One morning recently, as I drank my coffee, I read another call for papers on a conference session about geographies of decolonisation. In a caffeine-fuelled flash, I called for participation in an “expert” panel on decoloniality on Twitter: “Join me in the race to produce competitive, four-star and sole-authored articles about decolonialism in the cognitive dissonance edu-factory!”

I was thinking of all the conversations with frustrated anti-racist, Indigenous, feminist and queer fellow scholars and my colleagues of colour who invest their entire lives in decolonising their universities with their research and teaching.

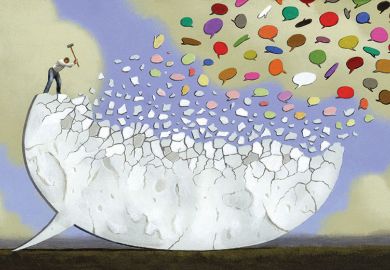

I thought of how these scholars engage in arts-based methods with artists and activists – for example Chicano performance artist William Franco, who described to me decolonial arts practice as a collective “chip, chip, chipping away” at hierarchical structures of knowing in order to build alternative worlds and sustainable futures.

Going by the onslaught of listserv posts, there appears to be an upsurge in creative and decolonial practices in my discipline of geography. But have we as scholars done enough to decolonise our own institutions?

As Richa Nagar, professor at the University of Minnesota, and Pat Noxolo, senior lecturer in human geography at the University of Birmingham, point out, geographers engaging in arts-based methodologies continue to prioritise Eurocentric and Anglo-American social theories while excluding “non-Western” inquiry and praxis.

Moreover, universities in the Global North continue to be very white, very heteropatriarchal and very colonial in their appointment of staff, as well as in the conceptual and methodological approaches they reproduce.

In this way, the higher education sector continues to reproduce the “cognitive dissonance” that Frantz Fanon critiqued decades ago. I think we all know of bureaucratic university initiatives that promote, manage and rank indicators for mental health, well-being, diversity and equity, yet still work to intensify workloads and stress. These initiatives are all part of a metric-driven audit and performance management culture that strengthens hierarchies and divisions.

In the UK, for example, feminist geographers have pointed out how research excellence framework rankings entrench race and gender hierarchies: men tend to cite men more often than women, and white scholars tend to cite other white scholars.

Critics also point out that this ranking regime risks favouring sole-authored articles over collectively produced work derived from arts-based and activist research.

Recent studies demonstrate how the REF is deepening inequalities as universities race to hire highly paid superstars to improve rankings while simultaneously exploiting precarious researchers, teachers, administrators and campus staff in a race to the bottom. How do we trust an upsurge of decolonialism in an accolade culture?

The tweet was also my response to the bizarre corporate culture that I have encountered while working in the university sector in the UK for the first time. In my time as a researcher here, senior administrators have used language like “pump priming” for our “research pipelines” that has shocked me.

Coming from unceded Secwepemc Territory in a place named British Columbia, Canada, I thought of the Tiny House warriors who are Indigenous water protectors fiercely fighting pipeline development. How would they respond to this language? Sarah de Leeuw at the University of Northern British Columbia and others accuse university research of implementing the same languages and logics that violently disrupted, and continue to disrupt, the lives and spaces of Indigenous people. These tools of settler colonialism are not buzzwords.

I’ve attended workshops where private sector consultants have offered tips on how to develop a social media brand and market my research like products. As Métis scholar and poet Zoe Todd contends, even well-meaning research produced within this context can result in “fraught and violent collateral damage” including roughshod ethics and a lack of trust among the communities that researchers are engaging with. How should I market my new decolonial toolkit to extract research?

As Eve Tuck at the University of Toronto and Wayne Yang at UC San Diego argue, within the current context decolonial theory gains popularity only as a metaphor, a myth that recentres Euro-white supremacy. Or, as a friend once said, this trend is about as sincere as a corporate responsibility initiative or a marketing gimmick.

However, as a white researcher working for a privileged university, I have to consider my accountability as part of this colonial system of knowledge and do more than fire off social media posts from my kitchen table.

For me, this includes continually reflecting on my complicity in colonial systems, and undertaking collective activism. To unsettle this, I have to unsettle myself. As scholars in Gurminder Bhambra, Kerem Nişancıoğlu and Dalia Gebrial’s recent book Decolonising the University contend, we cannot offload this work to scholars already marginalised by these violent systems.

There are some great examples of this in the work that Indigenous and non-Indigenous scholars are doing to walk the talk and make sure that decolonisation is more than a metaphor. Forging solidarities with activists, their work contests extractive industry development, colonial gentrification dynamics, precarious work across various sectors, the prison industrial complex, and the securitisation of urban spaces. Geographers are especially well-positioned to do this work given that questions of power, land and space are at its core.

And they are taking back this concept by nurturing what Zoe Todd refers to as “a culture of joyous and raucous co-celebration of the relationships which make our time here possible”, which may have been what I was trying to do with my tweet: feel someone else laugh and express their frustration with me. In this work we will make mistakes, try again, fail again. But we have no other choice but to keep chip, chip, chipping away.

Heather McLean is an Economic and Social Research Council fellow at the University of Glasgow.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?