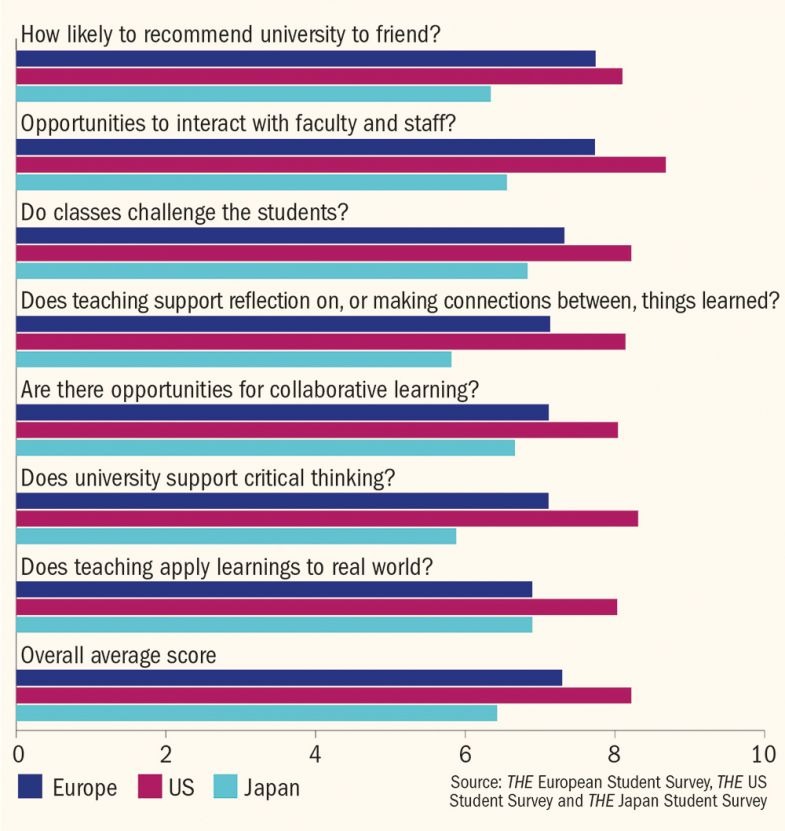

A cursory glance at the results of Times Higher Education’s surveys of students in the US, Europe and Japan reveal major regional differences in how those at university rate their higher education experience.

Students in the US, for example, give an average score of 8.2 out of 10 in the survey, which asks them to rate elements such as their opportunities for collaborative learning and whether they feel challenged by their classes, while those in Japan are much more critical, providing an average score of 6.4 based on the same set of questions. Students in Europe sit in the middle with an average score of 7.3 out of 10.

But looking beyond these headline findings, the data also reveal the varying perceived strengths and weaknesses of the different higher education systems.

Students in Europe and the US, for instance, generally give a high score when it comes to their opportunities to interact with faculty and staff, but they rate their universities much more poorly on whether the teaching applies their learnings to the “real world”.

In contrast, Japanese students give their highest average score for this latter measure, but provide their lowest scores for how their university supports critical thinking and reflection on, or making connections between, things learned.

US beats Europe and Japan in student satisfaction survey

The analysis was based on responses to the seven questions that were asked in the latest editions of the THE European Student Survey, the THE US Student Survey and the THE Japan Student Survey. The surveys were completed by about 170,000 students in the US, 125,000 in Europe and 37,000 in Japan.

Anne Colby, adjunct professor at Stanford University’s Graduate School of Education and co-author of the 2013 book Rethinking Undergraduate Business Education, said the US findings matched previous research showing that “US universities tend to do pretty well in offering seminars, opportunities to interact with faculty and academic advisers outside class, and collaborative student projects”.

However, she said, “practical reasoning – the capacity to draw on knowledge and intellectual skills to engage concretely with the world and to decide on the best course of action within a particular situation” and “the reflective exploration of meaning – understanding the implications of academic learning for who I am and how I engage with the world” were two areas that have been “relatively neglected” in US undergraduate education, especially in vocational majors such as business.

Professor Colby added that her current research showed the importance of the development of purpose in undergraduate students for cultivating their ability to apply their lessons to the world, with purpose defined as “a sustained active commitment to goals that are meaningful to the self and aim to contribute beyond the self”.

Students with high purpose scores tend to speak to faculty and other staff about “connecting my strengths with what the world needs” and report growth on measures such as “understanding problems facing my community” and “solving complex real-world problems”, she said.

Kiyomi Horiuchi, research associate at Hiroshima University’s Research Institute for Higher Education, said Japanese students’ relatively high levels of satisfaction with the real-world application of what they have learned could be related to the growth in practical and professional fields of study, such as nursing and occupational therapy, in the country’s universities.

Such subjects “have been popular among high school students and their parents” because there is a higher chance of future employment and “for students learning under these professional departments, it would be easier to imagine applying their learnings to the real world”, he said.

Meanwhile, Japan’s relatively low scores on critical thinking and making connections between things learned could be explained by the country’s focus on the “one-way lecture” from primary to higher education, as well as the fact that there is little cooperation between individual departments at universities, according to Mr Horiuchi.

Although the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology is urging universities to provide more “active learning” style classes and to become more interdisciplinary, Mr Horiuchi predicted that the transition would take time.

“University entrance examinations, as well as regular exams conducted at high school, usually ask simply what students learned from the textbooks and lectures; students tend to satisfy [this] by just absorbing the knowledge from taking courses,” he said.

Mr Horiuchi suggested that introducing later subject specialisation and more flexible curricula that enable students to undertake courses outside their own departments could help to address the perceived weaknesses.

But Thomas Brotherhood, a PhD student at the University of Oxford and the Centre for Global Higher Education, who has researched in both the UK and Japan, said “students may not be as quick to welcome a more active learning style as you might expect”.

“After the challenges of their university entrance exams, many students welcome a more relaxed learning style and the freer social environment of university,” he said.

“Students may not feel overly challenged by their education at the minute, but I’d guard against changing this overnight and upending the expectations of various stakeholders in a university education: students, faculty, employers.”

Mr Brotherhood added that Japan’s relatively low scores in the engagement survey could relate to the fact that companies preferred to hire “a blank slate, who can be moulded according to the needs of the employer”.

“Of course, technical knowledge is appreciated in certain fields, but typically high-level skills and critical thinking are valued beneath adaptability to the systems and requirements of the specific employer. Students are aware of this and realise that the reputation of their university is more valuable than what they study or how they study it,” he said.

Mr Brotherhood concluded that “just because levels of individual satisfaction with university education” in Japan are not as high as in Europe and the US, he would “guard against concluding that [higher education] isn't playing equally important social roles, and performing them equally well”.

“Offering a respite from ‘examination hell’, giving [students] an opportunity to engage in more societies, and providing an education environment that is essentially matching the expectation of both students and future employers – these are all important,” he said.

ellie.bothwell@timeshighereducation.com

Methodology

The analysis is based on students’ responses to seven questions (on a scale of 0 to 10):

- to what extent does the student’s university support critical thinking?

- to what extent does the teaching support reflection on, or making connections between, the things that the student has learned?

- to what extent does the teaching support applying the student’s learning to the real world?

- to what extent does the student have the opportunity to interact with faculty and teachers?

- to what extent does the university provide opportunities for collaborative learning?

- to what extent do the classes taken challenge the student?

- if a friend or family member were considering going to university, based on your experience, how likely or unlikely are you to recommend your university to them?

The THE European Student Survey was conducted online in partnership with market research provider Streetbees. It collected the views of more than 125,000 university students across 18 European countries.

The THE US Student Survey received more than 170,000 responses. Respondents were recruited by Streetbees and by universities that distributed the survey to random samples of their own students.

Responses to the THE Japan Student Survey were collected through promotion by education company Benesse and self-distribution by participating institutions. Overall, almost 37,000 students from more than 400 Japanese universities responded.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Just watching or truly engaged? How students compare internationally

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?