British higher education enjoys a substantial "brain gain" in a global academic market that is increasingly dominated by young researchers, a report has concluded.

The Higher Education Policy Institute report explodes the enduring myth, originating from reports in the 1960s, that the UK suffers from an academic brain drain. In fact, the UK is a net importer of academics and is particularly good at attracting the most talented and highly cited people.

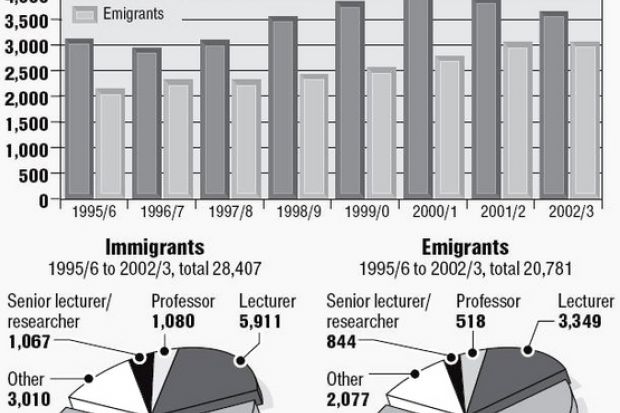

On average, between 1995-96 and 2002-03, for every ten academics who left the UK to work abroad 14 arrived from overseas, the Hepi report says.

Many of those arriving in the UK were British researchers returning after a period of working abroad, which they had used as a springboard for their career.

The report, the first of its kind in a decade, says that migration to and from the UK is "overwhelmingly a phenomenon affecting junior staff".

Staff on researcher grades account for roughly two thirds of migration in both directions. Only about 20 per cent are lecturers and 4 per cent senior lecturers. Professors account for 4 per cent of academic immigrants to the UK and 2 per cent of emigrants.

According to the report, UK higher education gains significantly by attracting more established and highly cited academics than it loses.

It says that while the UK loses more people in the early stages of their careers, "it attracts more people than it loses at later stages in their careers when they have built up research reputations".

Career development was the most commonly cited reason for migration - 80 per cent of those surveyed said their careers had been "strongly improved" as a result. This view was most common among UK researchers.

"These findings reinforce the point that among UK staff most mobility is among young researchers, often before they have embarked on a research career, and that for the great majority these periods employed abroad should not be regarded so much as emigration as career development," the report says.

The report pulls together evidence from two commissioned studies of the publications records of academics, the careers of "academicians" (fellows of learned societies such as the British Academy and the Royal Society), along with an analysis of Higher Education Statistics Agency data on staff movements, a survey of academic migrants and interviews with senior representatives of universities and learned societies.

Evidence gathered for Hepi shows that the US is still the most important destination for and source of overseas academics. But the net flow of migration is from the US to the UK, even though the US is the most popular destination for more experienced staff.

According to the data, other European Union countries may be gaining ground on the US as a preferred destination for UK staff. The data also show that young European researchers may be beginning to view the UK - rather than the US-as the best country in which to establish their academic reputations.

The report found that academic mobility is concentrated in disciplines associated with high levels of grant funding. In 2002-03, 37 per cent of immigrants and 41 per cent of emigrants were in the biological, mathematical and physical sciences.

Immigration is concentrated in the research-strong universities. Four such institutions - Oxford, Cambridge, Imperial College London and Nottingham - were responsible for employing nearly a third of academic immigrants in 2002-03.

tony.tysome@thes.co.uk </a>

Although a move abroad is essential for career development, you can always return home

The European researcher

The prospect of working in the UK's higher education system looked attractive to Denis Besnard as he grappled with the bureaucracy of trying to secure a research position at home in France.

He had gained a PhD in psychology from Provence University, but found he was considered "too junior", with not enough publications to his name, to qualify for the jobs he was interested in.

Then a colleague told him about a research position that had opened up at Newcastle University, in an area he was interested in - the interaction between computers and humans.

Dr Besnard said: "What I did not realise at the time was how relatively easy it is to be hired in the UK higher education system. That is not the case in France, where you have to go though a lot of red tape and you have to prepare a plan for your research.

"Because research projects in the UK are usually for a short period, institutions have to find researchers quickly and efficiently," he said.

"It means there are many more research opportunities in this country," he added.

The young Briton looking overseas

A period of working overseas is now a "must have" for career-minded young academics, according to Neil Sheppard, a DPhil student in his final year at Oxford University.

"For people in my position, who have done a science DPhil, it is virtually essential to continue your career by going to another institution, preferably abroad, because it shows that you are flexible and have had a broad experience.

"It is not only good for your career, it is good for your personal development," Mr Sheppard said.

Most young researchers want to go to the US, but Mr Sheppard, who is conducting research into HIV vaccines, hopes to find a post in Sweden.

"It has the highest percentage of gross domestic product investment in research and development in the world, and it is home to one of the world's biggest biotechnology parks, which is good if you want to go into more industrial work."

He is keeping an open mind about whether he will return to the UK once he has some experience and publications under his belt.

The academic returner

Molly Stevens, reader in regenerative medicine and nanotechnology at Imperial College London, is sure her career has been boosted by the four years she spent as a postdoctoral associate in the US.

Dr Stevens joined a research team at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2000 after being awarded a PhD in biophysical investigation from Nottingham University.

She said that the experience and the confidence she had gained from her time at MIT meant she was able to "hit the ground running" when she returned to the UK, and she was taken on as a lecturer by Imperial last year.

"Coming back here, I felt I was more than happy to jump into an academic position and, within a year and a half, I am making quick progress," Dr Stevens said.

She said she wanted to see what academic life was like in theUS and to experience a different research environment.

"It is very different in the US. Postdocs can get freedom and independence of the kind you only get once you reach lecturer grade in the UK."

Dr Stevens said that the contacts made abroad are very useful for a researcher returning to the UK, as they can lead to research collaboration and visiting positions that might not otherwise be open.

"It is very beneficial whether you decide to stay or return to the UK. You learn an awful lot, and I would recommend it to anyone."

Source: Hepi

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?