Bitter feuds and heated rows have long been part of departmental life within universities. Personalities and egos clash, research agendas conflict and academic clans fight their corner, generating a friction that some regard as essential to healthy scholarly environments. Famously, Francis Crick’s boss at the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge, Lawrence Bragg, fumed at the incessant loud talking and brash manner of the future Nobelist; all was forgiven when Crick discovered, with James Watson, the structure of DNA in February 1953.

But has discord tipped over into downright hostility between colleagues, rendering working relations dysfunctional? Figures obtained by Times Higher Education under the Freedom of Information Act show that the use of grievance procedures has rocketed at several leading UK universities in recent years.

At the University of Manchester, for instance, 47 people lodged formal grievances in 2024-25. This is still a low number in an institution that had nearly 11,000 FTE staff in 2023-24, but it is a 260 per cent rise on the 13 lodged in 2018-19. Meanwhile, 36 people submitted grievances at the University of Edinburgh last year, compared with only eight in 2018-19 (a 350 per cent increase).

At UCL, some 56 formal grievances were submitted in 2024-25, compared with only seven in 2018-19, representing an eightfold rise, while nearby King’s College London saw 59 formal grievances from staff members last year, against 12 in 2020-21 (the earliest available year for data) – a fourfold rise. Imperial College London’s grievance numbers hit 55 in 2023-24, up from 23 in 2020-21.

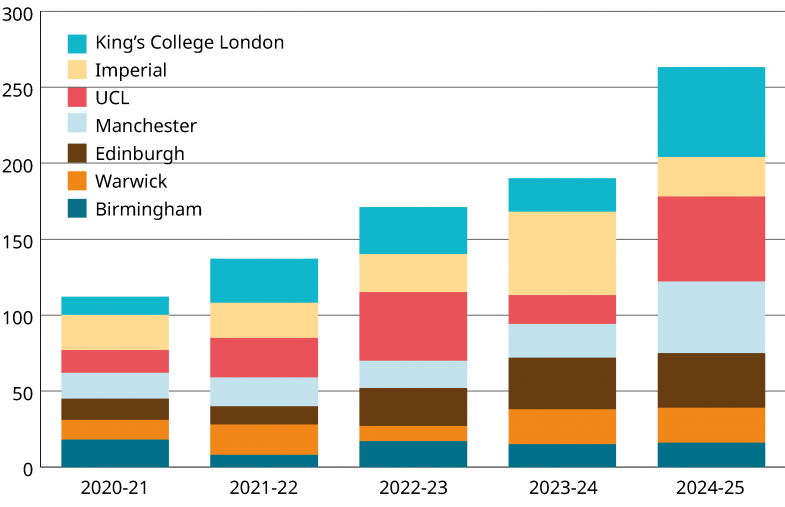

Numbers at the universities of Birmingham and Warwick were more stable, with the former’s grievance count actually falling from 19 in 2018-19 to 16 in 2024-25, while Warwick’s rose from 18 to 23 over the same period. However, overall, staff grievances rose by 174 per cent for the five universities (also including Edinburgh, Manchester and UCL) that provided data for all of those years. For all seven universities surveyed, submitted grievances rose from 112 in 2020-21 (the first year for which all provided data) to 263 in 2024-25, a 135 per cent increase over that shorter period.

Formal grievances lodged at seven major UK universities

So what might explain these rising grievance caseloads, and how are they affecting university life? Andrew Oswald, professor of economics and behavioural science at the University of Warwick, believes that the sector’s dire financial situation, which led to 13,000 job losses last year alone, is exerting a powerful effect. “Stress leads to greater human conflict and there is a great deal more stress in UK universities these days,” said Oswald, whose research has focused on human well-being and the workplace. “I’ve seen the same thing happen in other declining industries throughout my lifetime; workloads go up, morale falls and job satisfaction decreases. People in higher education are miserable and under pressure, which can lead to shorter fuses.”

Equally, in the “current climate” within UK academia, it is “logical” to complain, Oswald believes: “Some grievances will be an attempt at self-protection; taking the legal route makes it expensive and difficult to get rid of you.”

But the job losses are not the only factor fuelling the grievance caseload, observers suggest. And not all of the factors are negative. Female university staff may feel emboldened to report sexual harassment in the post-#MeToo era, for instance, while university training and tools to encourage the reporting of misconduct, including microaggressions, may have pushed up complaints. Polarisation on campus regarding the conflict in Gaza and free speech issues might also explain a more fractious recent climate.

But some believe a bigger cultural shift is also exerting an influence, noting that staff are increasingly likely to lodge formal grievance complaints in the first instance, rather than seek to settle relatively minor disputes informally via a line manager – or even directly with those committing the offence.

“Some of the grievance complaints I’ve seen are ridiculous,” explained one University and College Union case manager at a Russell Group university. “In some cases, people have misinterpreted innocuous comments and escalated them into a full-blown complaint. Misunderstandings that might have been cleared up with a conversation result in investigations lasting months,” she explained.

Another union representative said he had seen many more formal grievance complaints related to interpersonal disputes that might have previously been settled through informal chats with a department head.

“Previously, people might have been encouraged to make an informal complaint first and resolve it at that stage. A formal complaint would only be encouraged if it was a very serious offence or the behaviour was persistent, which would lead to an investigation,” the representative said.

Another factor in the rise of complaints, particularly among professional staff, may be the rise of remote and hybrid working. Some managers told THE that this has gravely undermined the cohesion of teams, whose members may seldom meet in person outside occasional meetings. “I’m frankly fed up of mediating petty arguments that researchers should sort out themselves,” one manager commented.

For Oswald, the increased use of official complaints channels probably reflects the higher proportion of professional service staff working within UK universities compared with a decade ago.

“Most academics have no idea about how to bring a grievance, but professional service staff are much more schooled in these matters,” he said. “When I was a young academic, a senior professor used to shout at me regularly at the top of his voice – it never occurred to me to report him. I just thought he was a prat and got on with my research. But I don’t think non-academics would ever put up with that kind of treatment.”

Frank Furedi, emeritus professor of sociology at the University of Kent, believes that HR departments have expanded the definition of bullying to such an extent that even academics are inclined to perceive it much more frequently than they once did.

“Bullying now refers to anything that is mildly unpleasant for an individual – it has become an all-pervasive threat that people see at every turn,” Furedi said. “The idea of bullying encourages students and staff to see themselves as vulnerable, almost like children – it infantilises us and goes against the critical spirit of the academic vocation, which is challenging ideas and asking people to explain themselves,” he said.

Whatever the cause, the increased rise in grievance procedures comes at a financial cost. According to a 2021 study by University of Westminster academics Richard Saundry and Peter Urwin, a formal grievance costs UK employers an average of almost £6,500 per employee to handle, including not only the time of line managers, human resources and legal staff but also losses related to sickness absence, presenteeism and other knock-on effects on productivity.

If those indicative costs were applied to the seven universities about which Times Higher Education gained information, the cumulative total of the 263 grievances lodged in 2024-25 would be about £2.4 million. Across the UK’s 150 or so higher education institutions, the bill likely runs into tens of millions of pounds.

Moreover, if a grievance leads to an employee exiting the organisation, the cost – including lost output and replacement – rises to up to £45,000 if they feel the complaint was mishandled and they claim constructive dismissal, according to the study, which was commissioned by the mediation service Acas. With the several layers of management and opportunities to appeal in universities, plus the sector’s relatively high salaries, those costs are likely to run much higher than those averages.

Then there are the legal costs incurred by staff themselves. In one case, whose details Times Higher Education cannot divulge for confidentiality reasons, a senior UK medical researcher was suspended for more than a year and spent more than £150,000 fighting allegations of improper conduct before an investigation dismissed all charges. “It’s hard to overstate how badly this person’s career was damaged by this grievance; he had job offers rescinded and couldn’t apply for grants while the investigation continued,” explained a colleague.

There are also considerable psychological costs to grievance procedures, particularly for those accused. Of course, all allegations of serious misconduct should be investigated. And those costs could also be rising due to a dynamic that one union official is increasingly seeing, whereby managers pick up on certain cases that are “more like a personal dispute” and “immediately turn them into [formal] disciplinary cases”, becoming “invested in one side” of the argument. “Even if the person is not [ultimately] disciplined, relationships are damaged badly,” the official said.

Some of those who have been on the end of formal investigations for their part in departmental spats and squabbles regard themselves as having been targeted because managers regard them as bothersome and see the complaint as a way to get rid of them.

Information on how complaints are resolved is thin on the ground, with few universities apparently collecting comprehensive data on it and only two providing it to THE. Yet the proportion of complaints that lead to formal censure may be relatively low. Of Manchester’s 47 formal grievances in 2024-25, only 10 led to investigations and only one led to any disciplinary action (2 per cent). In 2023-24, 22 complaints led to 10 investigations and one case of disciplinary action (5 per cent).

At Edinburgh, the conversion of complaints into formal censure is somewhat higher, however. In 2024-25, 36 grievance complaints led to 19 investigations and seven disciplinary actions (19 per cent), while the figures for 2023-24 were 34, 28 and 11 (32 per cent), respectively.

Either way, those who have been subject to investigations that ultimately go nowhere insist that the conversion statistics are only part of the story. With investigations taking upwards of a year, the “process is the punishment”, claimed one senior scientist, who was subject to a grievance complaint that was completely thrown out after an investigation lasting months.

“Some of the grievances I’ve seen are massively disingenuous. They’ve been made by [junior] researchers who have been told their work isn’t up to scratch or whose contract won’t be renewed. They have nothing to lose because there is no real censure if you make a trivial complaint, despite what the procedures claim,” he said.

“There are…clear timelines for these investigations to be completed, but these aren’t adhered to and there is no reason for HR to expedite matters. While suspensions and investigations run, an academic’s career usually goes into freefall and it’s very hard to recover even if none of the complaint is upheld,” he added.

Like Furedi, the senior scientist is sceptical of the role of HR in complaint handling, claiming that HR departments are “an extension of university management – they are not representative of the academic community, and nor do they have a legal background. They represent enforcement.” And while HR departments sometimes bring in external advisers to help resolve cases, these people “rarely have any academic experience, and, more importantly, they are not neutral: if they’re commissioned by HR then it’s in their interests to accede to HR’s agenda and uphold at least some of the case. Otherwise, they will not be employed again,” the scientist said. “They don’t want to make HR look foolish by throwing out the complaint in its entirety.”

Those overseeing investigations, fraught with emotion and contested versions of events, deny that the system is rigged in any particular direction or that delays are being purposefully used to make life difficult for any parties.

“Handling grievances can be a time-consuming and complex process and nobody wants it to drag on any longer than necessary,” explained Helen Scott, executive director of Universities Human Resources (UHR).

“However, if matters are to be properly investigated and aired, then it may take a long time if there are multiple grievances, several people involved, or matters are complex and require deeper investigation. Universities will always want to achieve a fair outcome for everyone concerned, but this may mean that it takes longer than some parties wish: for example, when someone is off sick, trade union representatives are unavailable, or legal advice is required.”

Nevertheless, resolution policies that advocate for early dispute-resolution steps to be taken before formal grievance complaints are launched “may help to achieve an informal and quicker resolution that’s better and longer-lasting for everyone”, added Scott.

But the senior scientist believes that matters need to be taken out of HR’s hands entirely. In his view, “a truly independent body staffed by employment lawyers employed on a retainer would be both fairer and cheaper...These lawyers could represent several universities…and could take decisions quickly about whether these grievances have any merit,” he said.

“We need a system that isn’t driven by HR. The current system is entirely flawed and it is destroying people’s careers. People are forced to wait months before cases are thrown out as baseless – it takes a huge toll on your mental well-being, and it’s expensive for all parties.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?