So Jo Johnson is gone, brought down by poor judgement demonstrated by, first, the appointment of Toby Young to the board of the Office for Students, and second by his obstinacy in defending that decision to the bitter end.

The day before his departure he was arguing that Young had been unfairly represented by a “one-sided caricature from armchair critics”, ignoring the numerous indicators of Young’s unsuitability for a role that required wisdom rather than impulsiveness and polemic.

As is customary on these occasions, Johnson’s tone in defeat was positive; he tweeted: “Farewell unis and science – our greatest national asset & best thing about this country.” But this was the first time I’ve seen him praise the sector without immediately following up with an onslaught of criticism.

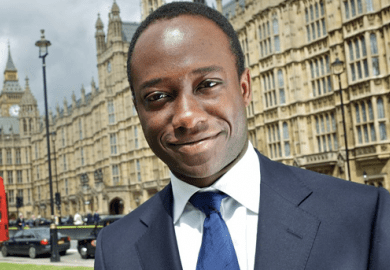

Farewell unis and science - our greatest national asset & best thing about this country. It's been an honour to have had this role - proud of all our reforms, especially the Teaching Excellence Framework & the Higher Education & Research Act. Brilliant successor in @SamGyimah

— Jo Johnson (@JoJohnsonUK) January 9, 2018

While in office, he accused those working in universities of not providing “value for money” for students, of neglecting teaching because they prefer to do research, of suppressing free speech, and of acting to block anyone who wants to enter the higher education sector because of fear of competition. Any attempt to rebut these criticisms was dismissed as complacency, self-interest and resistance to change.

His principal goals have been to ensure that students get better “value for money” and to help “alternative providers” to enter the sector to improve competition. If we’re talking about caricatures, then Johnson’s view of higher education is a good example. He regarded the higher education sector as a market, where universities make money by selling degrees, and students are consumers who buy a product that will allow them to earn money.

In this model, the interests of universities and students are in conflict. Johnson did not appear to grasp that, although this model applies to some for-profit providers, it does not represent the reality of our existing universities. Universities need money to operate, but it is not the purpose of their existence: their goals are to educate people to be thoughtful, knowledgeable citizens who can evaluate evidence and arguments.

Impervious to evidence

Given his Conservative credentials, it’s not surprising that Johnson’s reforms have been criticised by those on the left wing of politics, but the problems went well beyond party political lines. Johnson was characterised by a remarkable level of obstinacy and imperviousness to evidence. Critics of his Higher Education and Research Bill were not just left-wing firebrands, but also a large swathe of those in the House of Lords, who expressed well-articulated concerns about the impact of changes to the governance of higher education. They noted the real risks associated with encouraging for-profit providers into the sector – of course, it is possible to have private universities that are of high calibre, but there is little sign that the “alternative providers” that are waiting in the wings are going to rival Harvard or Yale.

I have blogged previously about Johnson’s other main achievement, the teaching excellence framework, noting its weak foundations and statistical limitations – limitations that have been emphasised by the Royal Statistical Society and the Office for National Statistics.

The potential for damaging our universities by badging them according to a TEF that does not measure teaching excellence was stressed time and time again – and yet Johnson persisted. Last year at the annual general meeting of the Council for the Defence of British Universities, Martin Wolf gave a highly critical speech about changes to higher education. As discussant, I raised the question of why Johnson was pressing ahead with reforms when so many knowledgeable people were warning of the possibility of real damage to the sector. It was hard to believe that he wanted to destroy our world-class universities, but he seemed quite impervious to argument. Some of those in the room had tried to talk to Johnson about their concerns, but said that he was extraordinarily obstinate.

I’m under no illusions that Johnson’s successor, Sam Gyimah, will overturn his reforms. All the indications are that he is a hard-line Tory, which is to be expected given that he is a Conservative appointment. But I do hope that he will at least show some flexibility in how he works with the sector and will listen to evidence and arguments before rushing in to implement change. Johnson’s approach was recently described as “confrontational” by Alistair Jarvis, the chief executive of Universities UK, who noted: “The student interest is framed narrowly, often in opposition to institutional interests, rather than reflecting the complex and multifaceted dimensions of students’ relationships with their higher education provider, not least as participants in institutional governance and decision-making.”

Johnson always appeared to treat consultation exercises as necessary evils, rather than an opportunity to solicit views. Universities are already struggling with the fallout from Brexit: we could be badly damaged if changes are introduced impulsively without regard for consequences. The sector is indeed one of the UK’s greatest assets: let’s hope that the new minister will recognise this and work with academics to shore up this success, rather than treating them as the enemy.

Dorothy Bishop is professor of developmental neuropsychology at the University of Oxford. This post originally appeared on the CDBU blog.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?