For decades, Hong Kong’s universities occupied a distinctive place in global higher education: English-medium, outward-looking and institutionally closer in structure and ethos to the UK than to mainland China. They were ranked as among the most international universities in the world, and their campuses were widely seen as academic bridges between East and West, where students and scholars could work within China’s orbit without being subject to its restrictions.

However, that bridge began to look shaky when Hong Kong’s National Security Law was passed in 2020 in response to widespread student-led demonstrations advocating greater democracy in a territory that passed from British to Chinese jurisdiction in 1997 but which still operated separate political, legal and higher education systems. The law, imposed by Beijing, obliges authorities to detain people deemed a threat to law and order or political stability and has been used to prosecute student leaders and other advocates of democracy, such as newspaper mogul Jimmy Lai.

The law was widely depicted internationally as the death knell for free speech and institutional autonomy in Hong Kong, and large numbers of residents left the city, including academics and students. Many observers concluded that the region’s era as a genuinely international academic hub was drawing to a close.

Yet nearly six years on, university leaders in Hong Kong insist a different story is unfolding. They point to rising non-local enrolments, expanding exchange programmes and continued English-medium teaching as evidence that the system remains open. And rather than pushing back, the Hong Kong government is encouraging expansion, doubling the proportion of their student bodies that universities may recruit internationally in the 2024-25 academic year to 40 per cent and pledging to raise it again to 50 per cent from 2026-27.

Even before the doubling of the cap, in the 2023-24 academic year, nearly 75,000 non-local students, from more than 100 countries/regions, were studying post-secondary programmes in Hong Kong, according to a government source, and the trajectory was upwards. On courses funded by the territory’s University Grants Committee, for instance, there were just over 23,000 international students in 2023-24 – up from just over 19,000 in 2019-20, a 20 per cent rise.

The question, then, is not whether Hong Kong wants to internationalise, but how far that ambition can realistically go, what internationalisation means and who it ultimately benefits.

At the Hong Kong Polytechnic University, international exposure is framed as something every student will experience directly. The institution’s president, Jin-Guang Teng, said: “Every student should have one non-local study opportunity.”

He said the university planned to realise that ambition “in the next few years” by doing two things. “Up to half” of the university’s annual intake of more than 5,000 students will be sent on exchange programmes outside Hong Kong, and “about half” of the students will be required to do their compulsory three-credit “service learning” outside Hong Kong.

But not all non-local experiences will involve leaving China. “Among those who go out, ideally about half of them should go to a foreign country,” Teng said. “The other half should go to the Chinese mainland because our students need to not only understand the international landscape, but also our own national landscape.”

Many of Hong Kong’s international admissions also come from China. This year, PolyU admitted more than 1,100 non-local undergraduate students, with more than 400 from countries other than China, according to Teng. And, while Hong Kong’s vice-chancellors often stress a commitment to balanced international intakes, the reality is that students from the Chinese mainland make up by far the largest cohort, particularly at master’s level, as Teng acknowledged.

At Hong Kong’s eight public universities, Chinese students account for about 75 per cent of first-year non-local undergraduates in the 2024-25 academic year, according to figures obtained by the South China Morning Post from Hong Kong’s University Grants Committee. The newspaper also learned that 5,582 non-local, first-year students were admitted by the city’s eight universities, a 48 per cent increase from the year before, with the proportion of mainland students among them increasing by 55 per cent.

That trajectory is borne out by publicly available figures on UGC-funded programmes. These enrol lower proportions of international students – 18 per cent of undergraduates in 2024-25 – but that is up from 12 per cent in 2015-16 and amounts to a 77 per cent increase in total numbers. Over the same period, local undergraduate numbers have risen only 6 per cent.

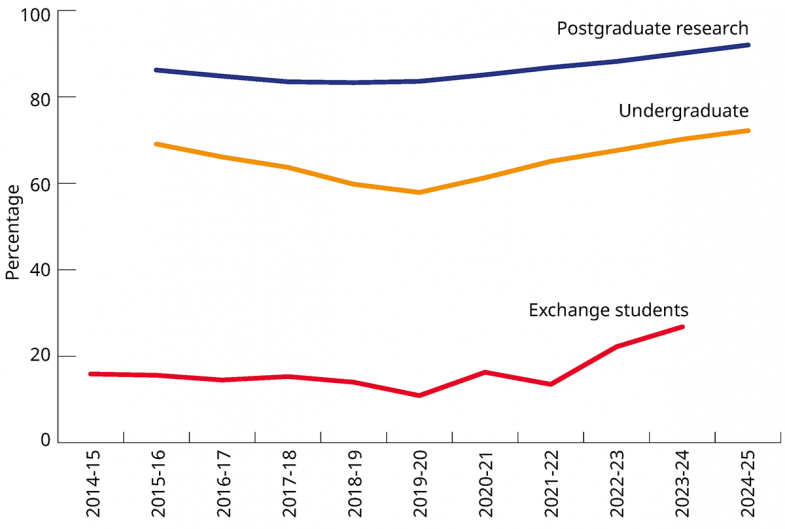

Chinese students as a proportion of international students on UGC-funded programmes

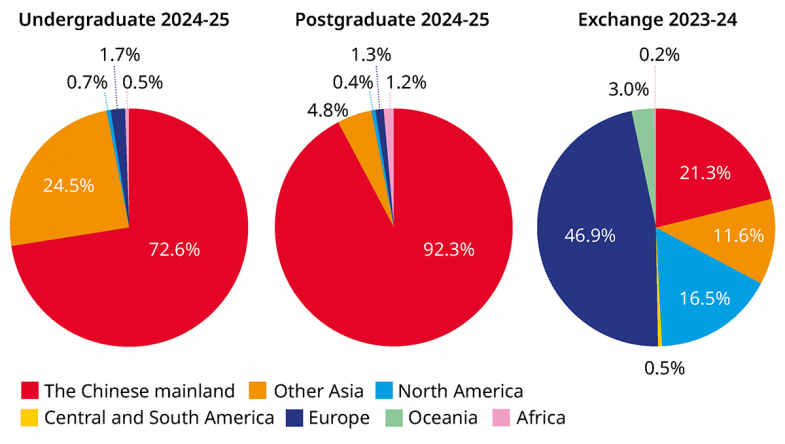

Meanwhile, the proportion of Chinese students among all international students has risen from 69 to 72 per cent. The rest are mostly made up of students from elsewhere in Asia (24 per cent in 2024-25), with only tiny handfuls from Europe (1.7 per cent) and North America (0.7 per cent).

The number of international students on UGC-funded master’s programmes is very low, but among research postgraduates, international students are particularly prominent, making up 87 per cent of the total in 2024-25 – up from 80 per cent a decade earlier and 57 per cent in overall numerical terms. And Chinese dominance is even higher, rising from 86 to 92 per cent of total international enrolment over the decade.

Interestingly, however, the regional proportions are very different when it comes to exchange and visiting students. Official figures reveal that mainland Chinese students only made up 21 per cent of students on UGC-funded programmes in 2023-24, while Europeans made up 47 per cent. But the Chinese proportion is up from 13 per cent in 2015-16 and has risen particularly sharply since 2021-22.

Source regions for international students on UGC-funded programmes

Vice-chancellors insist that Hong Kong remains attractive to all international students. For instance, Alexander Wai, president and vice-chancellor at the Hong Kong Baptist University, described Hong Kong as “a very metropolitan modern city. It’s very safe, the food is very good, you have access to the Chinese mainland if you want to learn more about China, which is almost as important as the US in terms of its economic and technology power.”

But language is one issue that international students face. While English dominates teaching, campus signage and marketing materials, Cantonese and Mandarin are far more commonly heard in corridors, cafeterias and common areas. One Western exchange student studying economics at the University of Hong Kong (HKU), who asked not to be named, said that while lecturers generally made an effort to teach in English, interaction between students often took place in other languages. “Chatting between a group of mainland or Hong Kong students will normally be done in Mandarin or Cantonese in most modules, but the lecturers will tend to stick to English, and when questions are put to the class they’re almost always in English, in my experience.”

PolyU’s Teng agreed that although English is the official language of instruction on campus, “local people commonly speak Cantonese to each other. Mainland students normally speak Mandarin to each other”. But he insisted that students from the Chinese mainland, too, are drawn by Hong Kong’s English-medium environment, as well as its “different educational experience”, and there are very few PolyU courses that aren’t in English: “We have a new programme called the master of technology entrepreneurship. This one will be delivered mainly in Mandarin supplemented with English, but almost all of our other programmes are taught in English.”

Joshua Mok, professor of comparative policy at the private Hang Seng University of Hong Kong, said that although his institution’s medium of instruction was English, “we are very accommodative. If students don’t understand, sometimes you allow them to explain in Mandarin and then translate. Education is about engagement.” That accommodation, he said, was intended to support participation, though he conceded that it could also reinforce “language clustering” in mixed classrooms, particularly when one group dominates numerically.

That is not a problem at Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, according to its vice-president for research and development, Tim Kwang Ting Cheng. “All courses are English, period,” he said. And that is a practical necessity: “In the classroom you have students not speaking Mandarin, you have students not speaking Cantonese. In order to deliver courses, only English works. We want to make sure we are not discriminating [against] any student.”

But the Western HKU student did feel excluded in some scenarios, noting that the common use of Mandarin and Cantonese “definitely makes it harder to form groups for group projects because [students] always try and get in a group with people speaking their language…In my Chinese mythology class, we were required to have Chinese-speaking students in each group and they would usually speak Chinese to each other, which made it hard to follow discussions sometimes.”

Outside the classroom, too, the student said integration was limited by language and institutional practices: “The language barrier is the big one: it makes joining in when people are in the common areas chatting and playing games quite intimidating and then that leads to different social circles forming.” Student societies pose similar challenges: “My friends who play sports say that most coaching and organisation is done in Chinese and then they will try and get a student who is better at English to translate for them, but they still say they’re left clueless half the time.”

Some social activities are even explicitly closed off to non-local students: “There’s also a lot of hall events that are locals only – even when they’re on my floor.” The student was “politely asked to leave my room for the evening” when the local students needed the room for a party.

And basic administration can also be difficult because “the people in the hall office and receptionists don’t speak English very well, so if I wanted to speak to someone, I’d need to book something in with someone who was more comfortable [in English],” the student said.

Those challenges are compounded by geography. As student numbers rise in the densely populated territory, accommodation has increasingly been pushed to the Northern Metropolis area, placing students far from campus and therefore limiting their ability to interact with other students there, such as over shared meals or in student societies.

Teng acknowledged shortcomings and said PolyU is taking steps to address them. “We have some student hostels or residential colleges where students from different places stay together,” he said. “Normally, in many of the hostels, they should speak English for their activities, so, there, students from different places can mingle well. On campus, of course, there are student societies and they should all use English to facilitate the participation of students from different places. [But] we don’t have a rule to say you must use English.”

In addition, PolyU has established a “global student hub: it’s a new space we created that was purposely built for mixing local and non-local students. So we are making some concerted efforts. But we can do more,” Teng said.

Yet language is only one part of the internationalisation equation. The US academic Gerard Postiglione, an emeritus professor at the University of Hong Kong, said that whether Hong Kong can function as a genuinely global education hub depends on how its universities are read internationally. “To become a global education hub, you will be successful partially on the basis of how the rest of the world perceives your universities’ institutional autonomy and professional academic freedom,” he said. And, in that sense, the National Security Law is a potential problem.

That said, he noted, perspectives will differ. “Who would expect Hong Kong or Singapore or even Japan or South Korea to be as academically free as the United States?” he asked. Hence, Hong Kong can feel open to scholars working within Asia, while raising hesitation among academics trained or based in the US.

The Western student THE spoke to said that when deciding whether to come to Hong Kong, they weren’t “overly worried because I didn’t think [the authorities] would be that worried about undergrads on exchange for a few months, especially in economics, and I think that’s largely been proven right.”

Indeed, Teng said that if people properly “understand Hong Kong well, they will find [it] to be a very safe, friendly and prosperous place, where the East meets the West...If they want to know Hong Kong better, they can come to visit...and see it for themselves firsthand. That’s my advice.”

But the student said there were subtle signals that shaped how issues were discussed: “Modules on Hong Kong that I have taken seem to teach and award marks based on repeating government buzzwords without really engaging too much with the issue of whether it is true.” And the absence of visible student politics also stood out. For instance, HKU’s “Democracy wall”, to which students and academics had previously pinned their political thoughts, “has been empty almost the whole time I have been here, which is definitely a reminder of where we are when I walk through campus”.

At both undergraduate and research postgraduate level, Chinese students’ dominance of international cohorts on UGC-funded programmes has accelerated particularly markedly since 2020, while all other regions have seen proportional declines even as total numbers have held steady. But it is important to keep in mind that this could also be a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, which began that year.

As for overseas academics, there has been no major exodus, universities insist. Benjamin Meunier, librarian at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, said Hong Kong universities remain highly cosmopolitan. “Academics have been educated overseas, so it feels like a very cosmopolitan community and there’s a lot of effort to celebrate diversity on campus.” But he cautioned that maintaining that uniqueness matters. “It’s important for Hong Kong universities to maintain that distinctiveness and not be exactly the same as universities that don’t benefit from the special administrative region status.”

Hong Kong’s increasing ties with China are illustrated by the recent establishment of several branch campuses in China by Hong Kong universities. Pawel Charasz, assistant professor in the School of Humanities and Social Science at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, has experienced “no constraints whatsoever” on his work, either in Hong Kong or the mainland. But while his research is on comparative politics and political economy, he doesn’t “work on topics that are particularly sensitive in China”. And since CUHK Shenzhen operates in English, it feels “a little bit shielded from the kind of government scrutiny that regular public universities get”. Moreover, he fears that “many people” probably decide not to come to Hong Kong in the first place owing to fears that their freedom will be restricted.

It may also be that that self-selecting factor means that as the proportion of students from the mainland continues to rise in Hong Kong universities, issues around English use and academic freedom escalate – further narrowing the diversity of the territory’s international student cohort even as its size in terms of raw numbers expands.

HKUST’s Cheng said his university will continue to maintain a balance in its international recruitment: “With the 50 per cent non-local cap, we allocate at least half for international, half for mainland students. That’s a typical composition,” he said. But, for other institutions, that kind of balance appears out of reach, and when the raising of the cap to 50 per cent was announced last October, William Yat Wai Lo, professor of education at Durham University, told THE that the move was “clearly aimed at attracting [more] students from mainland China”.

If that is so, it raises the question of what the Hong Kong authorities want from internationalisation. For his part, Postiglione cautioned against treating internationalisation as a purely numerical exercise: for him, its chief virtue is its contribution to teaching and learning: “Education in universities improves with the diversity of its students, including their cultural diversity, the ways that they communicate, their different thinking styles, and their career trajectories, local, national and international,” he said.

The challenge for Hong Kong’s universities, then, will be to deepen internationalisation without quietly narrowing its meaning and its purpose.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?