Fostering stronger links between business and universities has been high up policymakers’ wish lists in the past decade as they search for cures to the stuttering growth seen in many Western nations since the global financial crisis.

Phrases such as “knowledge exchange” (or, if you prefer, “knowledge transfer”) have never been far from the agenda as the advocates of universities as engines of economic growth plead what they see as an open-and-shut case.

The importance of industry-academia links was evident in the UK’s Industrial Strategy, published at the end of November, in which hopes for post-Brexit economic growth were pinned on areas in which British university research is strong, such as the life sciences and artificial intelligence.

An emphasis on such an approach is sure to feature among discussions at this week’s annual get-together of the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, an event that has in recent years seemed like an annual crisis meeting about the state of capitalism and the best way to refuel the engines of global growth.

To coincide with the meeting, Times Higher Education has, with the help of Elsevier, taken a deep dive into the data on industry collaboration for the institutions that form part of the forum’s own “community” of universities, known as the Global University Leaders Forum (GULF). This includes the presidents and vice-chancellors of many of the world’s most influential higher education institutions, including Harvard and Stanford universities, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the universities of Oxford and Cambridge.

From Davos: THE reports from the World Economic Forum 2018

While the analysis reveals some startling facts about the economic impact of these universities, it also raises important questions about the nature of industry-academia collaboration and whether it could be better leveraged to benefit more industries and countries than it does at the moment.

The GULF, set up in 2006, is currently made up of the leaders of 27 universities from 11 countries. According to Jaci Eisenberg, the World Economic Forum’s lead for university engagement, members – which are selected jointly by the WEF and existing GULF members – are those institutions recognised in global rankings as “leading research establishments, as well as those with which [the WEF has] developed strong working relations over the years”.

Because of this, its membership is dominated by US institutions, and it contains every university in the top 10 of the THE World University Rankings 2018. Eisenberg explains that the group is expanding its geographic representation and it does already include members from countries with less-renowned research systems, such as South Africa’s University of Cape Town. Even so, the average THE ranking score of the GULF’s members (discounting Bocconi University, a private university in Milan that is the only GULF institution not in the THE ranking) is 80, which if it were a university would place it at 25th in the 2018 list.

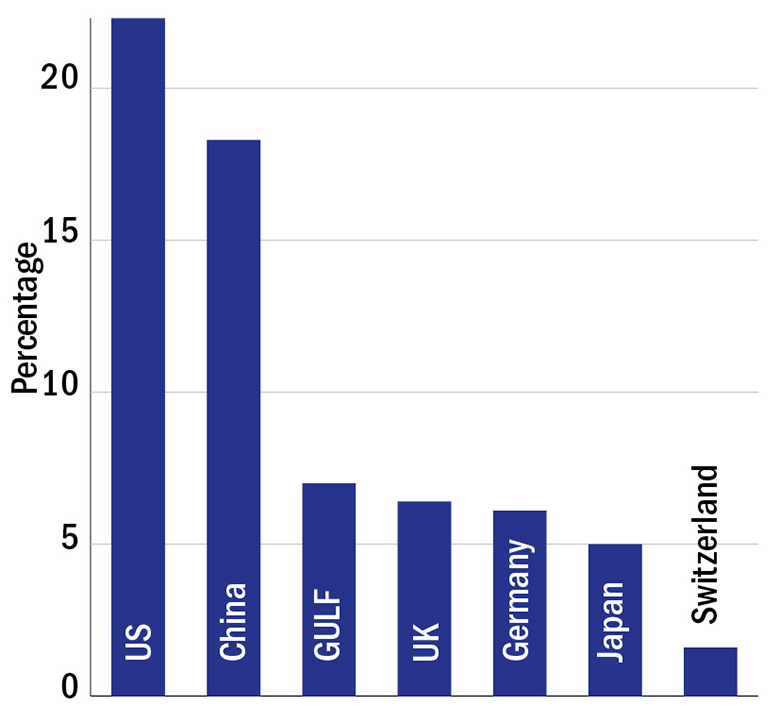

The Elsevier data demonstrate even more clearly the impact that the GULF group has on world research. The universities were involved in 7 per cent of all published research indexed in the company’s Scopus bibliographic database between 2012 and 2016: “a share that is higher than some major research nations like the UK (6.4 per cent), Germany (6.1 per cent) and Japan (5 per cent)”, according to M’hamed el Aisati, vice-president for funding, content and analytics at Elsevier (see graph below).

Share of world research, 2012-16

GULF universities compared with selected countries

Source: Elsevier

In terms of research volume, it is Harvard that leads the GULF pack by some distance, being responsible for almost 120,000 pieces of research during that five-year period: about twice as many as Tsinghua University, the institution that comes second.

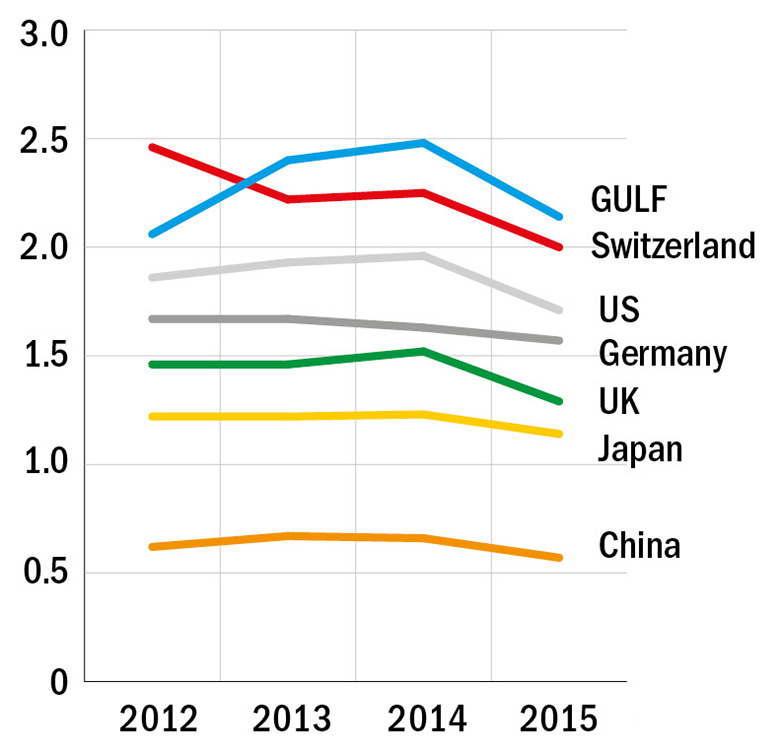

The group’s impact on commercialised inventions and discoveries is even more eye-catching. Taking all the citations made in worldwide patents of research published over the period, research by GULF institutions is cited about 16 per cent of the time, second only to the US (whose institutions feature in more than 40 per cent of citations). And, relative to the number of publications produced by each nation, the GULF group has a patent-citation rate that is higher than that of any major research nation, and twice the world average (see graph below).

Research that works

Patent citations per publication, 2012-15. GULF universities compared with selected countries (world average = 1)

Source: Elsevier

Unsurprisingly, there is also evidence of private-sector interest in the group’s research output. Of all the papers published by the group in the period 2012-16, the proportion downloaded by firms ranged between 14.8 per cent and 16 per cent: this was higher than the share seen for global research as a whole, despite most GULF universities focusing on basic rather than translational research.

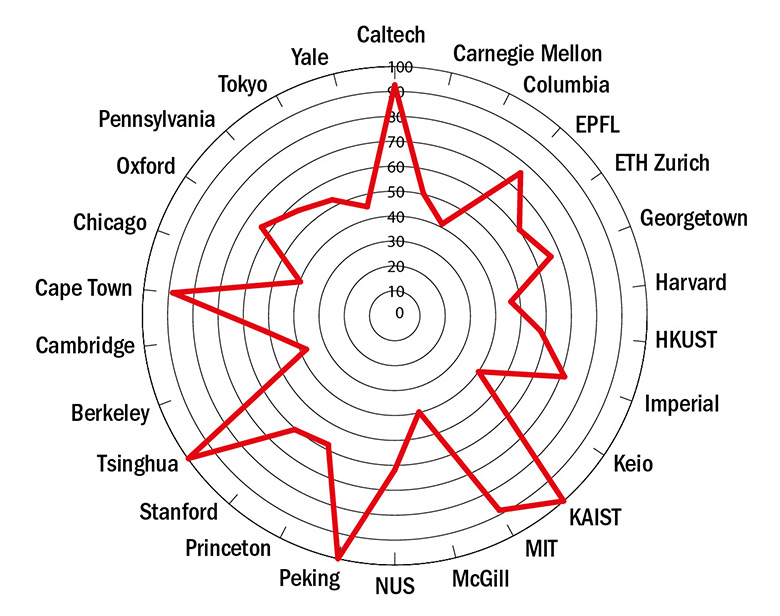

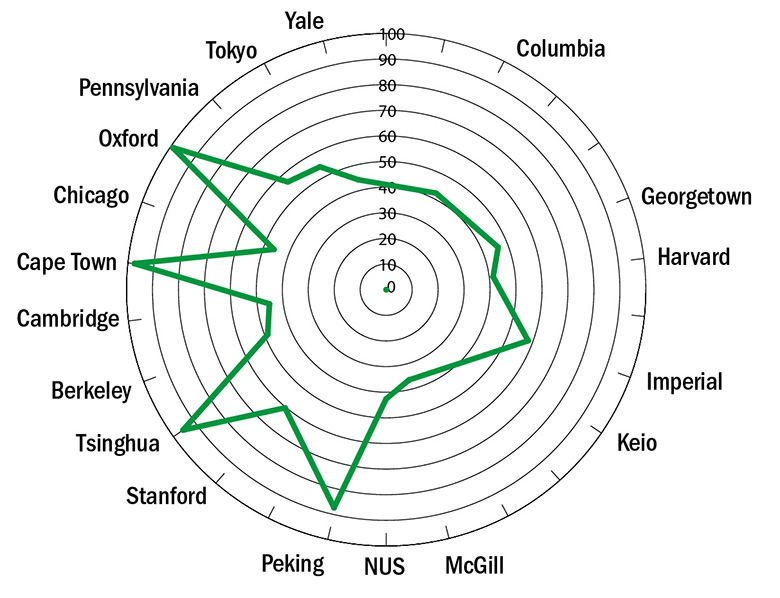

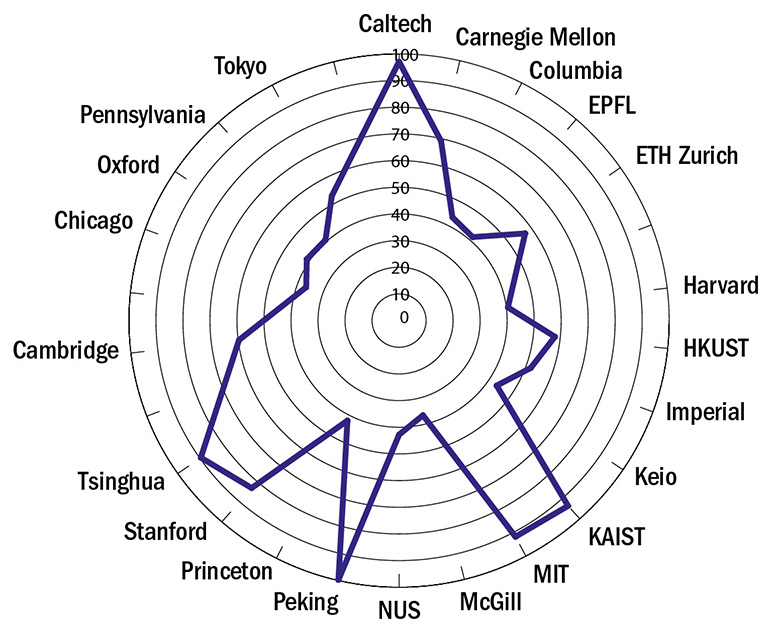

THE’s own data show that, relative to other universities, some of the GULF institutions are also among the top earners in terms of income from industry sources. The East Asian universities dominate here because of the large proportion of funding for higher education that comes from industry in countries such as South Korea and China. However, the California Institute of Technology and Cape Town also score well. And looking at specific subject areas shows other GULF universities leading in different fields for industry income: Oxford is top in clinical fields while Caltech and MIT lead on computer science (see spider diagrams below).

Scores for industry income in 2018 THE rankings by subject

Overall

Clinical, pre-clinical and health

Computer science

Source: THE DataPoints

Note: Universities are in the same position on the dial in all three images. As not all universities are represented in each category, this results in some gaps

So it is clear that for the GULF members, industry collaboration is a two-way street. But how do these relationships form? Are they instigated by universities seeking funding alternatives? Or by firms looking to gain an R&D edge? And do they confer any other advantages beyond the financial sphere?

According to Nick Jennings, vice-provost for research and enterprise at Imperial College London, it is nice if industry collaboration creates income for the institution – through the commercialisation of research discoveries, for instance – but it is certainly not the main aim of the work done at Imperial.

“It is fantastic if we generate things that make money, but that is not true of most industrial research or spin-outs. We are much more interested in it for the impact it makes – and that can be a virtuous circle,” he says. “When you [as an academic] want to apply something in the real world, you often find that your super…method or technique doesn’t quite do what is required for real deployment, and that gives you research challenges again.”

Imperial enjoys collaborations with major firms such as Rolls Royce and IBM that have been built up over decades, and Jennings admits that “established industries that have always worked with universities are easier” to make links with than companies in “newer areas that aren’t used to it”. Forming relationships with new companies means that “you have to go through some pain at the beginning to understand what everyone is after”. But this should not stop academics trying to find partnerships in untapped sectors, Jennings insists.

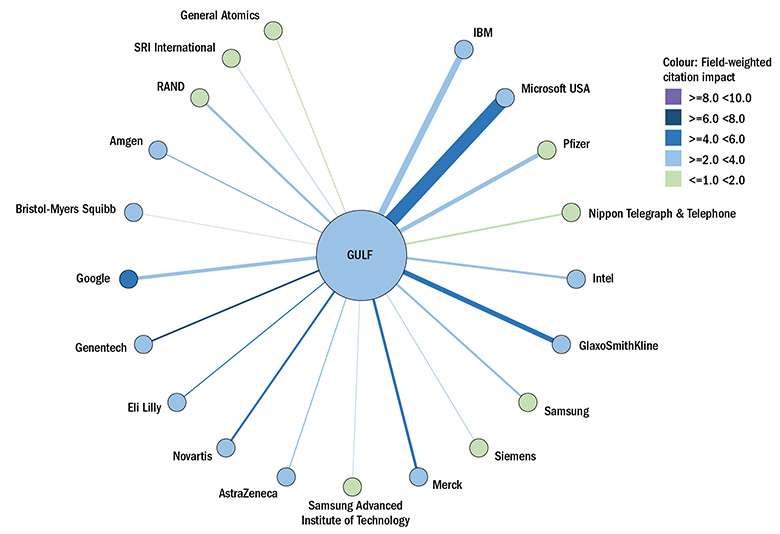

The Elsevier data on the GULF universities show that the bulk of collaborations are currently focused around fields such as life sciences and computing. The list of 20 companies that co-publish the most papers with academics is dominated by major IT firms such as Microsoft, IBM and Google and by large pharmaceutical companies such as GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer (see graphic below).

Good company: biggest industrial partnerships

GULF universities’ top 20 industrial collaborators

Node colour = institution FWCI

Node size = number of publications

Thickness of line = number of co-publications

Colour of line = collaboration FWCI

Source: Elsevier

It may simply be that this reflects the fact that drug discovery and emerging technology have the biggest potential for research commercialisation, but there may also be more complex reasons and trends driving this.

Adam Stoten, chief operating officer at Oxford University Innovation, which manages Oxford’s technology transfer activity, says that in the case of medical science there has been a shift in recent

years towards big pharma companies “downsizing their drug discovery capabilities and capacities”.

“What they are more focused on in-house is putting new drugs into clinical trials and then marketing and selling [them]; they are looking for smaller biotech firms and universities for the early-stage innovation.”

This has led to innovative new academic-industry relationships such as LAB282, an early-stage research collaboration worth more than £10 million between Oxford and the German drug development firm Evotec. Evotec contributes funding, expertise and technology to selected academic research projects that it believes might have future commercialisation potential. Oxford retains any intellectual property from its discoveries, but Evotec receives a stake in any company spun out of the research.

Stoten has also seen moves towards more open innovation models involving larger multinationals. His example is the Structural Genomics Consortium, which was started by the medical research charity Wellcome Trust but now has backing from a number of major pharmaceutical firms, such as Pfizer and Bayer. All the results from the research – into the three-dimensional structures of human proteins – are open access, but Stoten says that the firms can see the long-term potential of using the discoveries for later-stage commercial benefit.

“I think there is increased interest from companies within life sciences – but also other sectors – to look to universities as the source of new product ideas. There is certainly an earlier engagement. That is part of the bigger open innovation trend,” he says.

In information technology, open innovation and the sharing of discoveries is more established. Sandy Blyth, global managing director for the Outreach arm of Microsoft Research, drives the firm’s engagement with academia. He says that publishing openly was “a founding tenet” of the centre’s approach.

“Since our inception in 1992, we have been committed to disseminating our research and scholarship as widely as possible, as we recognise the benefits that accrue from that dissemination, including more thorough review, consideration and critique, and a broad increase in the scientific, scholarly and critical knowledge available,” he says.

Isabel Yang, vice-president of another long-standing tech collaborator with universities, IBM, also stresses that her firm “strongly encourages publications” and contributing to open-source software. “We believe that our work with universities should be as open as possible,” although she adds that “in situations where we think the IP should be protected, either the university or IBM would file for patent protection”.

But is this open science approach really the reason why the tech and life sciences sectors dominate collaboration with universities? Is it something that other sectors should mimic? Or is it more a case of the biggest firms and richest sectors being able to afford to carry out collaborative research? And is there also a risk that such firms might choose to work with only a narrow band of elite universities?

Thomas Hanke is head of academic partnerships at Evotec, and part of his time is currently spent at Oxford selecting the projects to take forward with LAB282. In his view, it is inevitable that companies will be attracted to certain research centres.

“There are gravitational forces where, once you’ve identified centres of excellence – like the golden triangle in the UK [Cambridge, Oxford and London], or the Boston area in the US, or the Bay Area [near San Francisco] – there is a [virtuous] circle where expertise, money and certain capabilities will come together and generate a critical mass, which will then attract additional funding and expertise,” Hanke says. “But I do also strongly believe that there are other places in the UK and in Europe where there is excellent science being done – and Evotec is open to new partnerships.”

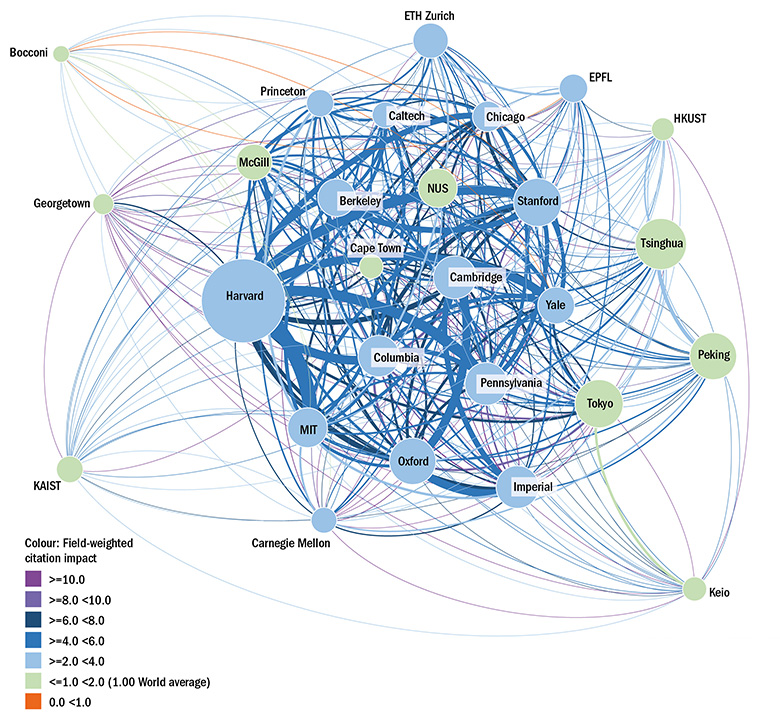

The Elsevier data also demonstrate that, as a group, the GULF universities have not only been mopping up a large share of industry collaborations but have also built up very strong research connections among themselves, too (see graphic below).

Neural networks: the strength of GULF university collaborations

Extent and citation impact of intra-GULF collaborations

Node colour = institution FWCI

Node size = number of publications

Thickness of line = number of co-publications

Colour of line = collaboration FWCI

Source: Elsevier

Elsevier’s Aisati says that he is fascinated by the fact that the network map of collaboration – in which the strength of universities’ co-publication links determine how closely they are placed to each other – still mirrors a geographical pattern to some extent.

“When you look at the universities in the centre, it is the institutions in the Western countries,” he points out, whereas the outliers are mainly those in Asia (Georgetown is an exception, perhaps because of the specific nature of its collaborations).

The impact of such inter-group collaboration on research citations is massive: the darker hue of the lines in the network map shows that the field-weighted citation impact of work co-authored by academics from the institutions is consistently high.

However, this raises the question about whether such networks of elite research universities are inadvertently draining research strength from other institutions and geographical areas, potentially weakening the potential for other universities to transform their regions economically.

Stoten says that although it is the reality that companies are often attracted to large institutions with a wide breadth of excellent research, there are smaller universities that “have some very, very productive, long-term, strategic relationships with corporate partners around a particularly specific area of science”. And Imperial’s Jennings adds that “geography is quite important” in many corporate relationships, with companies simply choosing to work with their nearest higher education institution.

The Elsevier data suggest that the strongest industry-academia links are confined to the West, and particularly the US and the UK. Evotec’s Hanke perceives “a greater openness to these kinds of collaborations in the UK than there currently seems to be in parts of continental Europe”, something he puts down partly to recent public funding pressures but primarily to a greater entrepreneurial spirit among academics in the country.

“In my experience, there is possibly less of that entrepreneurialism in countries such as France and Germany or Italy, where there is more of a closedness within the academic community,” he says.

Meanwhile, Jennings says that the developing world could benefit more from industry-academia links if the nature and scale of collaboration with such nations is changed by funding programmes such as the UK’s Global Challenges Research Fund – a five-year, £1.5 billion scheme aimed at addressing problems facing developing countries, partly through developing their own research capacities. “I think that will lead to very much different patterns and different sorts of impact,” Jennings predicts.

It is clear that the ability of universities in groups such as GULF to use their networks to broaden economic impact beyond the usual beneficiaries will be a key challenge for the future of knowledge transfer. And it follows that for economic growth to benefit more people and countries than it does now, it will be vital that this challenge is met.

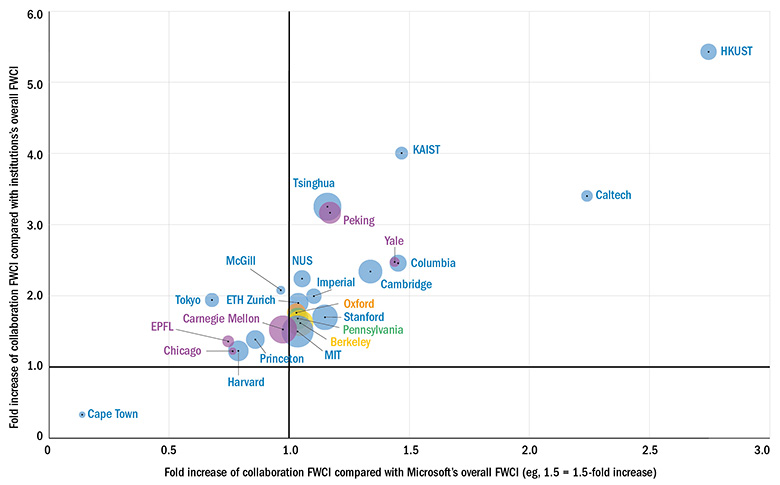

Citation impact: universities reap outsized rewards from collaborations

Circle size = number of co-authored publications

Source: Elsevier. Note: Colours have been used to clarify circles but do not signify data

The Elsevier data on the impact of academic-industry links within the Global University Leaders Forum show that the universities and the companies do not always reap the same rewards from working together, at least in terms of research impact.

For instance, those universities that work with Microsoft – which has the highest volume of collaboration with GULF universities – tend to benefit more than the Microsoft researchers do from co-authorship, in terms of its effect on the research’s field-weighted citation impact: a measure of citation impact that takes into account global and disciplinary averages.

The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology sees more than a fivefold increase in its FWCI when collaborating with the company, compared with the university’s overall figure, while the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST) chalks up a fourfold increase. The impact is smaller for other GULF universities, but most of them still gain more than Microsoft does, compared with the firm’s overall FWCI (which takes into account all the papers the firm published between 2012 and 2016, whether by itself or in collaboration with anyone else). Some of the GULF collaborations – including those with Princeton and Harvard universities – actually record a lower FWCI than the firm’s overall average.

Nevertheless, Sandy Blyth, global managing director for Outreach at Microsoft Research, is clear that “ultimately our customers and partners get a -better product or service” thanks to academic collaboration.

“Microsoft’s research is improved because our ideas are challenged, our scope is extended and our impact is magnified with the resources of leading universities and their students and faculty,” he says.

And Isabel Yang, vice‑president of another long-time academic collaborator, IBM, draws attention to the “obvious” benefit of university-company collaboration – “nurturing the next generation of talent that benefits not only IBM, but society as a whole”.

Simon Baker

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Pair bonds that pay

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?