When Lydia Royce went on maternity leave last year, her student debt was the least of her concerns. But after national conversations suddenly erupted last month over England and Wales’ student loan system, Royce decided to check her balance. She was horrified to discover that despite having taken voluntary redundancy during her maternity leave – and, therefore, earning less over the course of the year than the repayment threshold – her loan debt had risen by £1,900, even as she struggled to make ends meet on statutory maternity payments that didn’t even cover her mortgage, let alone her living costs.

“It just highlights how ridiculous the interest being added to it is, doesn’t it?,” she told Times Higher Education.

The UK’s newspaper columns, airwaves and social media have been flooded in recent weeks by politicians, journalists and campaigners debating the merits of the so-called Plan 2 tuition fee system introduced in 2012, when the tuition fee cap nearly trebled in England from £3,225 to £9,000 per year. In the same year, it rose in Wales from £1,175 to £3,465 for Welsh-domiciled students – or £9,000 for those from elsewhere in the UK; in 2018, fees for Welsh-domiciled students were also raised to a maximum of £9,000, but with grants offered to offset the cost for students from a lower-income background.

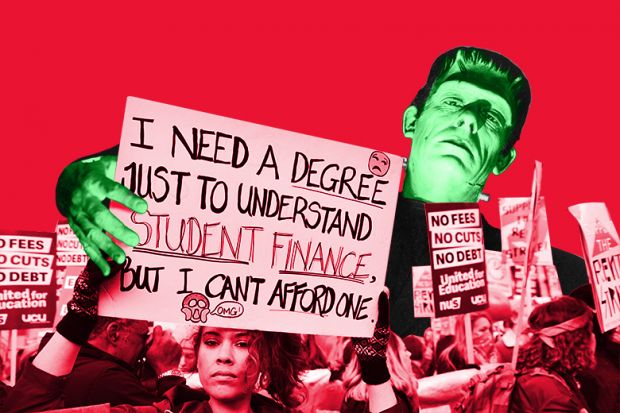

One Labour MP, Luke Charters, told Parliament last month that the tuition fee system has become a “Frankenstein’s monster”. He said the repayment terms for Plan 2 loans – which see students repay 9 per cent of their earnings above a £28,470 threshold – are “needlessly complex”. He added that they are “riddled with ludicrous features, like charging higher interest rates to those who could go on to earn more” – referring to the interest rate of 3 per cent plus RPI charged to graduates earning more than £51,245 (those earning less than that are only charged RPI after they leave university).

“Plan 2 borrowers, including me, were actually never clearly told that the higher graduate earnings mean higher loan interest,” Charters said. “As a former FCA [Financial Conduct Authority] regulator, even though the [FCA] regulations don’t apply to student loans, let me tell you that in my honest view, the communication around student loan repayments, where income is linked to interest rates, feels like a sort of mis-selling scandal waiting to unfold,” he said.

Charters is one of an emerging cohort of millennial politicians who are repaying Plan 2 loans. With the help of similarly aged colleagues in the media, they are forcing back on to the political agenda an issue that many observers assumed had been settled. Chancellor Rachel Reeves’ decision in her 2025 autumn budget to freeze the student loan repayment threshold for the next three years in England appears to have been the spark for a reconsideration of the whole concept of student loans in the UK – even though the Welsh government has said it will not freeze the repayment threshold and students in Northern Ireland still take out “Plan 1” loans, whose interest rate is the lower of RPI or the Bank of England base rate plus 1 per cent.

Amid a funding crisis and increasing scepticism about the value of a degree, many UK universities will no doubt be nervous about the effect the debate may have on university applications in the months and years to come.

With annual tuition fees now at £9,535, students in England now graduate on average with £53,000 of debt. Interest is charged the moment the loan is taken out and, as Royce’s story highlights, continues to accrue even if graduates lose their job, take sick leave or go on maternity leave. As a result, two-thirds of British graduates accrued more interest than they repaid in the 2024-25 tax year, according to an investigation by The Times. Overall, £15.2 billion of interest was added to student loans last year, while only £5 billion was repaid.

Graduates with Plan 2 loans earning £100,000 have a marginal tax rate of about 69 per cent. This is even higher if they have a postgraduate loan, which is charged at 6 per cent of earnings above £21,000 – a threshold that has not increased in a decade despite high inflation and stagnating wages during that period.

But the architects of the system continue to insist that it is fair. Speaking in 2010, David Willetts, the minister for universities and science at the time, said the UK’s higher education system had “many strengths” but needed a greater focus on the student experience, widening access and sustained funding. In a statement to the House of Commons, he said that replacing teaching grants almost entirely with student loans offered a “thriving future for universities, with extra freedoms and less bureaucracy, and they ensure value for money and real choice for learners”.

Willetts declined to be interviewed for this article but he has consistently defended the student loans system as the only realistic way to fund a massified higher education system. And in a recent blog post, Willetts’ then special adviser, Nick Hillman, argued that Plan 2 loans’ above-inflation interest rate for the highest earners was their “single most progressive feature” since it “ensures better-off graduates do not extinguish their loan swiftly and instead go on paying back for longer”.

Hillman, who is now director of the Higher Education Policy Institute, added: “As the arguments rage, let’s not pretend the new campaign is anything other than what it is: an attack on the most progressive feature of England’s (old) student loan system by those whose degrees have helped them on to higher-than-average wages,” he wrote.

The parenthetical “old” refers to the fact that Plan 2 loans were replaced for new borrowers in England in 2023 by Plan 5 loans, which only charge interest in line with RPI. Hillman said that the media coverage of the issue has seemed irresponsible because it implies to people currently holding offers from universities that higher education is not worth it – also ignoring the earnings premium that a degree typically offers.

But Aaron Porter, who was the president of the National Union of Students (NUS) in 2010, when the tripling of tuition fees was announced, told Times Higher Education that the Plan 2 loans have been a “ticking time bomb” ever since they were introduced – amid mass protests from students.

“Frankly, I’m surprised it’s taken this long for there to be both public and political recognition of the scale of the problem of the student loan system,” said Porter, who has subsequently held a range of university board and advisory roles.

In his view, universities gave up their teaching grants “too easily” and “turned a blind eye” to the impact this would have on students: They “never fully appreciated that universities themselves would be questioned about value for money in a much more vociferous way than they had been previously”.

Porter’s biggest concern at the time was that the reforms “fundamentally altered the compact between the state, the individual and universities” about how higher education should be funded: “I sat in meetings where vice-chancellors offered up the teaching grant in exchange for higher tuition fees, and they were so short-sighted in not seeing how that would eventually come back to bite them.”

The NUS’ current vice-president for higher education, Alex Stanley, also considers it “not surprising” that the issue has shot back to the top of the political agenda 15 years on given that there are now 4.1 million graduates on Plan 2 loans, many of whom are struggling to get on the housing ladder and start a family because of the cost-of-living crisis. Moreover, England’s freezing of the repayment thresholds for Plan 2 loans at £29,385 for three years from April means that an already “absolutely brutal system” is “only getting worse”, Stanley said: “I think it’s got to the point where people are fed up.”

Even Martin Lewis, the high-profile consumer finance expert who is generally positive about the wisdom of taking out income-contingent student loans, has lambasted the threshold freeze as a “breach of natural justice” and a “stealth tax”. He added that graduates who attended university between 2012 and 2015 should feel especially aggrieved by government policy, as, during that period, the government had explicitly promised to increase the threshold in line with average earnings, which has not happened. Speaking on the BBC’s Newsnight programme, he said that “unilaterally changing the terms” of the loan in this way “would not be allowed for any commercial lender: it would go against all forms of consumer law. It’s a breach of contract, and it’s a breach of promise.”

In his most recent blog on the topic, Hillman complained that the debate of student loans drags on despite no one being able to agree on the precise problem – or its solution. “I think the current conversation reveals something important: people know they don’t like the system we have but seemingly have no real idea of what a big reform to it would look like,” he wrote. “Perhaps the widespread anger among younger graduates really stems from a wider sense of intergenerational inequity.

Nor are Hillman and Willetts the only architects of the current system to continue to insist that any problems with it come down to the details of repayment terms, rather than with the wider concept of income-contingent student loans. Bruce Chapman, who designed the first such system, implemented in Australia in 1989, told Times Higher Education that income-contingent loans remain the fairest form of university funding.

Under these systems, also used in New Zealand and Hungary, “everyone can enrol and pay nothing upfront”, he said, erecting no participation barriers for poorer students, while repayments only begin above an earnings threshold, account for the same amount per month regardless of debt levels, and are written off after a fixed period. By contrast, under the US’ “mortgage-style” student lending system, defaulting on loans is possible, and this “ruins people’s credit reputations”.

Moreover, the default rate is “extraordinary”, Chapman said, reaching 60 per cent in Thailand, 50 per cent in Colombia and “at least” 20 per cent in the US, where roughly 12 million defaulters can’t get a loan for other purposes because they’re seen by the bank as “too risky”.

“Even though, in my view, English debts are too high, and the interest rates are wrong, you’ve still got the essence right,” Chapman said. “Most people don’t come to that conclusion because they don’t understand the alternative.”

But the NUS’ Stanley argued that it would be “a real mistake” for the UK government to “ignore” student loan debt, and he criticised chancellor Rachel Reeves for recently describing the current system as “fair and reasonable”.

“It’s incredibly frustrating hearing that from a set of politicians who either paid very low tuition fees or no tuition fees and [from] politicians who had access to maintenance grants alongside that, meaning their debt burden was even lower,” he said.

One Labour MP, who asked not to be named, believes student loan dissatisfaction is an issue the Labour government could lead on – provided that it takes decisive action. They said the government “can draw lessons internationally”, describing as “transformative” Australian Labor’s successful election pledge last year to cut 20 per cent from graduates’ loan debt.

Chapman, who is emeritus professor of economics at the Australian National University, also had “no doubt that this affected voting behaviour” despite not itself offering any relief to graduates for “many, many years” because the cut will shorten repayment periods rather than lower monthly repayment levels (although the repayment threshold has also been raised from A$54,000 (£28,000) to A$67,000, which is expected to save the average debt holder about A$680 a year).

This suggests, Chapman said, that there is a “psychological” impact of talk of loan debt that economists, including himself, assumed would not apply if repayment was income-contingent – terms that many argue make it resemble a tax more than a commercial loan. “People don’t like debt,” he noted.

On that score, it is worth noting that Labor leader Anthony Albanese is far from the only politician to derive apparent electoral mileage from pledges to reduce student debt. Such a promise was a big plank of Joe Biden’s successful bid for the US presidency in 2020. Jacinda Arden swept into power in New Zealand in 2017 on a pledge to abolish tuition fees – scaled back, once she attained office, to only the first year of fees, recently switched to the final year. And in the same year, Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party received 61.5 per cent of the vote from the under-forties in the UK’s general election after promising to abolish tuition fees – a result, popularly described as a “youthquake”, that nearly saw him score an unlikely victory and spooked then prime minister Theresa May into launching a review of fees that ultimately recommended a cap of £7,500 in 2019 – but which was never implemented by her successor, Boris Johnson.

Corbyn’s commitment has recently been echoed by Green Party leader Zack Polanski, who believes there should be a national conversation around student debt forgiveness. His party is currently the most popular with the under-fifties, according to polls.

However, many commentators argue that the vast cost to the public purse of writing off student debt and replacing tuition fees with teaching grants is not justified by the equity gains, particularly given the opportunity cost of denying funding to other areas of public spending, such as schools and hospitals.

Currently, almost £21 billion per year is loaned to about 1.5 million students in England. Outstanding loan balances in England at the end of March 2025 totalled £267 billion, forecast to reach around £500 billion by the late 2040s. Concerns about low repayment rates drove the replacement of Plan 2 loans in England, so while Plan 5 loans only charge interest in line with RPI, the repayment period has been extended from 30 to 40 years and the repayment threshold lowered from the current £28,470 for Plan 2 loans to £25,000.

The political wisdom of covering all that debt out of general taxation is all the more fraught at a time when the value of a degree, in terms of preparing graduates for success in the job market, is increasingly being questioned, commentators suggest. One such sceptic is Paul Wiltshire, a retired statistician who has calculated that for many students with lower prior academic attainment, the graduate premium is negligible at best. He argues that “mass” higher education is “exploitative” as it has created a system where employers “discriminate“ against non-graduates, while many graduates are left with large debts that they can’t pay off – creating a “student debt trap” that is “demoralising the nation”. He advocates turning back the clock, capping university attendance at 15-20 per cent of the population and only then reintroducing public subsidies for tuition costs.

Unsurprisingly, the NUS does not endorse a downsizing of higher education. Rather, the union is calling on the government to abolish the freeze to repayment threshold (which also applies to Plan 5 loans), cut the rate of interest and introduce a lifetime cap on the total interest graduates pay. Indexing interest to RPI should also be re-examined, according to Stanley; given that this is typically higher than other measures of inflation, such as the consumer price index (CPI).

Despite Willetts’ and Hillman’s efforts to ensure that wealthy students pay more via the Plan 2 loans’ real rate of interest, Stanley notes that the wealthiest students are still able to bypass interest payments entirely by paying the full fee amount upfront. For that reason, Porter believes a levy should be considered for students who do so – “probably less” than the total interest paid over the 30-year repayment period, but a lot more than zero. The Plan 2 interest rate is “simultaneously the biggest driver [of] and barrier to…a more progressive system”, Porter said.

However, he argued that while such “piecemeal” changes to Plan 2 loans may make “modest improvements around the edges”, they won’t “really do justice to the scale of the problem”. He believes there needs to be conversations around reintroducing teaching grants and addressing the “high degree of volatility” in the university funding system caused by the removal of student number caps.

The current student loan system is one that “students, graduates and the Treasury all think is a bad system. That screams to me that it is a system that has singularly met its expiry date and needs to be fundamentally re-examined,” said Porter.

The conversation around Plan 2 debt is not just abstract – it has real influence on young people’s decisions – and, by extension, the country’s economic health. Stanley argued, for instance, that some graduates might turn down promotions rather than tip themselves into the higher marginal tax bracket of, currently, 6.2 per cent, amounting to a price on “aspiration”.

And some graduates may decide to stay out of the employment market entirely. Royce, who was originally due to be returning from maternity leave in March before she took voluntary redundancy, has been weighing up whether and how to return to the workplace. She concluded that it was not worth it to return full-time given the childcare costs for two young children, a mortgage and, on top of that, £200 monthly repayments on her undergraduate and postgraduate debt. Instead, therefore, she has chosen to work only part-time to keep childcare costs down.

“For some people, £200 is not a lot of money,” she said, but if she hadn’t had to pay them, “The deductions in my student loan would have covered around half of my childcare bill” for a four-day week.

Stanley’s advice to graduates experiencing the malaise? “Keep kicking up a fuss,” he said.

“I have not seen any conversation about graduate debt as large as this, and it all comes as a result of the fact that we are really being impacted. Those of us on Plan 2 are seeing our debt spiralling. We’re feeling the pinch. We’re not able to invest in our futures. And if we continue to put this pressure on, I can see the government changing their mind on this.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?