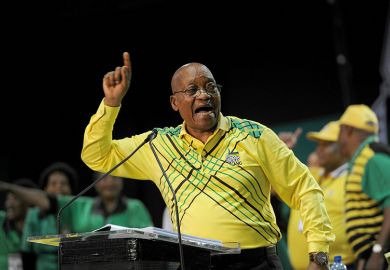

Any thought that the resignation of Jacob Zuma as South African president might result in the scrapping of his new fees policy was laid to rest in the country’s budget, presented on 21 February. This confirmed that higher and further education students from low-income families would no longer pay tuition fees.

The launch of the new fees policy has been messy. Zuma announced it in December, against the advice of his own feasibility commission, in a populist gesture that had no grounding in government policy. South Africa’s bellicose opposition party, the Economic Freedom Fighters, encouraged prospective students from poor households to demand admission, whether or not they had applied; universities predicted chaos and anarchy. But incoming president Cyril Ramaphosa was quick to acknowledge the commitment, and his first budget set aside R57 billion (£3.5 billion), to escalate by 13.7 per cent per annum until all years of study are covered. This has necessitated significant cuts to other areas of state spending.

Qualifying students already at colleges and universities will have their loans converted to bursaries. But although the new academic year is now under way, and a large number of registered students are awaiting the outcome of their applications for fee exemptions, practical details of the new system remain sketchy. There could be significant implications for higher education and training as a whole that have yet to be considered. The slow revolution across South African campuses, which began three years ago this month, is set to continue.

Universities South Africa, which represents all 26 public universities in the country, has welcomed the new policy. While critical of the lack of planning, its chief executive, Ahmed Bawa, sees the policy as a powerful new initiative to address the needs of a large number of students and their families. Inequality in South Africa is among the highest in the world. Given the high – and rising – levels of university fees, households bringing in less than R600,000 (£36,400) a year are now unable to support a single student at a public university. To put this in context, the average annual salaries of registered nurses and high school teachers are R211,000 and R191,000, respectively. The new policy will cover full tuition fees for families earning less than R350,000; those with between R350,000 and R600,000 may be spared fee increases in 2018.

Just over 1 million students were enrolled in public universities in 2017, with about 194,000 starting for the first time. About a quarter were supported under the terms of the previous policy, which had an income threshold of less than half the new one. In January, the Department of Higher Education and Training announced that more than 300,000 applications for financial support had been received for the 2018 academic year.

Initial briefings from Universities South Africa indicate that the cost of tuition for qualifying students will be fully funded to the levels set by their universities. This is significant because South Africa currently has no statutory restrictions on fees and they vary by university and discipline. Hence, it is likely that the government will now impose fee caps. For elite universities such as the universities of Cape Town and the Witwatersrand that rely on annual above-inflation fee increases, such limits will have significant consequences.

A more general problem is that there is no coherent policy for South African education as a whole. A large number of people with the potential to succeed at university do not have access to schools that can prepare them adequately for the National Senior Certificate that they need to apply for a place. While education is a right specified in the constitution, inequities in access begin in the earliest years, with low levels of functional literacy in primary schooling.

These and other policy failures are a consequence of the general paralysis and controversy of Zuma’s presidency. But Ramaphosa’s appointment of Naledi Pandor as minister of higher education is good news; Pandor, the former minister of science and technology, is widely respected for her experience and commitment.

With strong leadership, Zuma’s populist gesture can be converted into the keystone for a progressive set of policies that could mitigate South Africa’s long and continuing higher education crisis.

Martin Hall is emeritus professor at the University of Cape Town.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Fees must still fall

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?