Almost 300 years ago, a physicist named Laura Bassi became Europe’s first female professor.

Appointed by the University of Bologna in 1732 aged 21, she went on to win international acclaim for her experimental work on electricity, become her institution’s highest-earning academic and establish herself as an influential political figure in 18th-century Italy. She also gave birth to 10 children during a stellar 45-year scientific career.

But what was the impact of groundbreaking figures such as Bassi and 18th-century maths professor Maria Agnesi, also a Bologna graduate? Did they contribute to a wider acceptance of women’s role in Europe’s academy that endures today?

Some scholars believe that the upper echelons of academia remain a largely all-male enclave, with recent efforts to promote more women to senior positions progressing at a painfully slow rate.

Only one in five professors is female across the European Union’s 28 states, despite making up 47 per cent of PhD graduates, according to the latest European Commission figures published last year.

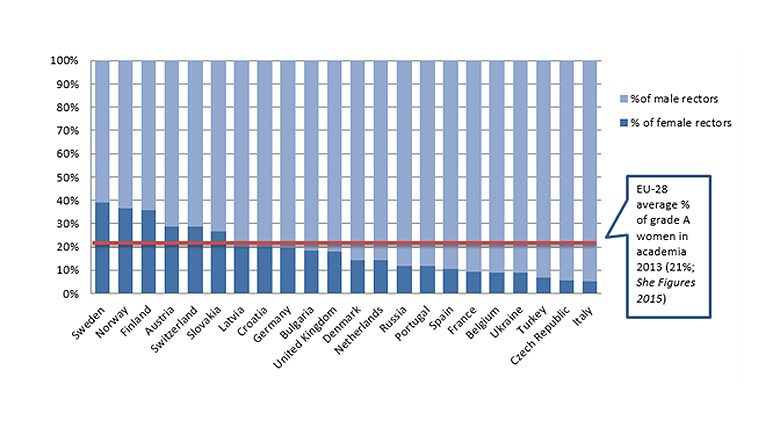

And only 15 per cent of European universities are led by women, according to a recent survey by the European University Association of its 850 member institutions, up from 11 per cent in 2014.

In many countries, including Italy, Belgium and France, the proportion is less than 10 per cent, the EUA says.

A larger survey by Women in Science, which covered about 2,500 higher education institutions across the EU, puts the proportion of female leaders slightly higher at 20 per cent.

“It was 12 to 13 per cent less than a decade ago, so the proportion is improving, but things are moving very slowly in many countries,” said Christina Ullenius, who was rector of Karlstad University, in Sweden, from 1995 to 2007, and is now a founder member of the European Women Rectors Association (EWORA), which held its first meeting in Brussels in June.

EWORA, whose board includes past and present female university leaders, is keen to create summer training schools for aspiring female rectors, as well as promote the wider benefits of a more diverse university workforce.

Male and female rectors per country (23 countries with female rectors)

Source: EUA

Mentoring and training for female academics were crucial parts of a five-year project, led by Professor Ullenius in the early 2000s, that was designed to increase the number of women in university leadership positions in Sweden.

“State reforms to address work-life balance began in Sweden in the 1960s, but towards the end of the 1990s there were only a few women leading universities,” she said.

“The proportion of women leaders was about 10 per cent when we started, but had doubled by the end of the project,” she added, saying that the current ratio was now approaching 50:50.

“Women are now succeeding women as heads of institutions – as I was at Karlstad – which shows it is quite normal to have a female vice-chancellor,” Professor Ullenius said.

However, she believed that many sectors need “more severe measures” of gender quotas and targets in addition to the peer support offered by mentoring and other initiatives.

“It is not the ideal way to solve this problem, but these measures can be useful,” Professor Ullenius said.

“When the Swedish government asked for at least 20 per cent of professors to be women, our system was totally shaken [up], but they found the women fairly easily to fill these posts,” she added.

More countries are now set to follow Sweden’s example, with the Republic of Ireland, which has never had a female university president, likely to set gender equality targets for its higher education institutions after the recommendations of an independent review announced in June.

Addressing the relative lack of diversity in elite university leadership positions is likely to have positive effects for the whole sector, “normalising” the practice, Professor Ullenius believed.

“I used to think that having a female university leader would make little difference, but so many people told me that it was important to have a role model,” she explained.

“If you only see men in leadership roles, it is difficult to imagine yourself in that position."

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Network aims to help more women reach top in Europe

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?