Are postgraduate researchers “doctoral students” or “doctoral candidates”? The difference might seem trivial, but it does matter, insisted Giulia Malaguarnera, president of the European Council of Doctoral Candidates and Junior Researchers (Eurodoc).

“Doctoral candidates are, for us, all researchers enrolled in a PhD – naming them ‘students’ is a serious problem,” said Dr Malaguarnera, who believes this categorisation is unhelpful because it downplays the enormous range of professional tasks undertaken during a doctorate.

“Considering the PhD as a study programme makes it seem that the PhD holders have no working experience, which is crazy after the amount of hours that they spend working,” she said. The recognition of PhD candidates as professional “employees” – a key objective of Eurodoc, which has been achieved in many European states – will “reduce researchers’ precarity and improve their employability in and out of academia”, insisted Dr Malaguarnera.

This long-standing debate has also been revived this month in the UK with the launch of the University and College Union’s “postgraduate researchers as staff” manifesto, calling for PGRs to be given terms and conditions “comparable” to those of employees and for an end to any requirement to deliver unpaid teaching as part of a scholarship, bursary or stipend.

The campaign’s objectives might seem uncontroversial – the European Commission stated that PGRs should be treated as “professionals” as far back as 2005 – but the early days of the pandemic, which saw PGRs quickly lose paid teaching duties amid budget cuts, has highlighted the need for reform, said the union.

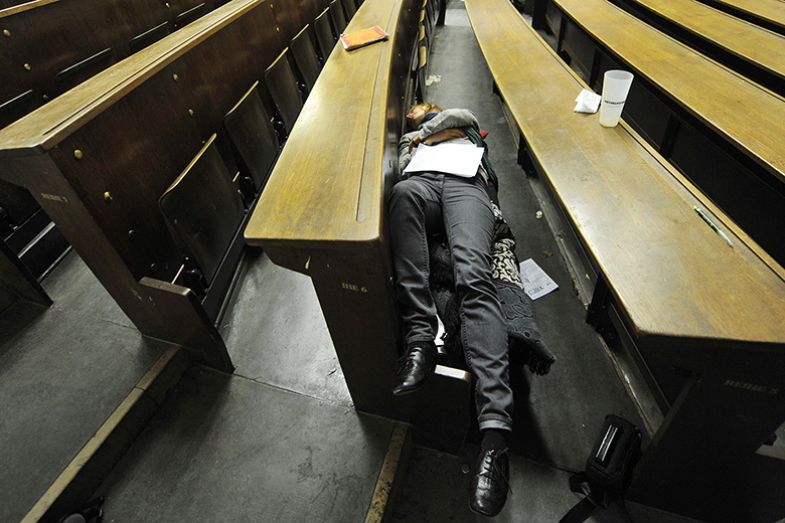

Even before Covid, serious problems of precarity-related stress were evident, Alex Kirby-Reynolds, a postgraduate researcher in the University of Sheffield’s department of sociological studies, told Times Higher Education.

“I think funders and universities recognise that there is a lot of dissatisfaction with the current system, with mental health problems being endemic, and are keen to explore ways in which this might be addressed,” said Mr Kirby-Reynolds, who hoped to see the campaign spark a “conversation within the UK higher education sector between PGRs and key stakeholders around how we can move towards a system where the former have greater security”.

The growing number of self-funded PhD students – only 22,000 of the UK’s 110,000 doctoral candidates are funded by research councils – who often rely, to varying levels, on teaching to maintain their studies, was a big reason why reform is needed, he added.

“Much of our campaign is geared towards improving the situation for self-funded PGRs, where we see it as exploitative that they are required to pay fees in order to conduct qualitatively similar work as lecturers, early career researchers and other PGRs,” said Mr Kirby-Reynolds. Observing that “many feel forced to undertake unpaid work in order to be competitive in the job market”, he added that he hoped the change in status would “offer some protections there through formalisation and proper workload allocation models that more senior staff have”.

The campaign, he explained, was keen to explore the Danish, Swedish, Norwegian and Dutch models, where PhD candidates are formally recognised as staff and, in some cases, paid salaries not dissimilar to those with PhDs: in the Netherlands, for instance, “employee PhD candidates” are paid €30,990 (£26,620) in their first year, rising to €38,982, more than double the £15,609 minimum stipend awarded by UK research councils, while also receiving holiday allocations worth 8 per cent of salary. In Norway, doctoral candidates receive a wage equivalent to €45,304 for a stipulated 37.5-hour working week.

But some UK doctoral supervisors are worried that treating doctoral candidates as staff might encourage them to take on more paid teaching when they should be focused on their studies.

“The problem is PhD students get hooked on teaching – it should not be their main source of income, but it often is,” explained Ismene Gizelis (below), professor of government at the University of Essex, which in 2016 was the first UK university to introduce staff status for PGRs. Those PGRs who accept more paid duties outside their studies risk rendering themselves uncompetitive in the academic job market that they ultimately wish to join, she continued.

“When we advertised a job here last year, we had 100 applicants, many of whom were doctoral graduates from the US, who had four or five publications in top journals – if you’re also teaching a lot, it’s difficult to compete with these people,” said Professor Gizelis, who is director of the South East Network for Social Sciences, a doctoral training partnership involving 10 universities that is funded by the Economic and Social Research Council.

Reducing the number of self-funded PhD candidates in UK universities while also increasing funding to support PGRs would be a better way to reduce precarity, insisted Professor Gizelis, who said Britain’s PGRs lacked not only the security of the more expensive Dutch-Scandinavian model of PhD employees but also the benefits of the US system, where relatively fewer numbers of PhDs students study for longer, usually five to six years full-time, which leads to a better research experience and employment outcomes.

“The UK has the worst of these two worlds – if you want to address precarity and inequalities, I cannot see how you do this unless you reduce the number of self-funded PhDs entering a job market where demand is clearly less than supply,” she said.

Essex’s decision to treat PGRs as staff may have been lauded, but the pandemic showed how this policy could backfire as teaching assistants had, in some cases, found it difficult to pay living costs or PhD fees after losing teaching hours, said Professor Gizelis. “It was quite revealing – graduate teaching assistants were in a very difficult situation when their fixed-term contracts were not renewed,” she said.

For Mr Kirby-Reynolds, this and similar situations across the country demonstrated why PGRs “deserve to have the rights and entitlements to security that other workers have”, which may alleviate precarity.

Changing the status of PGRs to staff might, however, create different problems for early career researchers, said Jenny Iao-Jorgensen, chair of the National Swedish Doctoral Candidate Association and a second-year doctoral student at Lund University.

“It’s very important to get this universal recognition, but it can lead to less positive side-effects,” said Ms Iao-Jorgensen.

In Sweden, the association was keen to stop the creation of “shadow doctoral candidates”, whereby universities employed cheaper “project assistants” or technicians on fixed-term contracts to do work typically performed by PhD candidates in their research groups.

Her advocacy group is part of Sweden’s main academic union, the Swedish Association of University Teachers and Researchers, where PGRs are given particular prominence, and she was glad to see the UK’s union taking a similar interest in this group. “Our union recognises that we are a special group who are especially vulnerable to being exploited but also contribute a lot to academic life,” she said.

While the pay and conditions of UK PGRs might not measure up to their European counterparts, many British universities might justifiably point out that many of the UCU’s demands are already in place at their institution. For instance, the University of Surrey’s code of practice states that “postgraduate researchers who support teaching are considered a part of the support teaching team” and because “teaching support duties are optional…postgraduate researchers cannot, therefore, be required to undertake teaching support duties as a part of a scholarship agreement”.

Kate Gleeson, dean of Surrey’s doctoral college, said it was important for the university to “value [PGRs’] contribution to teaching and to our research culture” and to “signal [this] value placed on their contribution by paying for time spent demonstrating, marking and in preparation”.

She was, however, hesitant about viewing PGRs in exactly the same terms as faculty. “Even if we regard PGRs as colleagues who make important contributions to our research culture, we also feel that we hold an important duty of care that is more akin to the duty to a student,” said Dr Gleeson. This “reflects their unique position as researchers at the beginning of their career”, she explained.

“You only get one opportunity to begin as a researcher, and it is vital that we protect that experience,” said Dr Gleeson.

The road to recognition of PhDs as staff is likely to be a long one in the UK, as it has been in the US, where many top universities have fought hard against the idea because it would also mean greater union recognition for graduate teaching assistants.

“Universities resist because of both fringe benefit costs, which are covered by the state in Europe, and wages, but also because [it would strengthen] the voice of the employees who seek to improve their conditions,” said labour scholar William Gould, an emeritus law professor at Stanford University.

Even in Europe, the fight is far from won, says Eurodoc’s Dr Malaguarnera, who claimed that “only the Netherlands has good employment conditions considering the doctoral candidates as professional”.

In Sweden, where employee recognition was granted in 2017, the campaign lasted decades, said Ms Iao-Jorgensen. “It does not happen overnight, and our union campaigned for this since the 1960s – it will be a long struggle but it will be worth it.”

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Should postgraduate researchers come under staff umbrella?

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?