With Covid-19 still ravaging the US, Detroit once again epitomises the country’s structural inequalities. The combination of poverty, inadequate housing, a legacy of racial segregation and lack of access to healthcare leads directly to the underlying medical conditions (such as diabetes, heart and lung disease) that render so many inhabitants of America’s largest black-majority city particularly vulnerable to infection and death. If Mark Jay and Philip Conklin’s A People’s History of Detroit does not explicitly anticipate the current coronavirus crisis, it certainly explains the contours of its intense and rapid impact.

The authors situate their historical study within the context of the city’s regeneration in the wake of its 2013 municipal bankruptcy. This apparently glittering “comeback” was characterised by severe austerity measures, militarised policing and extensive public subsidisation of private developers such as Dan Gilbert. The chairman of a lending company that benefited from the subprime mortgage crisis of 2008, resulting in widespread dispossession of homes, Gilbert is considered a local “superhero” because of the scale of his investment. He in effect owns more than half of downtown Detroit, including many “abandoned” properties sold to him by the city for a dollar. The city, however, remains jobs-poor, with only about 200 jobs available for every 1,000 residents, and a weak public transport infrastructure. This, together with closure of schools, home foreclosures and water shut-offs – described by the We the People of Detroit Research Collective as “genocidal” – forces its poorest inhabitants to the margins of its increasingly gentrified core.

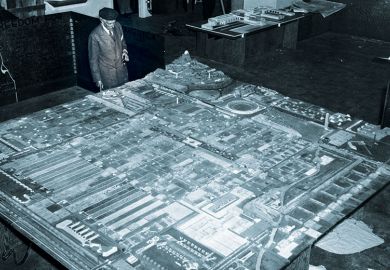

Jay and Conklin stress that this is not the case of two disparate cities existing simultaneously. Rather, Detroit is a co-constituted unity in which corporate revival is yoked to immiseration. The city is unevenly made and remade by profit-making at the direct expense of the working class, its precariously under- and unemployed. The book traces cyclical processes of urban “creative destruction” from the brutal “glory days” of the automotive industry in the early 20th century, through the Great Rebellion of 1967 (when 43 people were killed and more than 1,000 injured during confrontations between black residents and the local police force) to failed attempts at regeneration in the violent, hollowed-out, deindustrialised landscape of the 1970s. If Detroit’s resilience, its survivalist spirit and ability to hustle are often celebrated, this is because there has been no alternative in a political-economic system that continually reproduces crises.

The authors offer a straightforward Marxist critique of capitalism and privilege the welcome voices of Detroit thinkers and activists such as James and Grace Lee Boggs, who were themselves influenced by Marxism. Their text, which occasionally feels preachy, is not without missteps. An unnecessary parenthetical comment that 9/11 was likely “an inside job” is a case in point. It would also benefit from a more nuanced embrace of Roland Barthes’ concept of myth, not simply to refer to ideological narratives but the way these are coded and operate through popular culture. The cultural industries are more than the elite entertainments presented here. Some consideration of Detroit’s extraordinary artists and athletes – Aretha Franklin, Diana Ross, Eminem, Ron LeFlore, Joe Louis – would have complemented understandings of the mythologised dynamics of labour, place and class at the heart of this book.

Roberta Mock is professor of performance studies at the University of Plymouth.

A People’s History of Detroit

By Mark Jay and Philip Conklin

Duke University Press, 336pp, £21.99

ISBN 9781478008347

Published 1 May 2020

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?