Browse the full results of the World University Rankings 2024

A new metric tracking university-led patents has thrown the spotlight on institutions that possess a singular bent for innovation with commercial applications.

The industry pillar for Times Higher Education’s World University Rankings 2024 introduces a measure for how often a university’s research is cited in patents. This expands the pillar from previous years, when a single metric was used: industry income or income that universities received from industry as part of knowledge transfer.

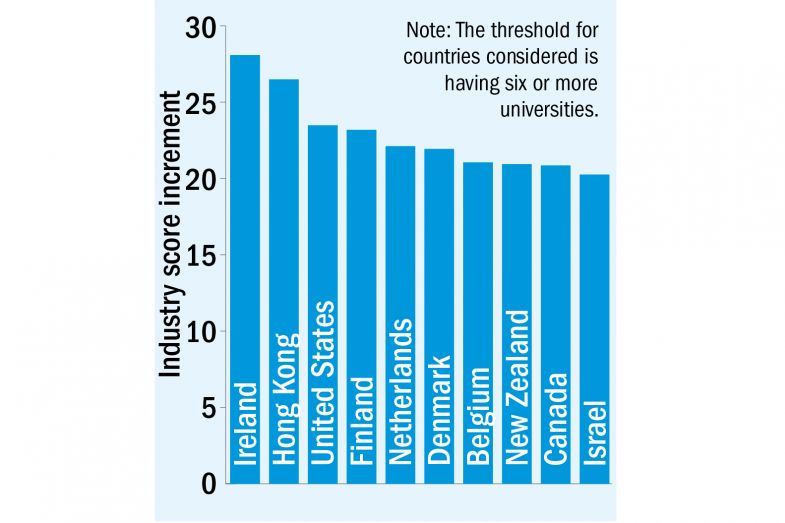

When considering countries with six or more universities, institutions in Ireland, Hong Kong and the US have seen the most improvement in industry pillar scores, indicating their strong performance on patents.

World University Rankings 2024: results announced

Irish institutions experienced the largest increase, with average industry scores jumping from 44.2 out of 100 last year to 72.3 this year.

Hong Kong’s universities chalked up the second-highest rise in scores, climbing from 64.9 to 91.4. The country’s institutions are also leading with the highest scores for the patent-specific metric, recording a near-perfect score of 99.7 out of 100. On patents, the Netherlands was close behind, scoring 99.5.

Top 10 countries for improvement in industry scores between 2023 and 2024

A total of 112 universities received top marks, 100 points, on the patent metric. Among these standout performers is Israel’s Tel Aviv University.

The university has its own technology transfer company, Ramot. It provides professional support to researchers, dealing with intellectual property and commercial aspects of research. Since its inception in the 1970s, Ramot has processed more than 5,000 patent applications; it holds a portfolio of approximately 1,600 patent applications and patents.

In recent years, the company has transitioned from just an outlet helping researchers dot the i’s and cross the t’s on patent paperwork to become a more proactive matchmaker seeking to create fruitful collaborations between industry and interested researchers.

Ramot approaches companies and asks them for a “dream wish list” of technology solutions that they would like to develop or real-world problems they want to solve, says its chief executive, Keren Primor Cohen.

The wish list is then circulated among researchers at Tel Aviv University. When Ramot connects an interested researcher with a company, they plan a joint research project and seek funding – either from the company involved or the government.

Cohen says Israel’s government “understands” the need for money to bridge the gap between early-stage technology and industry applications.

“The government thinks that there’s a lot of gold in academic institutions. And this gold needs to be dug out,” she says.

Government support, Cohen explains, carries technology to a more developed stage, lowering the risk for private investors. These investors step in at later stages and take the innovation to market.

But the process of obtaining patents also involves timing.

“When researchers come to us with inventions, most of the time, it’s very early,” Cohen says. If a patent application is filed prematurely, it might fail.

And while Ramot brings commercial expertise to the research process, being a university company means that it prioritises academic freedom.

This becomes crucial when companies collaborating with Tel Aviv researchers ask for work to be kept confidential and for publication to be delayed until its suits company interests.

“The company can say [to the researcher], ‘You will show me the results, and I will tell you if you can publish or not.’ This is not something that we can accept as a university,” Cohen says.

To protect researchers’ academic freedom, Ramot often includes specific conditions in their agreements with industry. For example, it may stipulate that the researcher will send research results to the company 30 days in advance of any intended publication, giving it time to consider a patent. After this point, the researcher is free to publish.

To their credit, Israeli institutions are unafraid that academics establishing start-ups might compromise their research quality – a stance Cohen supports.

“They believe that the more the merrier and that there’s a lot to be learned from the industry,” she says. “Giving the industry [a] place within the academic setting is a good thing.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?