Browse the THE World Reputation Rankings 2020 results

Universities that are still building their global prestige are often perceived very differently in terms of discipline expertise at home and abroad, according to an analysis of Times Higher Education data.

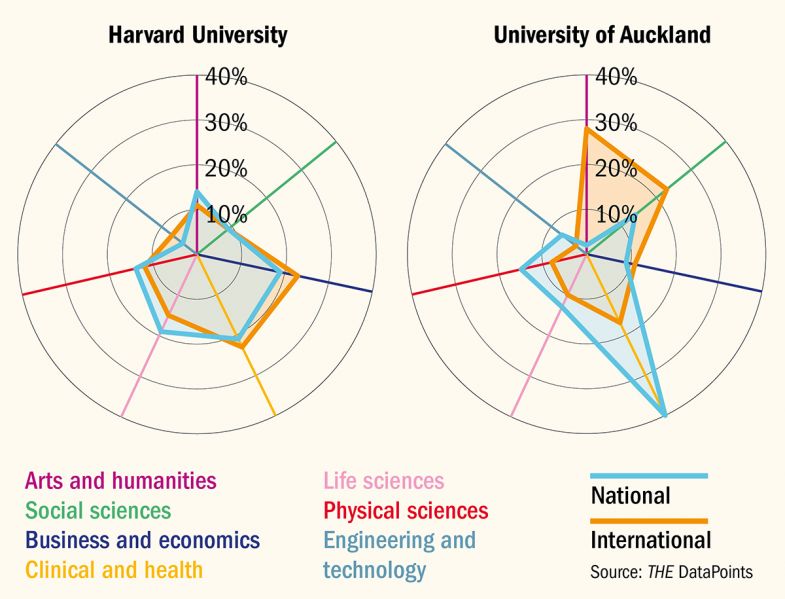

Analysis of the THE World Reputation Rankings 2020, which is based on a global survey of leading scholars, shows that the perception of performance by discipline for “superbrand” institutions, such as Harvard University and the University of Oxford, is very similar domestically and internationally. The universities receive a spread of votes from experts in all subjects, and there is no substantial difference in the distribution of those votes between domestic and international academics.

However, the expansion of the table this year to include 200 universities, up from 100 in previous versions, reveals that the distribution of votes for many of the new entries is substantially different depending on the location of the scholar, according to the analysis from THE’s data team.

For instance, the University of Oslo, which is ranked in the 126-150 band, receives most of its domestic votes from academics in the physical and life sciences, but the majority of its international votes come from scholars in the arts and social sciences.

Harvard v Auckland: a snapshot of two universities

A similar trend occurs for the University of Auckland, which makes its debut in the 176-200 band. The institution’s domestic votes are driven by clinical and health experts, but its international votes come largely from the arts and social sciences.

Meanwhile, Lomonosov Moscow State University, which has ranked in the top 100 of the reputation table since 2015 but, at 37th place, is not one of the “superbrand” universities, receives an even spread of votes by discipline among domestic academics. However, the bulk of its international votes come from scholars in the physical sciences.

The findings, which were presented at the THE Leadership & Management Summit, may suggest that more emerging universities in the global higher education sphere tend to focus initially on driving their prestige in one or two areas before building up a broader reputation.

Another explanation for the trend in Oslo and Auckland, according to Hans de Wit, director of the Center for International Higher Education at Boston College, is that scholars in STEM fields are more likely to vote for institutions in their own country, while those in the arts and social sciences are more willing to acknowledge universities abroad. Professor de Wit said this could be related to the fierce competition within the sciences.

“I think that scholars are a mix of honest academics and calculating national individuals,” he said. “If they have to assess the top universities, they have no problem to focus on the first dimension, as they are not in a competing environment. For the next level in the STEM fields, the competition is the highest and most relevant, so international scholars likely will be less supportive to their competitors abroad as that would reduce their chances in the rankings.”

In the case of Lomonosov Moscow State, Professor de Wit added, the reputation of physics at that institution and in Russia more broadly is “high enough” for it to receive acknowledgement, despite the competition.

Svein Stølen, rector of the University of Oslo, said national discussions of academia and research in Norway, as in many other countries, are dominated by science and medicine. This might mean that scientists in these nations have a stronger awareness of the top local universities in their fields than arts and social science scholars, he suggested.

“At meetings with my colleagues in Norway, I often have to be the person who promotes social sciences and humanities. But when I meet with the Guild of European Research-Intensive Universities, for example, I seldom have to be the person who speaks up for social sciences and humanities because others understand this as well,” he said.

Professor Stølen added that his institution is ranked as one of the best universities in Europe for social sciences and humanities “so, for universities outside Norway, this might be more visible than inside Norway, where the discussion is often about STEM”.

A spokeswoman at the University of Auckland said the institution’s large number of local votes from clinical and health scholars reflects the fact that its Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, along with its Liggins Institute, which focuses on fetal and child health, are leading centres for clinical and health research in New Zealand and have “strong research collaborations with the local district health boards and clinicians”.

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Distance shifts perceptions of strong fields

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?