Universities must adopt new measures and incentives to deliver on the promise of interdisciplinary research, sector leaders have said.

Michael Spence, vice-chancellor of the University of Sydney, told the Times Higher Education World Academic Summit that his institution had introduced “non-traditional” metrics for its multidisciplinary initiatives. He cited the Charles Perkins Centre, a six-year-old institute harnessing researchers in fields as diverse as medicine, biology, business, architecture and agriculture to tackle the related scourges of obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

“We said the only metric was going to be the extent to which it changed Australian incidence rates and led to better forms of treatment,” Dr Spence told a breakout session at the summit, held at the National University of Singapore.

“It wasn’t that we stopped counting Nature papers, [but] we created different internal incentives that were outward-focused. That’s had a big cultural shift on the institute, and sort of made it more fun.

“Interestingly, it’s also meant that people are less tolerant of the person who does sod-all, because you’ve got to be making some contribution. It’s lifted our performance as well as had that cultural impact.”

Dr Spence added that when everybody in a research institute had the same expertise, things tended to become “boring”.

“You want to be in an environment where your cutting-edge work on artificial intelligence is being challenged by a political philosopher who is saying ‘this is the end of civilisation’, in a structure that encourages you to work together meaningfully,” he said. “And you want to see your work make a difference.”

Fellow panellist Evelyn Welch, provost of King’s College London, said that yardsticks made a difference in the higher education sector. “You get what you measure,” Professor Welch said.

The sector had become “acclimatised” to global rankings since Shanghai Jiao Tong University produced the first international league table in 2003, she explained. “If we produced another set of rankings based on the immediate poverty levels around our campuses – ranked all institutions based on the per capita income within a 15-mile [24km] radius, and said that was the way we were going to measure ourselves – universities would move fast,” Professor Welch said.

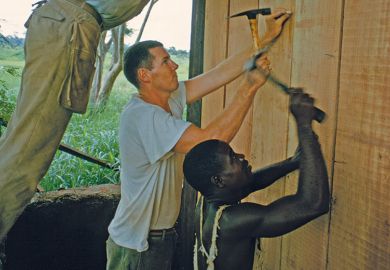

When research funding was directed towards grand challenges, she added, interdisciplinary communities formed naturally. “It’s worth challenging the notion that universities are hidebound ivory towers. We respond very well to the right kinds of incentives that allow us to keep our curiosity going.”

Pam Benoit, provost of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, said that pressure for interdisciplinary work was coming from students as well as from research imperatives.

“You have to have strong disciplines, but you also have to give students the kinds of things they’re interested in,” she told the forum.

Thiam Soon Tan, president of the Singapore Institute of Technology, said that “real-world” issues – in allied health, for example – inevitably required input from different disciplines.

“We are beginning to work with the community hospitals, thinking about rehabilitative healthcare in the community. It doesn’t take very long to realise that you need IT people, engineers – even accountancy and finance people – to come up with simple solutions,” he said.

“When you start with a real problem, very soon the problem itself will lead different people together.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?