Weaving and hoarding

There’s a striking moment in George Eliot’s 1861 novel, Silas Marner, when the miserly weaver is described as being so entirely reduced to the “functions of weaving and hoarding” that his face and figure shrink and bend themselves into “a constant mechanical relation to the objects of his life”. Marner works his loom and counts his coins, withering into the shape of his toil; his eyes, which used to look “trusting and dreamy”, now appear as if “they had been made to see only one kind of thing that was very small”.

Eliot imagines Marner’s diminishment as commensurate with that of others who are isolated from community through their self-absorbed attention to work. She writes that the same process has been “undergone by wiser men”, who, instead of “a loom and a heap of guineas”, have “some erudite research, some ingenious project, or some well-knit theory” that narrows and hardens their lives into “a mere pulsation of desire and satisfaction that [has] no relation to any other being”.

Substitute “weaver” for “academic” and “guineas” for “research outputs” and the picture is familiar enough. Academia often encourages a kind of hoarding and miserliness; our ideas must be protected and tallied, and, like Marner, we are reduced to mere functions. We too are shrunk and bent in relation to our function, and our dreamy trust in colleagues is replaced with a more cynical and narrow strategic vision. Our participation in community is always fraught, since what we are taught to desire is only our own good; collegiality is always tinged with suspicion and jealousy.

But not always, and not inevitably.

In 2014, I travelled to the US to give a series of conference papers. I had just submitted my doctoral thesis and the trip was designed in part to make the best of my final funding opportunity before I was cast adrift. I suspect I am not alone in experiencing post-submission terror: my office access was revoked, my scholarship was ending and the yawning gap between a PhD and tenure was unnervingly clear. The community to which I belonged was revealed as fleeting; the PhD was extracted, and I, having been twisted into its shape, was left to fend for myself.

I had scheduled conferences in North Carolina and Indiana, and so drove in a big, isolated loop: north through the whiskey trail, east across cornfields, south through coal country, and finally back to the pine forests of North Carolina. The stop in Indiana was nightmarish: I left with a stock of morbid party stories and a deep sense of the futility of the whole enterprise.

During the trip, however, I had sent an email to an eminent professor in Ohio. Despite not knowing her – despite being a mere postgraduate – I suggested that we meet to discuss a paper she had published, and which I had loved. She promised breakfast (her shout!) and expressed deep gratitude for my earnest email. We met and talked, and she listened and cared and did all of those things that humble people do, who help you see yourself more clearly and more generously. Eventually, much later, I left, feeling genuine joy. I felt connected to an invisible community of morally serious and thoughtful scholars. Her generosity was a life-preserver.

Like any good fairy tale, Silas Marner offers a picture of the world set right again. Eppie, the golden-haired orphan who arrives on Marner’s hearth, forces the weaver to see more clearly: she redeems his vision. Eliot writes that “the gold had kept his thoughts in an ever-repeated circle, leading to nothing beyond itself; but Eppie was an object compacted of changes and hopes that forced his thoughts onward”. Marner comes to know joy because Eppie knows joy, and her intervention reawakens his senses with fresh life.

The gift of that professor in Ohio was modest enough in academic terms: time, care, acknowledgement. But it was also miraculous. It was an act of love. If we want to unbend and unshrink ourselves in academia, we could do worse than look for ways of enacting generous kindness.

Jedidiah Evans is an associate lecturer in the department of writing studies at the University of Sydney.

The wrong room at the right time

It seems likely that most of the unexpected acts of kindness that occur in academia are instances of considerate colleagues just being themselves at a moment when we ourselves are feeling particularly overwhelmed by academic life.

In my experience, one particular example stands out as an act of kindness that meant far more to me than my kind colleague ever realised.

On my first day of teaching at Denison University, I walked into the classroom for my Reformation history seminar, only to discover that it was a space meant for science lab classes. Not only was it not possible to rearrange the furniture to accommodate a seminar-style discussion, there weren’t enough chairs for all of my students to sit down. There was a long counter between the students and the chalkboard. Nothing about the room said: “Let’s sit together and exchange our thoughts about Reformation history.”

I had not visited the classroom ahead of time, as perhaps I should have. The previous six years leading to that moment had been tumultuous ones, including choppy professional waters, the challenges of a dual academic marriage, the deaths of two parents, the sleepless phases of parenthood and a difficult family relocation.

As a result, on that first day of classes, it had been all I could do to navigate the morning rituals at home, get two small children to school and then to drive the 30 miles to start fresh with new students at a new school. It had never crossed my mind to find the time to inspect my classroom.

As I was wandering through the hallway in search of more chairs, a physics colleague stopped and asked if he could help. I explained my predicament. When I told him that I was in the history department, it seemed clear to him that there had been a scheduling mistake. He helped me find chairs, explained how to request a room change, and went on his way.

I made it through my first class and walked back across campus to the history department. When I got there, I went to ask our administrative assistant to help me find a new room. She began to search but warned me that classroom space was at a premium and that I might not be able to find anything.

Preparing for the worst – as had become my habit at that point in my life – I was already contemplating how I could run a seminar in a science lab. But when the administrative assistant pulled up my class information, we discovered that the room had already been switched to a lovely classroom in the English department.

Rather than simply continuing on with his day, my new physics colleague had evidently decided to resolve my classroom situation for me. Knowing the way Denison worked and the competition for classrooms, he had chosen not to leave the situation hanging until I finished my class. Instead, he had taken it upon himself to help me get off to a good start by making sure that my class got moved to the kind of space I needed.

I have no doubt that, to him, this was just the obvious solution, easily taken care of. But, to me, on that particular day and at that particular moment in my life, that small act of kindness provided invaluable reassurance that I had landed at the right place. And it set a model that I continue to try to follow in my own daily interactions with colleagues.

Karen E. Spierling is director of global commerce, associate professor of history and inaugural John and Heath Faraci endowed professor at Denison University, Ohio.

The gift that keeps on giving

This act of academic kindness occurred some years ago, but I only heard about it recently, from its beneficiary. She was teaching part-time at my university when, at short notice and in the middle of the marking season, she was shortlisted for a full-time post at another institution. Two of my colleagues – one a full-time lecturer, the other part-time herself – took all her marking off her so that she had time to prepare for her presentation and interview.

In their book On Kindness (2009), Adam Phillips and Barbara Taylor argue that kindness is now seen as “a virtue of losers”. They attribute this to the ascendancy of free-market individualism, which has cultivated competitiveness and mistrust and led to “a life of overwork, anxiety, and isolation”.

If they are right, then kindness should also be endangered within the university. The new managerialism urges us to see ourselves as hard-nosed entrepreneurs competing for awards, grants and research time, while also making us feel that no amount of success will ever appease the gods of compliance. It makes the modern university not so much a cruel as a callous place, one where feeling harassed and stressed makes us thoughtless and self-absorbed. We are rarely unkind on purpose, but being unkind by accident usually has the same effect.

What is remarkable, though, is the doggedness of our desire to be kind. There is still room in academia for what A.H. Halsey, in The Decline of Donnish Dominion (1992), calls “commensality”, which literally means sharing a table and which he uses to mean that intangible sense of collegiality on which we thrive. Universities would grind to a halt without these millions of small, inconspicuous acts of goodwill.

In this season of gifts, we should remember that kindness is a kind of gift. In his book The Gift (1983), Lewis Hyde argues that the giving of gifts has been the driving force of civilisation. The gift economies of remote tribal societies worked by constant circulation. The seafaring peoples of the western Pacific made long, perilous boat trips to other islands to exchange bracelets and necklaces made of shells. They treasured these trinkets, which had little intrinsic worth, because of the network of relations they symbolised as they moved round the islands. A commodity loses value if it is second-hand, but this kind of gift gains value the more hands that have held it. It can never be stockpiled or sold, but must be constantly given away.

Kindness is this kind of gift – the one that keeps on giving. It still puzzles me when, after I have done them some small favour, people say “I owe you one”, especially since in practice they seem to mean: “Thanks for your help, which I will now erase from my mind as if it never was.” The whole point about kindness is that it can’t be contractually binding or straightforwardly reciprocal. Like the Catholic notion of grace, it only works if it is dispensed wholesale, regardless of the deservedness of the recipient. It can never be owed or paid back, only given away. The gift of kindness is all the more precious for not being neatly wrapped, tied with a ribbon bow and handed over to someone you know. Instead, it is sent out into the world to be found.

The person whose marking was done for them got the job she had been shortlisted for, and remains in that post. When I saw her a month ago, she still seemed touched by this simple act of kindness, given in the true spirit of a gift – without counting the cost.

Joe Moran is professor of English and cultural history at Liverpool John Moores University.

A priceless investment

In the fall of 1991, I spent a semester abroad, at Queen Mary University of London. My first journey beyond the US was to be a pivotal time: I envisaged myself making many new friends, bringing home terrific grades, and perhaps scoring a few London fashions to wear at my small, liberal arts college in Arkansas.

Nothing of the sort occurred.

First, I was gobsmacked by a novel concept: currency exchange rates. With no internet to study my new home for the next semester, I had overestimated my spending power. My funds were in effect halved when converted into pounds. Also, with no ability to easily research transportation, I did not realise that my campus would be a good seven miles from my residence; at home, I could walk to classes in minutes. So my funds were immediately reduced again by the cost of a three-month Tube pass.

Next, I did not anticipate being on my own for so many meals. The dining hall provided breakfast during a narrow time window in the morning and offered dinner if I was back from campus by 5pm. This was problematic because I was required to study a foreign language, physics and three science classes in one semester – something apparently atypical for the Queen Mary system at that time. Thus, my classes were at inconvenient locations and times, forcing me to resort to pricey London fast food or questionable grub at the student union.

By the time I’d rebudgeted for a new raincoat, books, paper (who knew about A4?) and a bookbag to haul everything to campus each morning, I had almost no money left. I wasn’t even sure I would be able to afford the trip back from Heathrow in December. I was very afraid.

Then, approximately two weeks into the semester, we were required to purchase a laboratory kit for dissections, experiments and other exercises that would extend beyond my departure, into the spring semester. I baulked at purchasing something that I’d only use for two months, but the instructor, whose name I have ungraciously forgotten, suggested that my grades would suffer if I did not make the purchase. This deflated me – a final insult to my cold, often wet, constantly hungry self. It felt to me as if my academic abilities would be judged by my lack of money and not my effort. I burst into tears and left.

I was halfway down the hall when I heard her call me back. When I entered her office again, she had a chequebook in her hand. She scribbled a moment, tore out the cheque and handed it to me. Then she directed me to the bookstore.

“Use this to get the laboratory supplies you need,” she said. “Then, I want one thing from you. When you are finally successful back in the States, you must do something similar for a student like you.”

Incredibly embarrassed but enormously relieved, I thanked her inadequately and did as she directed. I made it through the semester with grades good enough to send home and a small feeling of accomplishment clouded by humility.

I think of this woman often. Our almost 40,000 undergraduate students are often as poorly prepared for the college experience as I was for studying abroad. Indeed, many new things for our students come as unpleasant surprises. Therefore, when I notice one of them struggling academically, socially, financially or emotionally, I invite them for a quick lunch, or I hang around before or after their class to engage them in conversation.

Talking and listening cost nothing, but they are a valuable offering. This way, I can honour the request of the generous professor at Queen Mary, multiplying her spontaneous act of academic generosity. I only regret that she will never know.

Jennifer Schnellman is associate professor of pharmacology at the University of Arizona.

Kicking against the me, me, me

It’s exactly one month to Christmas Day as I write this. Academics and students alike should be drafting their letters to Santa and looking forward to the festive season after toiling all term in lecture theatres, seminar rooms, workshops and – very occasionally – libraries.

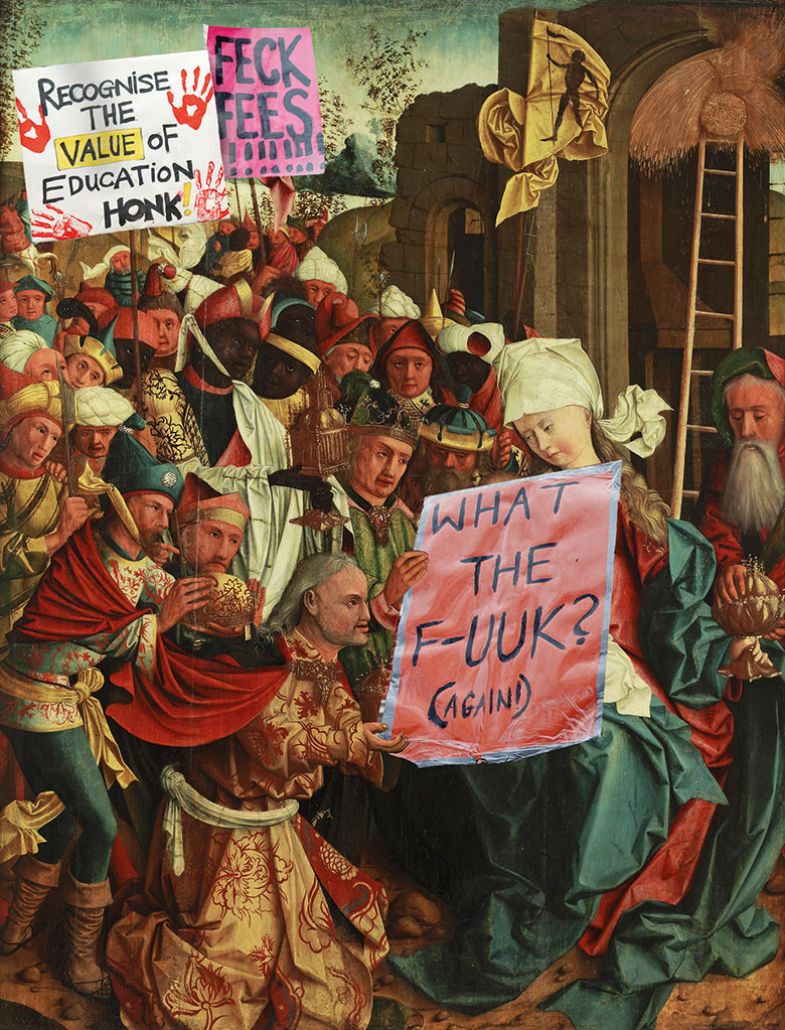

Except that today is also the first day of the latest round of strike action by members of the UK’s University and College Union. This time, the issue isn’t just pensions: the strike is also in protest at pay, equality, casualisation and workloads. But universities’ reactions are familiar from the previous strike in 2018, with reports of draconian measures being taken against not only striking staff but also, unforgivably, students who support them.

It is clear that senior management and rank-and-file staff are unlikely to be on each other’s Christmas card lists this year. Nonetheless, in these days of ever-increasing and ever-more-infuriating corporatisation and depersonalisation of universities, it’s important not to lose sight of the collegiality that still exists, and the sense of community that is fostered when students and staff (of all stripes – from the cleaners to the professoriate) look out for each other.

This has certainly been the case during my 25 years in the University of Nottingham’s School of Physics and Astronomy. Indeed, the often-clueless, metrics-driven management style foisted upon us from on high results in an “us versus them” mentality that only serves to bring us even closer together. I hesitate to use the hoary old Dunkirk spirit cliché, especially in these days of Brexit-inspired Little-Englander fervour, but it certainly captures that sense of fighting back from the chalkface. In solidarity.

It’s the little things that matter most: those seemingly small acts that cultivate a culture of kindness, kicking against the me, me, me of metrics and the tediously relentless pseudostatistics of league tables. I’ve lost count of the number of times that students and staff have gone the extra mile to brighten up someone else’s day, week, month or year. Examples range from the tea-room coordinators who put aside particular fruit, biscuits and cakes because they remember just what each member of staff likes with their beverage of choice for “elevenses” (Anna, we salute you!) to the tutees who turn up with gifts, cards and messages of thanks for their tutor; the anonymous faces in the lecture theatre who take the time to nominate members of staff for various teaching awards; and the graduates who email unexpectedly, years after they finished their degrees, to describe how fondly and gratefully they look back on their time at university.

Sometimes these random acts of kindness make you smile. And other times, I’ve been moved to tears. A couple of years ago, I was in the middle of a phone call when a knock on the door interrupted the conversation.

“Just one second!” I called out, and finished the call as quickly as I could. When I opened the door, there was no one there. But at my feet there was a big box of chocolates and a card containing the simple message: “Thanks for everything”. It was from a student who was severely autistic, with whom I had communicated almost exclusively via email over the years of their degree.

Forget my latest publication, or research grant, or citation count. That simple message meant so much more.

Philip Moriarty is professor of physics at the University of Nottingham.

Radical humanity

Once upon a time, I was told that “kindness is a bonus” in the academic workplace; all we owe to one another is “professionalism” – whatever that means.

I’ve never believed that. But nor do I quite concur with those who speak of academic kindness as a strategy for survival amid an inhuman, neoliberal ideology of overwork and competition. I think it can be more substantial and meaningful than that.

Practising kindness is about embedding a culture of ethical, non-hierarchical and respectful action in our everyday spaces, such that we are supported and cared for in our day-to-day interactions, practical labour and intellectual work.

But what does it actually mean to “do kindness” within academic spaces? How can we take the idea of kindness and enact it in ways beyond performative things such as smiling or socialising with our colleagues? I’ve had some excellent teachers and co-conspirators who’ve guided the way.

My PhD supervisors, Heidi and Michaela, set the example early on in my career. One of the first things they suggested that I do (and we all know that this means “do it”) was to create “sanctuary space”: a protective calm to buffer against the stresses and frictions of academia. So in our supervisions we talked books and food and TV – swapping recommendations, reviews and French macarons.

It seems so trifling, but knowing one another’s tastes, inclinations and allergies is an ever-present reminder that what you’re doing in an academic relationship is predicated on emotionally engaging with another human being. It let us be more straightforward, open and truthful with each other – which itself reinforced our ability to act with care for one another. This sensitivity and generosity created bonds of community and trust, meaning that supervisions were safe and supportive spaces for everyone.

One of the joys of my academic life is my partner in crime, aka my co-author, Vikki. A few years ahead of me career-wise, Vikki has been instrumental in demonstrating that you can be a serious intellectual scholar while also giving and receiving kindness. The way she practises a feminist ethics of care means that every bottle of wine we open is an opportunity for cathartic sharing and intellectual analysis – without one ever outshining the other – and for seeing our experiences and perspectives reflected in one another without ever being minimised. There’s real solidarity in knowing that you don’t have to explain yourself to be understood.

I’ve found this more recently with my office mate, Emma. Academia is rife with abuses and violence, and one of the kindest acts possible is to simply believe someone when they tell you of their experiences, without requiring any intimate detail or proof. This is also “sanctuary space”, and I will be forever grateful to Emma for her part in this.

Academia is, more often than not, harsh and unforgiving; it has even been described as an “anxiety machine”. The constant recourse to narratives of professionalism that obscure and dismiss selfhood and feeling asserts, in effect, that we must be less than ourselves when we are at work. Conversely, the ongoing acts of kindness I’ve experienced have taught me that academic work actually requires the robustness and vulnerability of the personal.

Ultimately, this sort of serious, radical kindness is a recognition that we are always more than our jobs, and that our humanity does not exit our personhood when we enter our workplace.

Sarah Burton is a Leverhulme early career fellow in the department of sociology at City, University of London.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: The gift of kindness

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?