UK lend their expertise to one another’s institutions each year. This network is largely unseen, but its impact is profound. It’s a model of sector-wide collaboration that delivers assurance, enhancement and efficiency.

It isn’t perfect. Occasionally, external examiners miss mistakes or are not critical enough. Sometimes institutions fail to follow sector guidance designed to ensure the independence of external examiners. As with everything we do, there are always enhancements to be made. But the system’s overall effectiveness is not open to question.

Following the Quality Assurance Agency’s guidance, all the programmes at my institution, including all their component modules, are scrutinised by an external examiner. That person does much more than oversee the marking of assignments: they also contribute to internal cyclical programme reviews, programme validation, curriculum structure and assessment design. They meet with our students and staff to discuss how teaching could be improved. Their reports inform institutional actions, drive enhancement and help us share good practice.

This isn’t just a tick-box exercise: it’s a reassurance to students, staff and the public that our degrees are credible and our standards robust. In my institution alone, we analyse and respond annually to about 150 external examiner reports from 130 external examiners.

The OfS seems to suggest that even this level of scrutiny is ineffective. But what would replace it? A centrally-imposed compliance model? A checklist of “do not or else”s? Any verifiable alternative would likely cost significantly more or deliver far less.

In Scotland, we’ve have had our first year of the new Tertiary Quality Enhancement Framework, meeting European standards and guidelines. It was built through extensive consultation with universities, colleges, students and professional bodies, and it requires externality in the form of external examiners as a key component, providing impartial confirmation that academic standards are appropriate and aligned with sector-agreed benchmarks.

Higher education curricula are shaped and informed by the latest disciplinary research. Hence, only peers working at the forefront of these fields are qualified to evaluate what we teach and how we assess. External examiners actively help us adapt to change, whether it’s the rise of AI, the impact of industrial action, or the legacy of the Covid pandemic.

The recent reopening of the debate on external examining flies in the face of the 2022 sector-wide review, which, after consulting widely, developed a set of principles for effective external examining that “reiterate the value of appointing external examiners…providing confidence for students and the public that the degrees being awarded are a reliable and consistent reflection of graduate attainment”.

It also risks fragmenting the UK’s quality frameworks even further, weakening the sector’s ability to self-regulate and undermining the international reputation of UK higher education.

In these times of significant pressure, the last thing we need is to dismantle an efficient and effective system and replace it with a retrospective compliance model that lacks nuance, expertise and sector trust and ownership. Instead, we should reaffirm our commitment to peer-led quality assurance – and work to improve it where needed.

Clare Peddie is vice-principal education (proctor) at the University of St Andrews and deputy chair of the Quality Council for UK Higher Education.

The absolute minimum

In its recent White Paper on post-16 education, the UK government expresses its concern about grade inflation, which it interprets as a lowering of standards. As part of that, the document announces a review of the role of external examiners, implying that the inflation may be a result of their failure to do their jobs properly.

Specifically, the government intends to assess “the merits of the sector continuing to use the external examining system for ensuring rigorous standards in assessments” and “the extent to which recent patterns of improving grades can be explained by an erosion of standards, rather than improved teaching or assessment practices”.

Grade inflation is real: from 2011 to 2018, the percentage of UK students awarded a first-class degree almost doubled from 15.7 per cent to 29.3 per cent. However, it is absurd to blame that on slacking external examiners. The most likely reasons are actually the government’s own measures aimed at improving teaching and learning.

Broadly, quality assurance schemes reward departments that produce lots of firsts and 2:1s and, crucially, those that do not fail their students. That has always seemed to me to penalise the maintenance of standards since, in my experience, many students who fail do so not through poor teaching but because they do not do enough work.

Another inflationary pressure is the use of the National Student Survey (NSS) as a measure of teaching quality: nothing pleases students more than their own apparent success. In reality, genuine improvement in learning is best achieved by introducing more student-led activity, but many students do not like that challenge, and their dissatisfaction can be reflected in their NSS responses.

Another cause of grade inflation is universities’ efforts to be proactive in supporting students with health and other issues by relaxing the rules around resit eligibility. This is laudable – but allowing more attempts inevitably improves outcomes.

In reality, external examiners are just one cog in the machinery of quality assurance. Their main duty has been to act as a critical friend to a department and to ensure that the academics providing the programme(s) do so correctly within their particular quality framework and that they treat their students fairly. The examiners have neither the time nor the capacity to impose a universal standard.

More to the point, there is no such thing! That is to say, universal assessments across all universities would be as undesirable as they would be unworkable – not least because they would destroy the sector diversity that the White Paper sees as positive and encourages more of.

In practice, degree programmes aim to achieve specific outcomes for specific cohorts. That should be the starting point for any re-evaluation of the system. Students who attend Oxford Brookes University will have a quite different profile from those who attend the other university in the city and, in general, they will pursue different courses, with different career outcomes. Neither is better or worse – what criteria would we use to decide? – they are just different.

Does that mean we have to abandon the notion of standards and quality assurance? Absolutely not! But we must measure programmes in terms of what they are trying to do. Each programme should have a statement that outlines the type of students the course is designed for, the methods and variety of the teaching, and the expected graduate outcomes (stated as quantitatively as possible). Making that statement prominently available to prospective students would minimise the obvious risk that universities would set artificially low targets: students would not choose a course with poor expected outcomes.

It might help to abolish the dated classification of degrees into firsts, 2:1s etc, which implies some sort of equivalence in terms of standards. But that is a separate question.

In any case, the role of external examiners would not change significantly in this system. They would continue to offer a department an independent, external, respected view from within the same subject community on issues such as the fairness of assessment. And while an absolute standard for degree classifications is unattainable even within a given subject area (I have no idea what a comparison of standards between subjects might mean), it should be possible – necessary, even – to define and police a minimum standard.

In subjects such as medicine, engineering and some of the sciences, there are external accrediting bodies that do just that. There is no reason why other similar bodies, possibly in collaboration with the Quality Assurance Agency, should not develop criteria to define minimum standards in their areas.

These would be tools for external examiners to use in evaluating a programme, alongside continuing to guarantee that the department is doing what it says it is doing. If a programme claimed that 50 per cent of its graduates became business leaders but, in reality, 90 per cent ended up in casual jobs, external examiners would call that out.

Ensuring minimum standards even more rigorously even while explicitly casting off the illusion of equivalence across the board would allow external examiners to play a vital role in a more enlightened system of degree programme assessment – while preserving the diversity of provision that is one of the positive features of UK higher education.

Peter Main is professor emeritus in the department of physics at King’s College London. His ebook, Assessment in University Physics Education, is available from IOP Publishing.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?