So, he meant it. All those wild campaign pledges that were written off as rabble-rousing rhetoric that would be quietly forgotten once Donald Trump was in the Oval Office? Well, we can’t say we weren’t warned.

The president’s executive order banning entry to the US of citizens from seven Muslim-majority countries was yet another escalation of the Trump worldview, and one with enormous implications for higher education.

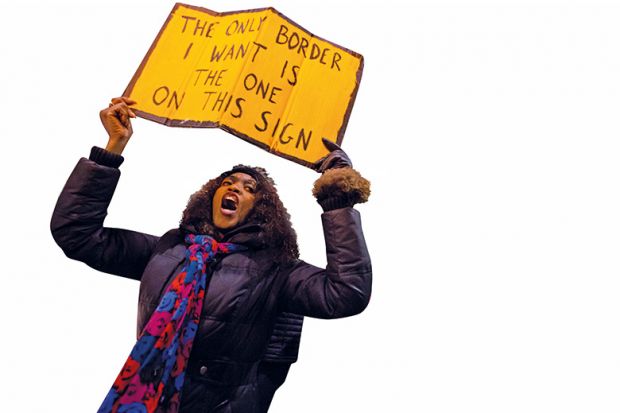

On a purely practical level, the very biology of universities is international. Their bloodstreams flow with ideas and people from around the world. Research is collaborative. Education should be transformational. If talent, hard work and merit are trumped by religious background, then how can either hold true? The order, issued last weekend, provoked an immediate outcry from academics. Students and scholars based in the US but with birth certificates not to Trump’s liking were left stranded around the world. “This is simply inconceivable,” said Esther D. Brimmer, executive director and chief executive of Nafsa: Association of International Educators. “The latest executive order, egregious enough in its aim to suspend the refugee program…has also caused enormous collateral damage.”

Few in academic circles will disagree. But what is the appropriate – or more importantly, most effective – response to what is emanating from the White House?

One of the lessons of the past 12 months is that denunciation is not enough. Trump is in power because he said he’d do the things that he is now doing.

As Sir Keith Burnett, vice-chancellor of the University of Sheffield, put it in an email to staff this week: “There will be many who support the action by President Trump and see it as the only way to defend their country, and we cannot dismiss their concerns. It is rather our duty to show why we believe this to be deeply counterproductive to the purposes of peace and freedom.”

How to do this in a way that defends the values that define a university is, of course, the tricky bit.

In our cover story, we focus on the world’s most international universities, but as Lino Guzzella, president of ETH Zurich – Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich, says: “Being international in itself is not the goal.” The goal is excellence, and that cannot be achieved in any of the core areas of university activity without a strong international outlook.

Setting the strategy is one thing, but universities also need the environment to flourish on the global stage. Funding is vital to compete for academic talent. A political and cultural environment that is open to the world helps, too. It’s no coincidence that the upper echelons of the tables we publish this week, showing the 150 most international universities, are dominated by relatively small, export-oriented countries where English is either the national tongue or is widely spoken. Universities in Switzerland, Hong Kong, the UK and Australia all feature prominently. The US, by contrast, is some way behind, even in the years before Trump.

To be worthwhile, internationalisation must be organic to a certain extent. Research collaboration comes from those at the coalface, not from senior managers. And the evidence shows that internationally co-authored papers tend to have higher citation impact.

Turning to students, it’s clear that the movement of people to study in a country other than their own has become one of the defining characteristics of higher education in the past decade or two.

These nomads bring money into universities – there’s no point denying that. But they also bring countless other benefits, helping universities to live up to their billing as transformational places.

It’s no surprise, given the trajectory of politics in the US and the UK in particular, that the obituaries are being written for the age of globalisation. But politics is never permanent, and there is work to be done. Musing on academic pessimism in our Opinion pages, Shahidha Bari, lecturer in Romanticism at Queen Mary University of London, argues that “it seems entirely possible to think (and teach) truthfully and constructively through bleak times”.

Others feel that reports of globalisation’s death are, in any event, exaggerated. “It’s too hard-wired now,” says Sir Eric Thomas, former vice-chancellor of the University of Bristol, in our cover story. “The economic and cultural drivers for a globalised, interconnected world are so strong that I don’t see that we are going to retreat from that.”

Guzzella is right when he says that internationalisation isn’t an end in itself for universities. But it is a bulwark against the parochialism that seems to have gained in confidence over the past 12 months. And for universities, reverse gear wouldn’t be merely undesirable, it’s hard even to see how it would be possible without accepting catastrophic decline.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: One world, like it or not

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?