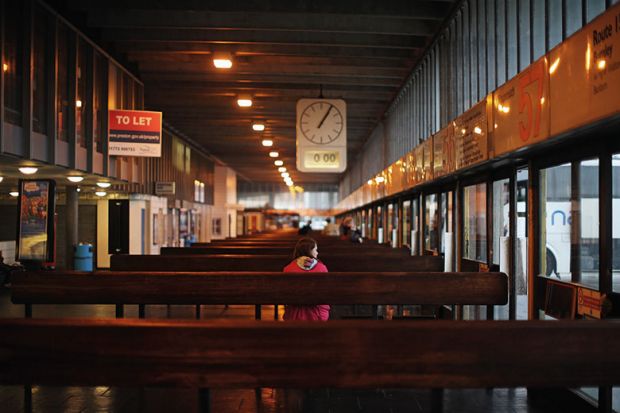

The outsider’s clichéd view of Preston, Lancashire would not stretch far beyond Tom Finney, post-industrial decline and its infamous bus station, which divides opinion between those who see a treasure of the brutalist style or one of the world’s ugliest buildings.

But now the University of Central Lancashire is one of seven anchor institutions in the town, led by Preston City Council, that have created the “Preston Model” – and put that system at the centre of the UK Labour Party’s vision for a new kind of economy. The concept has drawn admiring coverage in some quarters of the national media and Labour figures such as shadow chancellor John McDonnell and former leader Ed Miliband up to Uclan.

There are two elements to the Preston Model: the anchor institutions investing as much as possible of their procurement spending with local firms instead of national or multinational companies; and encouraging the growth of worker-owned cooperatives to fill gaps in the local supply chain. In the Labour-run city council’s description, the Preston Model is about “local people taking back control” (reinterpreting the Vote Leave campaign’s highly effective “take back control” tag line, a slogan now even more divisive than Preston bus station).

Uclan has transformed its approach since it lost millions of pounds on overseas branch campus ventures and attempted to become a private company under previous leadership. Julian Manley, the Uclan social innovation manager who has been a key figure in the development of the Preston Model, said that its new example could be followed by other universities. “People look at this and say, ‘this is how the university and the town can get together to make a genuine difference’.”

With some Conservative MPs fighting open warfare against Theresa May over Brexit, the possibility of a Labour government taking power is less improbable than it once seemed to many. The party’s pledge to abolish tuition fees has drawn huge attention. But beyond that, what might a Labour government mean for universities? The party has significant connections with new thinking that puts universities at the heart of reinvigorating local economies and civic life beyond the major cities.

The Centre for Towns thinktank was launched last year by Ian Warren, a data analyst; Lisa Nandy, the Labour MP for Wigan; and Will Jennings, professor of political science and public policy at the University of Southampton. It has since conducted research into the economies, demographics and electoral importance of towns.

Ms Nandy said that the creation of the thinktank was prompted by “several warnings from the public that all is not well in our towns” over the past decade, notably rising support for Ukip prior to 2016 and then the UK’s vote to leave the European Union.

Ms Nandy sees the draining of the working age population from towns to cities, in the wake of the loss of industry and manufacturing jobs, as driving several pressing national policy problems. The loneliness of older people whose children and grandchildren are forced to live hundreds of miles away, “the decline of our high streets” and “the collapse of our bus services” are among the issues that she cited.

Ms Nandy said of potential solutions in the towns agenda: “Universities are absolutely crucial to all of this.”

University towns have “hung on to their young people and been able to create a really vibrant economy off the back of it”, keeping far more of their pubs, banks and bus networks than other types of town, she said.

Twenty MPs attended the Centre for Towns launch event, mostly Labour but some Conservative, added Ms Nandy. “Every single one of them was asking for a university in their town because they see that as the key to success,” she continued.

But it is clearly not possible for every town to have a university. So how can the benefits of universities be spread to more towns?

“One of the key points about that is about universities doing outreach, thinking much wider in terms of their responsibilities,” said Ms Nandy. “In Manchester, the responsibility [of the universities in the city] isn’t just to the people of Manchester but actually to the people of Greater Manchester. What are they [the universities] doing to reach out to people in places like Bolton, Wigan and Oldham to make sure we help to close the skills gap there?”

When it comes to attracting more businesses to towns and giving young people the decent jobs that would allow them the choice of staying, increasing skill levels in towns is crucial, Ms Nandy argued. And lifelong learning is “particularly important when you think about trying to create new industry in those areas”, she said.

Towns are also seen by many as the major electoral battleground of the next election, whenever that may come. While there was a big swing nationally from the Conservatives to Labour at the 2017 general election, the Tories successfully prised six town seats away from Jeremy Corbyn’s party. Hence Labour’s recent “Our Town” party political broadcast, aired on the evening after Mr Corbyn’s party conference speech.

The agenda put forward by Ms Nandy and the Centre for Towns could chime with Labour’s plans for a National Education Service, said Gordon Marsden, the party’s shadow minister for further education, higher education and skills. The NES includes the pledge for free, publicly funded higher education – which many, including some within the party, have criticised as a “middle-class giveaway”. But there is also a commitment to abolishing further education fees.

While not every town can have a university, many have further education colleges, and one in 10 students studying a higher education course does so at a further education college.

Mr Marsden often emphasises the NES as a vision for “lifelong learning” and breaking down the barriers between further and higher education. That could bring not just increased social mobility, he argued, but “an evening out of economic activity” across the country “as one of the potential benefits of the NES”.

Giving Preston a greater share of the economic activity stimulated by its anchor institutions is the aim for Uclan in its involvement with the Preston Model.

The same year that it began, in 2013, Uclan’s previous vice-chancellor, Malcolm McVicar, departed.

“A few years ago, this university was attempting to go global and have a university abroad,” said Dr Manley. “Since then, we have a new vice-chancellor, Mike Thomas, who has shifted the focus of the university to being a more caring, more compassionate member of the Preston community as well.”

The Preston Model was set in motion after Dr Manley, who took up a full-time role leading Uclan’s involvement with the scheme this month, organised a symposium at Uclan in 2013, based around a talk by a representative of Mondragon, the Basque federation of worker-owned cooperatives which includes the cooperative Mondragon University.

Dr Manley, who had worked with Mondragon when he ran a consultancy and training organisation, met local councillor Matthew Brown, now leader of Preston City Council, at the symposium.

At the time, the council was preparing an economic strategy and Mr Brown was interested in cooperatives.

Since then, Dr Manley has been “working in partnership with Matthew on a personal level” and the university has been “working in partnership with the council on an institutional level”.

Uclan’s procurement analysis focuses on its top 300 providers of goods and services by value. Over the course of the three years to the financial year ending in July 2017, it increased the proportion of this money spent with Preston suppliers from 8 per cent to 21 per cent. In 2016-17, that amounted to £63 million spent with those Preston suppliers.

But for some goods and services, there are no local suppliers. Filling these gaps is part of the aim of Uclan’s support for undergraduates and graduates to work in, and own, cooperatives. This also provides employment opportunities for students “in an ethical way”, said Dr Manley, while also giving alumni more opportunity to remain in Preston instead of leaving for London or Manchester after graduation.

Dr Manley said that Uclan was supporting a digital media cooperative, which will eventually consist of third-year undergraduates and graduates as members. The university has also used its business hub, Propeller, to provide space for cooperatives.

In addition, Uclan has supported social enterprise The Larder, a healthy cafe, cooking academy and catering service run by a PhD student, said Dr Manley.

If the university spends with local firms and cooperatives, wealth is generated for people in Preston, he argued, “as opposed to shareholders who have nothing to do with Preston – they may be in some tax haven somewhere, who knows”.

Given that the reality of existence for English universities under current policy is competition with each other to attract students, competition to perform in the teaching excellence framework and competition for research funding via the research excellence framework, some in higher education may see the idea of growing the civic role of universities as nice, but essentially marginal.

Those major research-intensive universities that see themselves in competition with global rivals may, in particular, find little to attract them in such ideas. But while it is true that post-92 universities are often, by nature of their histories, more closely linked to their towns and cities, some Russell Group members, notably the University of Sheffield, are also prioritising those connections now.

The ideas here may have Labour links. But regardless of hypothetical electoral outcomes, the scale of economic challenges facing the UK’s towns and the urgent need to find a functioning post-Brexit economic model for the nation may require fresh approaches to the civic role of universities.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Universities to ‘lead revival of towns’

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?