The links between African and Western higher education run deep. Although centres of advanced learning – such as Al-Azhar in Egypt and Timbuktu in Mali – existed prior to the arrival of Europeans, Africa’s current tertiary institutions originated in the colonial era; pioneer universities such as Uganda’s Makerere, Nigeria’s Ibadan and Sudan’s Khartoum developed as embryonic overseas colleges of the University of London, for instance.

Furthermore, despite the wave of nationalism and independence movements that swept the continent in the 1960s, African universities continued to be associated with their European and American partners – and Western universities continued to be the prime destinations for African students seeking better quality higher education. Most African academics typically received their postgraduate training in the US, the UK or France.

Yet in recent years a remarkable transformation has occurred. While France continues to be the most popular destination by far for African students, United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation figures indicate that there are now more African students in China than in either the UK or the US. Student flows from Africa to China, which began with a trickle in the mid-1950s, have risen exponentially since the turn of the millennium, surpassing 40,000 a year by 2014. These students are enrolled on a wide range of degree programmes – including doctorates in English language!

This incredible development, which may represent the dawn of an era, is the result of several factors. One is the enduringly unfavourable economic conditions in sub-Saharan Africa, which have reduced the number of students able to afford a Western education; the relatively low fees mean that two-thirds of African students in China are self-sponsored. Another is the steady tightening of immigration rules in the West since the 1980s. More recent factors include Brexit and the election of Donald Trump, both of which are perceived to be characterised by xenophobia and hostility to migrants.

The flight of African students to China is also impelled by Africa’s domestic inability to meet the enormous demand for tertiary education. Although the continent has witnessed a considerable expansion in provision over the past two decades, it has failed to keep pace with rapid population growth. Of Africa’s estimated 1.3 billion people, nearly 500 million are between the ages of 15 and 24: no wonder, then, that the continent’s tertiary enrolment ratio of 14 per cent is the lowest in the world.

Even where higher education provision exists, its quality is often appalling. Sub-Saharan African countries in particular face a colossal shortage of people trained in science, technology, engineering and mathematics. The African Union is concerned that this will pose threats to the continent’s ability to meet socio-economic development targets, such as its Agenda 2063 and the United Nations’ sustainable development goals – the latest iteration of which stipulate that an “inclusive quality education” be attained by 2030.

The only hope, then, lies with China. The quality education and modern infrastructure offered by its universities is a pull factor for many African students – particularly given the growing number of Western-trained Chinese academics returning to the country. During a conference I recently attended in China, as part of a large Pan-African delegation, some of these academics presented papers in English. I also learned that some Chinese universities have appointed professors from universities in South Africa and Tanzania.

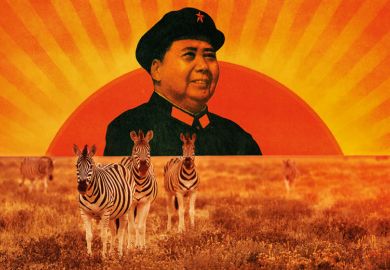

China appears to be boldly seizing the opportunity in the current global climate to advance its economic and cultural interests around the world. This is particularly true in Africa, where it offers many scholarship programmes – in line with the Belt and Road Initiative and the strategic South-South partnership agenda of the Forum on China–Africa Cooperation.

This is further promoted by the Confucius Institutes that have sprung up in many African countries. These are not yet on the same footing as Western equivalents such as the British Council or the Goethe-Institut, but the intention could not be clearer: China has Africa in its sights.

The result could well be that while Africa’s 20th-century intellectual giants were largely educated in the West, the 21st century’s Cheikh Anta Diops (Sorbonne), Wole Soyinkas (Leeds), V. S. Naipauls (Oxford), Ali Mazruis (Manchester and Oxford) and Léopold Sédar Senghors (Sorbonne) will emerge from Chinese universities.

Kuyok Abol Kuyok is an associate professor of education, University of Juba, South Sudan.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: On a speed boat to China

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?