Choosing your co-authors is not dissimilar to choosing a life partner (except you can always change your partner, but once your names are together on a paper, there’s no taking it back). Generally, academics team up with close colleagues or others from their field, but the literature also evidences some unexpected collaborations.

David Manuwal, an emeritus professor at the University of Washington, managed to get his wife, daughter and son involved in a paper, while American physicist Jack Hetherington famously added his cat as a collaborator.

Four (unrelated) Goodmans collaborated to produce a joke paper entitled “A few Goodmen: surname-sharing economist coauthors” and a whopping 284 authors sharing the name “Steve” contributed to a paper entitled “The morphology of Steve”. The paper was a by-product of the National Center for Science Education’s Project Steve, a comic riposte to creationist groups that had been assembling lists of “scientists who doubt Darwinism” to cast doubt on the theory of natural selection.

While 300 authors may seem unmanageable, even for a spoof study, the number of individuals supposedly contributing to academic papers is increasing exponentially. In 1963, Derek de Solla-Price predicted that by 1980 the single-author paper would become extinct. We are now well into the noughties and single-author articles persist, but we have witnessed unfettered growth in author numbers and the emergence of the era of hyperauthorship.

While anywhere between two and 10 authors is common, some papers take collaboration much further. Some examples:

- A paper on fruit fly genomics boasting more than 1,000 authors

- A 2016 paper in Autophagy with close to 2,500 authors (including 38 Wangs)

- A 2012 paper announcing the observation of the Higgs particle at the European Organisation for Nuclear Research (Cern) with 2,924 authors (the standard practice when citing such a paper is to cite the ATLAS Collaboration as the author – unlucky for Mr G. Aad of Aix-Marseille University, who would otherwise have been first in the list);

- A subsequent 2015 paper from Cern involving both research teams for the first time, resulting in 5,154 authors (the first nine pages contain substantive discussion of the findings; the following 24 are dedicated to listing the authors and their affiliations).

Aside from the serious questions about what "authorship” even means in such contexts, this is a colossal waste of paper (and/or disk space).

Another challenge is remembering the names of all the contributors. In one Nature paper, a research group overlooked no fewer than five authors, misspelled some names, and mixed up their funding sources. This error was picked up reasonably quickly, whereas it took two years for anybody to notice a couple of missing co-authors on a paper in Ecology Letters.

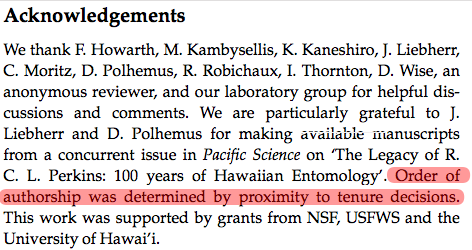

Whether you have two or 200 co-authors, the question of the order in which the names appear rears its ugly head. One 1989 paper applies a refreshing dose of pragmatism and honesty: “Order of authorship was determined by proximity to tenure decisions.” This is not unheard of. In one survey of 127 papers, four determined author order by proximity to tenure decisions.

Materials scientist Sylvain Deville has meticulously documented a host of unorthodox methods for determining author order. Randomisation is common, and at least 15 papers state that the order was decided by coin toss (they variously specify a two-pence coin, a weighted coin and a computer-simulated coin). One paper says that the coin toss took place “in an expensive restaurant”, while another, bearing the telltale signs of a sore loser, tells us that author order was determined “by a flip of what William B. Swann, Jr. claimed was a fair coin”.

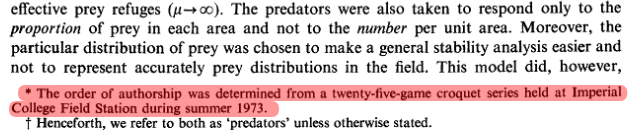

In their 1974 paper, Hassell and May state: “The order of authorship was determined from a twenty-five-game croquet series held at Imperial College Field Station.”

Not described in the paper are the somewhat underhand methods used to ensure victory, later elucidated by University of Oxford biologist Charles Godfray:

Croquet was played every lunchtime during May’s summer visits on a pitch customised by a large population of rabbits. Visitors were invited to play though inevitably lost due to the huge home-team advantage knowledge of the pitch’s precise topography afforded. Visitors also frequently declared themselves disadvantaged by the alleged tactic of being asked complex ecological questions mid-stroke. This was a different game from the traditional English vicarage-lawn contest!

Others have used less sophisticated methods: a tennis match; rock, paper, scissors; and even “a scramble competition for peat-flavoured spirit”.

So don’t forget to add all your co-authors, and next time the pesky question of author order arises, don’t settle for simple common sense – find a fun way to figure it out.

Croquet, anyone?

Glen Wright blogs about the hidden, silly side of higher education at Academia Obscura and tweets at @AcademiaObscura. The Academia Obscura book is available for pre-order now.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?