Source: Chris Draper

Sometimes the devotion to a deceased individual eclipses a clear vision of what materials would be genuinely useful in future research

There is a striking short story by the American novelist Edith Wharton about the afterlife of a great philosopher called Orestes Anson.

His house becomes a place of pilgrimage for admirers of his work. His granddaughter Paulina takes on the role of “guardian of the family temple”, to whom “critics applied…to verify some doubtful citation or to decide some disputed point in chronology”. She passes up the chance of personal happiness, produces a major biography of her grandfather and delivers it to a publisher, only to be told “We ought to have had this 10 years sooner…Literature’s like a big railway station now, you know: there’s a train starting every minute. People are not going to hang round the waiting room.”

Reflecting on this afterwards, Paulina realises that fewer and fewer people have been coming to Anson House to look at her grandfather’s papers and she is overcome by a “sense of wasted labor…There was a dreary parallel between [his] fruitless toil and her own unprofitable sacrifice. Each in turn had kept vigil by a corpse.”

Although The Angel at the Grave doesn’t end on quite such a melancholy note – a young man comes seeking a copy of a long-forgotten pamphlet that he believes to be Anson’s masterpiece – it offers a vivid illustration of some of the key issues around academic archives and legacies.

How far are such records of works in progress or abandoned worth preserving? Should academics try to put them in order for the use of future scholars – and who is to say what will prove most interesting? If they never get round to doing this themselves, should spouses or children become “guardians of the family temple”, classifying the material they inherit, donating it to academic libraries, seeking possible publishers or even completing unfinished projects? And can’t this turn into a trap, with bereaved relatives putting their own lives on hold as they devote themselves to preserving the memory of a dead ancestor that everybody else has forgotten about?

Sarah Shoemaker, associate university librarian for archives and special collections at Brandeis University in the US, encourages “academics looking to donate papers…to find the appropriate archive and begin a conversation with the archivists…we like to work with living scholars, and even in some cases scholars who have not yet retired”, since that enables them to “ask questions about materials that come to us en masse”.

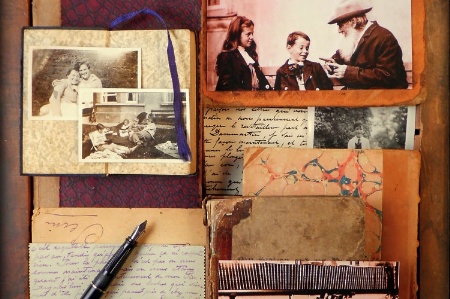

As for how these should be presented, Shoemaker notes that archivists often “look to the principle of original order; the order in which papers were kept by their creator can reveal context in an interesting way”. They are also happy to carry out any necessary weeding, which can be “a sensitive subject with the creators of collections and (particularly) their heirs”. In the case of a family member, she adds diplomatically, “sometimes the devotion to a deceased individual eclipses a clear vision of what materials would be genuinely useful in future research”.

One leading architectural historian with a substantial collection of drawings and photographs as well as books (who asks to remain anonymous) would like to keep much of his material together, if at all possible. “I have expressed certain views to my literary executors about setting up a trust so that it can be made available for specialist study. I am reluctant to give it to institutions because I have wonderful things on my shelves which have been chucked out from supposedly respectable university libraries,” he explains.

“I plan to issue fairly detailed instructions, giving as much guidance as I can without imposing a huge burden on my heirs and allowing them freedom of action. I have also nominated people from whom advice might be sought.”

Another academic in her mid-seventies has been less proactive in putting her papers in order.

Ursula King, emeritus professor of theology and religious studies at the University of Bristol, admits to a “magpie mentality”, which probably goes back to a childhood in wartime Germany where “every shoelace would come in useful”. A colleague once suggested to her that research students come in two kinds: those who “collect too much and have to be restrained, as if in a jungle” and those more like a desert that “you have to water constantly”. The same was true of writing: “I always collect too much material and then need to cut back – which means I am left with lots of material afterwards.” Although King acknowledges that “there is something to be said for throwing everything away after a book is written”, she herself tends to preserve the notes and drafts and proofs. She has reduced her large library by a third but still refers to the remainder.

Along with material relating to completed projects, King has kept “plans for books where I have done most of the research but never found the time to write it all up” and says it is now “very difficult to find my way through these mountains of papers…It is unclear whether I want to put some of this material together for writing some more books, extract the most valuable insights and do something new with them or follow the advice of some of my friends to write a memoir…”

A long-term interest in the French Jesuit palaeontologist and mystic, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, whom King has written several books about, has generated a significant archive. She has already confirmed that the specialist collection at Georgetown University is happy to take this. But what about the “too many files, too many books and too many notes” she has built up over the years in areas such as spirituality, feminist theology, and religion and gender?

Although unable to follow the example of a friend who “just put it all in sacks and out in the bin”, King acknowledges that “my daughters are not interested in the material and may throw it out. Some of it is not of long-lasting substance – we have to be humble about what we have done.”

And what of the children who have to deal with their parents’ academic papers? Heirs controlling the estate of a really well-known writer, composer or artist, whose every doodle (and practically every nail clipping) is valuable, can find it a full-time job to deal with copyright issues, assist or obstruct researchers, and protect his or her image. But it can also be a significant source of income. Few, if any, academics fall into this category (unless they happen to have written The Lord of the Rings or the Narnia novels on the side). So how can their children find the right balance between throwing everything in the dustbin and the kind of “wasted labor” Paulina Anson later regretted?

Robin Feuer Miller, professor of Russian and comparative literature and Edytha Macy Gross professor of humanities at Brandeis University, inherited material from two academic parents.

Her father, Lewis Feuer (1912-2002), was a leading intellectual historian who moved across the political spectrum from left to right and then, to some extent, back again. When he died, she recalls, he left his house in a state of “complete and utter chaos…There were books and papers everywhere, in the basement, in all the bathrooms, in the attic, piles on the floor, pamphlets from the 1930s…” Archivists at Brandeis, who agreed to take it all, “spent a summer sitting on the floor in this hot, unairconditioned house going through things. And many of the papers they would really like to have taken, they couldn’t, because there was mould on them.”

Lewis’ major unfinished project, his daughter recalls, was “a tremendous multi-volume biography of John Dewey, and in the early days his publisher wanted to bring it out volume by volume. My father stupidly said ‘no’ and had almost finished it when Alzheimer’s intervened.” Although Miller realised that she “could spend the next 10 years of my life trying to find out about John Dewey” in order to complete the book, she has consciously avoided Paulina Anson’s trap and decided “not to go near it”.

In the case of her mother, fellow Russian scholar Kathryn Beliveau Feuer (1926-92), Miller took a different line when she inherited a dissertation about Tolstoy’s successive manuscripts of War and Peace. This had largely been researched when the family spent the year 1963 in the Soviet Union, “a very tense time after the Cuban Missile Crisis”. The experience proved traumatic. Kathryn managed to smuggle out of the country Anna Akhmatova’s now classic anti-Stalinist poem Requiem, which led to the “terrible ordeal of the whole family being arrested at gunpoint” – and so, after completing the dissertation, Kathryn filed it away without publishing it, determined never to revisit such a painful period of her life.

Archivists spent a summer in this hot, unairconditioned house. Papers they would like to have taken, they couldn’t, because there was mould on them

After her mother’s death, publishers urged Miller to go back to the dissertation. Kathryn was a rare example of a Western scholar who had done in-depth research within Russian literary archives and they knew it would be of great interest to those studying Tolstoy. Her daughter therefore decided to join forces with her colleague Donna Tussing Orwin to work on what became Tolstoy and the Genesis of War and Peace.

This took them a year and a half. While the result, published in 1996, was essentially Kathryn’s research adapted for a wider readership, Miller had to “work through the manuscript sentence by sentence by sentence. I worked on the prose and in some cases the organisation. It was a generational moment, because I was basking in the joy of hearing her voice again, but I was also editing it.” This may sound like a rather self-effacing task, but she became uncomfortable when the book went on to garner great reviews and a prize, and she found herself delighting in “the glory of something my mother had decided not to publish. I felt guilty and selfish more than selfless.”

Strangely enough, however, Miller also found unexpected treasure among her father’s papers, namely “45 years’ worth of letters from a woman in Japan” – a woman her father had known before the Second World War. “They had been deeply in love…[but] she had to go back to Japan and he went off to fight. She became quite somebody in Japan and, for much of her life, remained in love with him and wrote these letters. Each vowed to destroy the other’s letters when they got old, but he never did.”

Although Miller had known of the woman’s existence, she was astonished to discover that she had maintained such a “lengthy, intimate and intellectually engaged correspondence” with her father. As she worked through it, Miller “responded deeply and found I have things to say to her, as a woman across decades and decades, as a daughter of the man she loved, as an American woman facing a Japanese woman”. She remains unsure whether she will produce “an odd little book”, drawing on someone else’s story to write about her own preoccupations, or perhaps even a novel.

Another child of a leading academic agreed to take on a parental project, little knowing how long it would take, yet still found a way to make it her own.

Karen Avrich describes herself as “a writer and editor with a background in history”. Her father Paul Avrich (1931-2006), a professor of Russian history, had “a scholarly passion for the anarchist movement”. During the course of his career, he wrote a number of books on the topic and spent decades locating, interviewing and befriending anarchists who had been active in the early to mid 20th century. “He recorded their stories, collected their letters and photographs, and chronicled their experiences,” Karen explains. “Many of these men and women, in recounting their memories, showered admiration upon the brilliant, volatile Alexander Berkman (Sasha), a leader of the movement…[who] achieved notoriety when he attempted to assassinate the industrialist Henry Clay Frick.

“My father was captivated by Berkman and the cinematic contours of his life, and hoped to one day tackle a dual biography of Berkman and Emma Goldman, the iconic radical whose intimate friendship with Sasha endured for 50 years.”

In the 1990s, however, Paul became ill and asked his daughter to complete what eventually became Sasha and Emma: The Anarchist Odyssey of Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman. She was “keen to help in any way I could, although I was scarcely aware of the vast scope of the project”. While the fundamental research had already been done, Karen did a great deal of reading and travelling to “discover new material and information” for herself, and remembers other “assignments of interest to me that I turned down”. But during the six years it took before the book was published in 2012, she found herself “as engaged with the stories and the characters as my father had been” and began to realise it was hers as much as his.

It proved impossible, for example, just “to pick up where he left off” or to adopt his style, and she felt “a little less forgiving about some of the crimes”. She also felt that Emma deserved equal billing with Sasha. In such ways, the book became a satisfying personal project, rather than just a burden undertaken out of duty, while remaining “a strange but inspiring way to connect with my father after his death”.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?