Soaring investment returns and improved international education earnings prevented a large group of Australian universities from plunging deeper into deficit last year, financial accounts have revealed.

But with the investment windfalls monopolised by a handful of rich institutions, a wealth gap within the sector is widening. And with international education income jeopardised by the federal government’s heavy-handed treatment of student visas, the future of some universities appears bleak.

More than half of Australia’s universities have now published their annual reports, offering a guide to the sector’s recent financial health. Of the 20 institutions – primarily the public universities in Queensland, Victoria and Western Australia – 10 registered surpluses in 2023, up from four in 2022.

Collectively, the 20 institutions converted a A$1.1 billion (£576 million) deficit into a A$427 million surplus. But this A$1.5 billion reversal of fortune owed much to a A$1.1 billion increase in international tuition fee revenue, and more to a A$2 billion turnaround in investment returns.

The investment successes might not last, given the wildly fluctuating markets of recent years. And with vice-chancellors warning that visa policy upheaval will cost universities hundreds of millions of dollars, the recovery in international earnings appears temporary.

“Things are looking pretty negative, except for maybe a few of the Group of Eight [members] whose international [numbers] are still healthy,” said Andrew Norton, professor in the practice of higher education policy at the Australian National University.

Professor Norton said many institutions had awarded their staff above-inflation wage increases in a “catch-up from the Covid period” that would increase their costs, as would new rules around the employment of casual and fixed-term staff.

He said mounting workload obligations associated with Universities Accord reforms, such as student support policies and sexual assault reporting requirements, were “adding costs without any revenue”.

Meanwhile, earnings remained depressed, with universities this year forecasting lower receipts from Fee-Help – the main loan scheme for unsubsidised students, typically postgraduates. “The only positive thing on the horizon is some demographic recovery in the school-leaver market. Apart from that it’s looking pretty bad, I think, for coming years.”

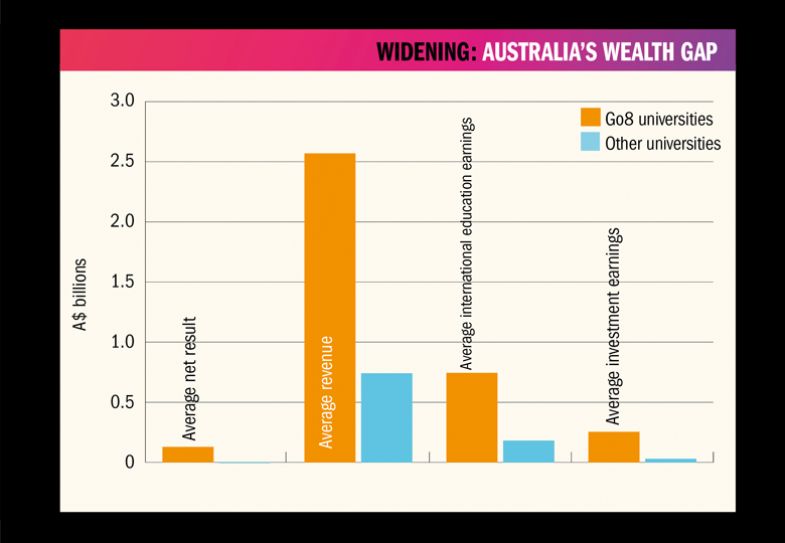

Things look relatively good for the research-intensive Group of Eight (Go8) universities. The four members that have so far reported their financial accounts registered average surpluses of almost A$130 million last year, with the other 16 institutions posting average deficits of A$5 million.

Combined international education and investment earnings for the four Go8 members averaged about A$1 billion each, compared with A$210 million for the other 16.

The research-intensive universities’ rankings allure and hefty investments helped shield them from the failure of government funding to keep pace with costs. Federal funding rose by just 2 per cent across the 20 institutions, while their outlays on staff rose by 11 per cent.

Meanwhile, income from domestic students declined across the 20 institutions, with teaching subsidies down by 2 per cent and tuition fee loan revenue by 7 per cent.

While domestic enrolments have slumped in recent years, former La Trobe University vice-chancellor John Dewar said “under-loading” was also having a financial impact. Professor Dewar, now a partner with advisory firm KordaMentha, said students were going part-time as their living costs rose.

“You’re dealing with the same headcount but you’re getting less revenue,” he told a Sydney round table organised by edtech company TechnologyOne. “Those students need the same support, no matter what load they’re carrying. Their demand for services is not decreasing.”

Professor Norton warned that there were no “obvious” solutions to universities’ fiscal troubles. “I think some of the solutions of the past, like more international [students] or higher student contributions, are no longer feasible and therefore the options are limited.”

The universities of Melbourne, Monash and Queensland posted surpluses well over A$100 million each, mainly thanks to investment yield turnarounds that exceeded A$300 million at Monash and A$450 million at Melbourne and Queensland.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?