The Covid-19 pandemic has tested the resilience of governments around the world. But as countries move out of immediate crisis mode and implement a science- and data-led containment and control strategy, the political agenda is shifting towards a focus on accountability and lesson-learning.

The multilevel nature of these scrutiny processes is reflected in the planning of several forthcoming inquiries. The Scottish Government has published a public consultation on the aims, process and objectives of a future Covid-focused public inquiry. The UK Government has committed to establishing an independent public inquiry next spring, and to announce its chair before Christmas. And the general assembly of the World Health Organisation, the World Health Assembly, has called on the WHO to conduct “an impartial, comprehensive, and independent evaluation” of “the experience gained and lessons learned from the WHO-coordinated international health response to Covid-19”.

The importance of using research to inform policymaking is now broadly established. This is especially true in the UK, where the research excellence framework incentivises non-academic impact and where specific investments and innovations – the What Works network and the Universities Policy Engagement Network being key examples – have created translational research infrastructure.

But the use of research evidence to inform the design and effectiveness of scrutiny structures themselves – although highlighted as a potential form of impact in REF guidance documents – is far trickier and rarely traversed terrain.

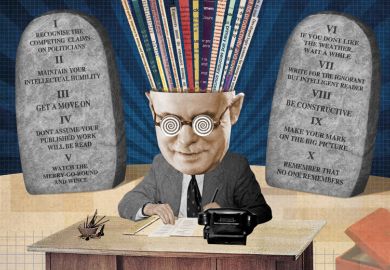

Accountability processes fulfil a range of roles. Arguably the two most important are, first, exploring what happened in relation to a specific event, challenge or crisis in order to allocate either credit or blame, and, second, drawing out the lessons that need to be learned in order to build future resilience. The issue is that although these dimensions are not mutually exclusive, the core insight from a vast seam of scholarship on public accountability is that a focus on blame too often squeezes out lesson-learning.

That is, to be “held to account” is associated not with a sensible or balanced review of the evidence on which decisions were taken – or with an appreciation of the contextual pressures under which ministers and their officials worked. Rather, it is associated – especially in press reporting – with a more brutal focus on blame and scapegoating. Hence, there is very little incentive for governments to request help in making scrutiny structures more effective.

A case in point is the UK Parliament’s recent joint committee report Coronavirus: lessons learned to date. What was striking about it was the degree to which it explicitly attempted to eschew a focus on blame for one focused on lesson-learning. That it nevertheless triggered a media storm of blame-based debate underlines the difficulties for any researcher seeking to inform effective scrutiny structures.

In many ways the creation of an independent public inquiry is intended to facilitate a more considered and balanced review of the evidence by creating a degree of space between the scrutiny process and day-to-day partisan politics. However, the evidence and research on public inquiries suggest that they are generally a highly ineffective means of learning lessons. Or, more precisely, the most effective inquiries in terms of lesson-learning and positive policy impact tend to be highly focused investigations.

The Covid inquiries are likely to be incredibly broad in scope, with overlap, duplication and boundary disputes between different bodies’ inquiries somewhat inevitable. But there is a significant opportunity here for the arts, humanities and social sciences to demonstrate professional agility and intellectual ambition.

The UK’s International Public Policy Observatory (IPPO) is seizing this opportunity by launching a novel design-orientated work stream on public inquiries. The key to IPPOs’ approach is to attempt to inject a choice-led and solution-focused perspective into the design of inquiries. The ambition is to stretch and challenge politicians and policymakers to acknowledge not only the existence of a far larger range of options in inquiry structure than is commonly recognised but also the political, economic and social benefits of innovating in the scrutiny space.

The key lies in corralling and presenting the existing research base on inquiry effectiveness to politicians and officials in a way that draws not only on interdisciplinary insights (from history to architecture, visual methods to cultural studies, design to ethnography) but also on an explicit understanding of the need to build and maintain high-trust, low-cost relationships between politicians and researchers when working within such political terrain.

The recent report by the Brazilian Senate into the country’s response to Covid – which called for the country’s president, Jair Bolsonaro, to face murder charges – underlines just how politically charged the atmosphere surrounding inquiries is likely to be. But as evidence grows of a global democratic recession then so too does the need for researchers to do all they can to ensure that scrutiny yields more examples of lesson-learning – and fewer “gotcha” headlines.

Matthew Flinders is professor of politics at the University of Sheffield and vice-president of the UK’s Political Studies Association.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?