Already struggling to address its historical debt to enslaved black Americans, US higher education is now beginning to confront one of its central origin stories: a massive theft from indigenous populations.

That recognition began growing over the past year, after an extensive analysis showed that 52 US universities – largely major public institutions – were built on land directly taken from Native Americans.

That land, presented and long understood as gifts from federal holdings, has an estimated current value of nearly $500 million (£360 million), according to the investigation led by a Native American journalist and a University of Cambridge history lecturer.

Even Native American tribes were unaware of the foundational role of indigenous land seizures in the long-revered Morrill Land-Grant Act of 1862, and are still trying to sort out the implications.

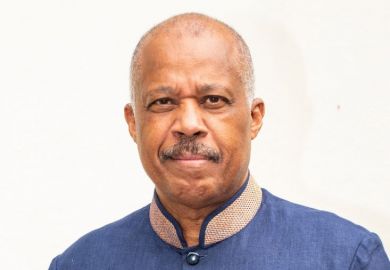

“This is blowing everybody’s mind,” said John Low, associate professor of comparative studies at Ohio State University and a citizen of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians.

In the year since the discovery by the investigative team headed by Tristan Ahtone of the Kiowa tribe and Robert Lee of Cambridge, most US universities have been slow to respond, said Stephen Gavazzi, a professor of human development and family science working with Dr Low and other Ohio State colleagues to guide their university’s response.

Many institutions have issued statements acknowledging the reality of native land theft, Professor Gavazzi said. But Ohio State, he said, is among only about five that have begun the work of contacting all the affected tribes – Ohio State alone has land taken from 108 of them – to hear their thoughts on what should happen.

“A lot of what is happening right now is catching people up on the historical significance of what happened,” Professor Gavazzi said.

The revelations come less than a decade after Georgetown University admitting raising money by selling 272 enslaved people in 1838, pushing dozens more universities in the US and beyond to look harder at their own slavery-related profits and the accumulated debts they entail.

In both instances, experts said, university administrators and trustees have been slow to respond, typically forced to act only by the demands of students, faculty and outside activists.

“US higher education has been an utter failure in rectifying this grave, historic and profitable injustice,” Davarian Baldwin, professor of American studies at Connecticut’s Trinity College, said of the stolen indigenous land.

The revelations stand as especially jarring for US institutions given the heroic stature of the Morrill Act, signed into law by Abraham Lincoln, which gave institutions native lands they could either use directly or sell to raise revenue. Its beneficiaries included Cornell University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, although the act mainly funded flagship public institutions with an aim of democratising the availability of higher education.

Their main membership group, the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities, has long celebrated Morrill as their moment of altruistic birth. Shortly after the Ahtone-Lee report, deriding the 52 beneficiaries as “Land-Grab Universities”, the APLU added to its website a “statement of land acknowledgment” that includes a general promise to better serve Native American students and their communities.

The APLU said it has partnered with member institutions to support indigenous students, and planned to convene a meeting next month of indigenous leaders from across North America to consider additional steps.

Dr Low said he agreed that asking Native American leaders for their ideas was the most important initial step. Those already taking that step, beyond Ohio State, he said, included MIT, Cornell and the University of Connecticut.

The most advanced efforts involve South Dakota State University, which began its Wokini Initiative in 2017, well ahead of the Ahtone-Lee revelations. Its outreach includes scholarships for indigenous students and expanded Native American educational programmes.

A major challenge for other universities involved finding tribal representatives, Professor Gavazzi said. He said that his team, stymied by the pandemic and the limited resources of native populations, has been able reach only 12 of the 108 tribes whose land funded Ohio State.

From those dozen, Dr Low said, ideas for redress beyond scholarships and returning land outright include hiring more indigenous faculty, creating on-campus community centres for indigenous students, and expanding humanities-oriented Native American curricula to provide more science and engineering options.

Massive amounts of student aid and community services should be seen as just a start, Professor Baldwin said. “The bottom line must be: land back,” he said.

Professor Gavazzi said he understood the importance of land restoration. But he also urged talk at this early stage to be tempered by reality.

“If we’re going to start something, we had better finish it,” he said. “Because these tribal nations have heard this before – they’ve been sold lots of bills of empty promises and broken treaties – so we have to be very careful in what we’re doing here, and make sure that we under-promise and over-perform.”

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: US universities struggle to repay Native American debt

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?